Coronado Expedition Timeline

Coronado Expedition Timeline

- Introduction

- Anchoring the Timeline

- Segment 1: From Tiguex to the Ravines

- Segment 2: From the Ravines to Quivira

- Segment 3: The Army's Return to Tiguex

- Segment 4: Coronado's Return to Tiguex

- Timeline

Next: Coronado Expedition Personnel

Introduction

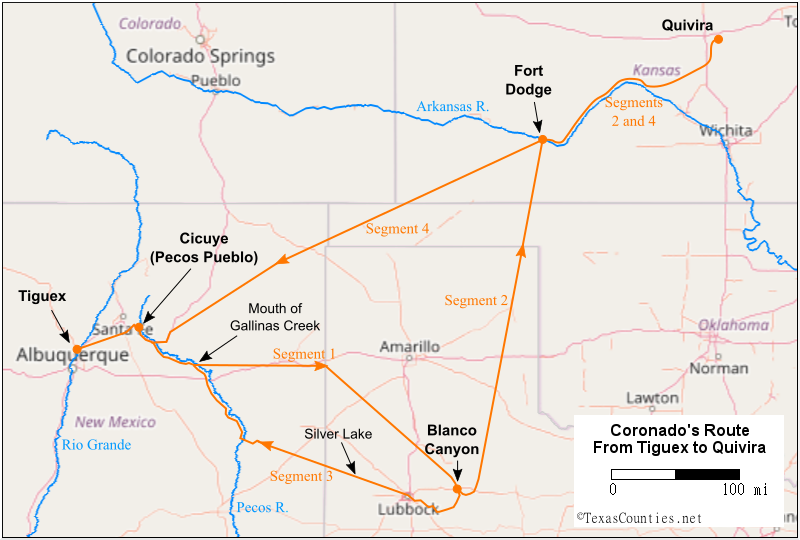

The previous article, Coronado Expedition Route Analysis, presented an interpretation of the route Francisco Vázquez de Coronado took on his expedition through the Panhandle and High Plains regions of Texas in 1541. Our interpretation, which is represented on the map shown below in Figure 1, is based on the small amount of archeological evidence available plus four primary historical sources: 1) a letter written by Coronado to King Charles, 2) an anonymous account called La Relación del Suceso ("The Account of the Event"), 3) a chronicle of the expedition written by a soldier, Pedro de Castañeda, and 4) an expedition chronicle written by another soldier, Juan Jaramillo.

This article extends our analysis with the addition of a timeline. The primary sources give us a few calendar dates, travel time estimates, and seasonal indicators that allow us to estimate when Coronado and the men of his expedition entered and exited Texas and when they visited certain locations. Just as with the previous part of the analysis, the information given in the four primary sources is sometimes confusing and even contradictory, so the timeline and dates we construct from it should be taken as estimates.

Readers who have not read the previous article are urged to do so before reading this one. Readers who are not familiar with the Coronado Expedition may wish to read our article, "The Coronado Expedition in Texas," first.

Anchoring the Timeline

Each of our four sources provides some information, such as the number of days it took the expedition to travel from one place to another along the route, to use in our timeline. Unfortunately, none of the sources provide a concise, stand-alone summary of the expedition. Even worse, wherever two or more sources provide information about the same part of the journey, they never agree exactly. It is impossible, therefore, to construct a timeline without consulting all four sources while at the same time making judgment calls about which one to prefer on a certain point. The need to make such judgment calls should not be taken as an opportunity to shape the timeline arbitrarily, however. Instead, we should use logic and make reasonable assumptions in comparing the validity of one source against another.

Our first assumption is that none of the authors were consciously giving incorrect information about the timeline of the expedition. While it is true that historians often have agendas or biases that can color their accounts and make them tell the story one way when it actually happened differently, there do not appear to be any reasons why any of our sources would have manipulated this timeline. It does not matter, for example, whether a certain portion of the journey took 42 days or 48 days. All contradictions and inconsistencies between the sources, then, are taken to be the result of errors or honest discrepancies in the way their information was obtained, or by errors in transmission.

Our assumption that the authors of all four of our sources intended for their accounts to be true and accurate leads us to a second assumption, which is that two of the sources - namely Coronado's letter of October 20, 1541 and the Relación del Suceso - are to be given more weight on most matters than the accounts of Castañeda and Jaramillo. While Coronado was on the march, he knew he would be making a report later, so he had an incentive to keep track of his progress and to be aware of the calendar. He wrote his letter to King Charles from Tiguex soon after his return from Quivira, when everything he wrote about was no more than six months in the past. At the time he wrote the letter, he had access to aides and others who went on the journey, who could help with the details, if there were some he had forgotten. On a similar note, while the author of the Relación del Suceso is unknown, his frequent inclusion of travel distances, directions, and latitude readings suggests that he was working in an official capacity to document the expedition. Historians Richard and Shirley Cushing Flint speculate that the author may have even been Coronado's secretary. The date that the Relación was written is also unknown, but Flint and Flint believe that it was written either during the expedition or shortly afterward. They also found that wherever the Relación gives distance estimates between two points that are known to us, those estimates are accurate to within 10 to 15 percent.1 This track record for accuracy gives us the confidence to estimates from the Relación on matters that are unclear or require some interpretation. On the other hand, Castañeda and Jaramillo's accounts, while longer and more descriptive than Coronado's letter and the Relación, were both written in the 1560s, twenty years or more after the march ended. Both of the writers were common soldiers on the expedition who had no journal-keeping responsibilities, and do not appear to be drawing from anything but their own memories. It is simply unrealistic to expect that such a person would remember mundane information like dates, number of days traveled, and distances traveled for that long with much accuracy. To his credit, Jaramillo realizes and admits this, with his tendency to use inexact wording such as "I believe we had been traveling twenty days or more," (rather than "we marched twenty days,") and his liberal use of phrases like "if I remember rightly." Castañeda does not usually qualify himself in this fashion, but we should not take his less ambiguous wording to mean he is more reliable. Self-confidence is not a substitute for accