Spanish Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico

Spanish Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico

The Discovery of the Americas, 1492-1518

On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus spotted an island in the Bahamas while searching for a westward route from Europe to the East Indies. Though he was not the first European to discover the Americas, it was Columbus' discovery that launched an age of vigorous exploration of the New World. Columbus - an Italian sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain - made a total of four voyages to the New World from 1492 to 1502, visiting the Caribbean, Venezuela, and Central America in his attempt to find a westward passage to the Indian Sea. On all four voyages, he visited the island of Hispañola. It was here, in 1496, that the first permanent European settlement in the New World was founded - Santo Domingo in the present-day Dominican Republic.

Santo Domingo was Spain's foothold in the Americas, the place from which it launched fleets to expand its empire. Juan Ponce de León settled Puerto Rico in 1509. Juan de Esquivel conquered present-day Jamaica in 1510. Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar conquered Cuba in 1511. In 1513, Ponce de León discovered Florida, which he assumed to be another island in the Caribbean Sea.

Christopher Columbus, Ponce de León, Juan de Esquivel, and Diego Velázquez were four of the first conquistadors - men who were granted authority by the Spanish crown to explore and settle a certain part of the New World. Conquistadors hoped to find territories that were rich in gold, silver, or gems, or ones that could be made profitable by other means, such as enslaving the native populations to produce cash crops. The Spanish crown recognized conquistadors as the governors of the territories they conquered, and allowed them wide latitude as to how they governed and how they used their profits, after taking out the king's share. The main thing expected of the conquistadors, after loyalty and tribute to the crown, was to uphold the doctrines and institutions of the Roman Catholic church and to encourage the natives to convert to Catholicism. Typically, the crown supplied little of its own funds; instead, the conquistador was expected to raise his own army and purchase and provision his own ships.

Most of the men who joined the conquistadors' expeditions were soldiers and noblemen who had ambitions of wealth and power. Most of them had to not only pay a fee to the conquistador to help him cover his costs, but they also had to pay for their own armor, weapons, and food, and whatever else they needed.

With so much of each conquistador's fortune and future at stake, it did not take long for bitter rivalries to erupt in the New World. Each representative of the Spanish crown sought to enlarge his own territory and income at the expense of the others, using whatever legal, political, economic, or even military means that were at his disposal. Christopher Columbus spent the last years of his life fighting to retain control over the territories he discovered. His son, Diego Colón, spent most of his adult life defending these claims and defending his title as Viceroy of the West Indies. Colón's biggest problem - beside enemies in the royal court in Castile - was Diego Velázquez, who was seeking to establish his own power base out of Cuba.

By 1516, both Ferdinand and Isabella had died. Their grandson, Charles, succeeded to the throne of Spain. King Charles I enthusiastically pursued and expanded his predecessors' program of exploring, colonizing, and conquering the New World.

In 1517, Velázquez authorized Francisco Hernández de Córdoba to explore the seas west of Cuba, where another ship had reported land. Hernández landed on the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico. He and his men were driven back by an army of Mayans, who were a much more advanced civilization than any native population that Spain had previously encountered. Hernández' expedition, though unsuccessful, proved to Velázquez that the lands to his west were worth conquering. An expedition authorized by Velázquez in 1518 skirted the coast of Mexico as far north as present-day Tampico and made contact with the Aztecs. Also in 1518, in an important power shift, Velázquez succeeded in severing Cuba from Diego Colón's jurisdiction and obtained royal recognition as the Governor-General of Cuba, subordinate only to King Charles himself.

Pineda Maps the Gulf of Mexico, 1519

At the beginning of 1519, Spain had settled much of the Caribbean and had explored parts of the Gulf of Mexico around Florida and southern Mexico, but the rest of the Gulf of Mexico had not yet been explored or mapped. At that time, Spain still had no idea that Florida and Mexico were part of the same large landmass. With Colón's influence on the decline, Francisco de Garay, who succeeded Esquivel as the governor of Jamaica - or Santiago, as it was known at that time - set his sights on this unclaimed area. Garay authorized Alonso Álvarez de Pineda to explore the area of the Gulf of Mexico between the Florida peninsula, which was under Ponce De León's jurisdiction, and southern Mexico, which was under Diego Velázquez's. The stated purpose of the expedition was to find the passage to the Pacific Ocean that was still assumed to exist.

Pineda embarked from Jamaica in March 1519. After crossing the Yucatan Channel, which separates Cuba from the mainland, he sailed north, reaching the panhandle of Florida. Pineda then turned east and followed the east coast of the Florida peninsula, looking for a channel, for it was still believed that Florida was an island. Nearing the tip of Florida and finding no channel, Pineda turned the ships around and followed the great curve of the Gulf, skimming the shores of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. On or about June 2, 1519 on the Julian calendar - or June 12, 1519 on our modern Gregorian calendar - Pineda became the first European to discover the Mississippi River. He named it Río del Espíritu Santo, or "River of the Holy Spirit," because of its discovery on the feast day of the Holy Spirit, or Pentecost. Pineda then continued sailing the coasts of Louisiana and Texas. No records exist of any landings he might have made or features he might have named until he reached the area now known as Pánuco, near present-day Tampico, Mexico.

At the same time that Garay sent Pineda out, the ever-industrious Cuban Governor Velázquez sent his own man, a conquistador named Hernán Cortés, to establish a colony in Mexico. Pineda and Cortés' paths crossed in late July or early August 1519, when Pineda arrived at Cortés' new settlement at present-day Veracruz. Cortés had Pineda's landing party arrested, and Pineda withdrew to Pánuco. Sources differ as to whether Pineda stayed there or returned to Jamaica with his fleet.

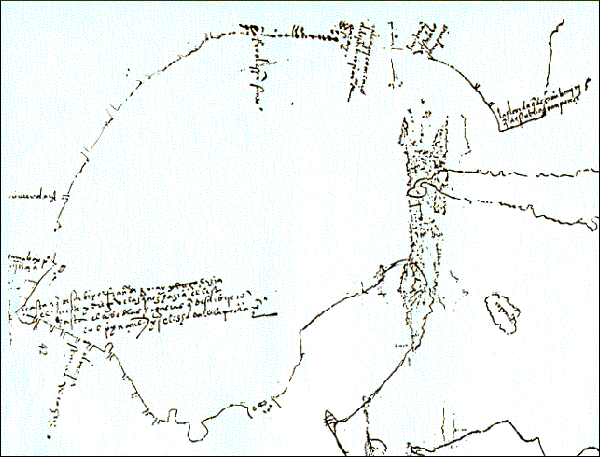

In either case, Governor Garay was presented a map of the area that Pineda visited. This simple line sketch, shown here on the right, is the earliest known representation of the entire Gulf of Mexico and is also the first known visual representation of any part of Texas. It portrays the Texas coastline as an arc that roughly represents the northwest quadrant of a circle. Near the top of the arc, to the west of the Rio del Espíritu Santo or Mississippi River, is a notch that probably represents the mouth of the Sabine River. Working west and south from there, the map shows three large bays of descending size, i.e. Galveston Bay, Matagorda Bay, and Corpus Christi Bay. South of there, it shows another notch that surely represents the mouth of the Rio Grande. The map does not show any barrier islands. The map does not show the prominent Mississippi River delta, and the proportions of the Florida peninsula are wrong (although the fleet may not have sailed the full length of it), but it does show two bays on the west coast, which would be Tampa Bay and Charlotte Harbor. Pineda's expedition proved that Florida is part of the mainland and also proved once and for all that there is no passage to the Pacific Ocean through the Gulf of Mexico.

The Gulf Coast Remains Unsettled, 1520-1527

Governor Garay quickly sent his report on Pineda's expedition to Spain. He also sent out another expedition in late 1519 or early 1520 to attempt to establish a colony in Pánuco, but the colony was destroyed by natives.

While Garay was working to establish a claim on the Gulf coast, Diego Velázquez was trying to maintain his. In a move ironically similar to the one Velázquez had made against Diego Colón, Cortes, shortly after his arrival on the mainland, declared himself the governor of his new province, independent of Velázquez's authority and subject only to the king of Spain. Velázquez responded by sending another man, Pánfilo de Narváez, to oust Cortés. Narváez, though more loyal than Cortés, was also less capable. Narváez had an overwhelming numerical superiority, but Cortés defeated him with little trouble. Narváez himself lost an eye in the fighting. He spent two years in Veracruz as Cortés' prisoner before being deported to Spain. By that time, Cortés had fully conquered the Aztecs and had given the name "New Spain" to the territory under his control. Velázquez did not attempt to remove Cortés by force again, but he did wage a legal battle against him. This ended with Velázquez's death in 1524.

Cortés thwarted Diego Velázquez's ambitions of ruling part of the North American mainland. Ponce de León had his hands full with trying to settle eastern Florida, much less expanding his reach. The other major player in the Caribbean, however, Francisco de Garay, still had plans. In 1521, after two years of waiting, Garay finally received a patent from King Charles I recognizing his authority over the territory from the cape of Florida to Cortés's New Spain.1 Garay called his territory Amichel, a name that was confirmed in the royal decree. While Garay's emphasis was on settling the Pánuco area of Mexico, the patent actually gave him authority over all lands from there to Florida, including the coasts of present-day Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Amichel was, therefore, the first known toponymn ever applied to any part of Texas, and Francisco de Garay was, in a sense, the first governor of Texas.

In June 1523, Garay sailed from Jamaica, ready to re-establish the colony at Pánuco. He landed by mistake about 100 miles north, at the present-day Soto La Marina River, which he called the "River of Palms." He marched southward from there to Pánuco only to find that Hernán Cortés had annexed it as part of New Spain. Garay went to Mexico City to negotiate with Cortés, but he became ill and died there in December 1523.

A map published in Nuremberg, Germany in 1524 provides a crude, very out-of-scale depiction of the Gulf of Mexico, not nearly as accurate as the sketch from Pineda's 1519 voyage. Many of its details cannot be identified with confidence, but it does depict both the Pánuco River and the River of Palms. A label near this area, calling it Amichel Province, is the only appearance of the name Amichel on any map from the period. The map also depicts four unidentifiable river mouths or bays between the River of Palms and the Espíritu Santo, or Mississippi River.

Despite numerous voyages made to the Gulf coast by Spain since Christopher Columbus' discovery of the New World, including voyages not mentioned above, Cortés's New Spain was the only successful Spanish colony on the North American mainland as of the 1520s. Even Florida was still a wilderness, as Ponce de Leon died in 1521, never having settled any part of it. But King Charles was not one to ever stop trying to enlarge the territory, power, and wealth of Spain, and there was always an aspiring conquistador ready to attempt to duplicate Cortés's success. To that end, in 1527, Charles appointed Pánfilo de Narváez, Diego Velázquez's old ally and Cortés's foe, as the new governor of Florida, with the authority to explore, conquer, and settle the entire Gulf coast from the cape of Florida to the river named "River of Palms" by Francisco de Garay.2

It was with great hopes that Narváez set sail from Spain in June 1527 with five ships and 600 men and women in his fleet. His expedition was a disaster and a failure, but it did result in the first European presence on Texas soil. For a thorough account of Narváez's expedition, please see the next article in this topic, "The Narváez Expedition."

By David Carson

Page last updated: October 12, 2022

1The lower Atlantic coast of the present-day U.S. was granted in 1523 to Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, who established a short-lived settlement there in 1526. The crown obviously meant to exclude Ayllón's grant from Garay's. Spain's official master world map, produced by Diogo Ribeiro in 1529, had the lower Atlantic coast labeled as "Land of Allyon" and the Gulf coast as "Land of Garay."

2Narváez's grant included the same territory as Garay's, minus the hotly-contested province of Pánuco, which the crown took from Cortés in 1525 and gave to newcomer Nuño de Guzmán.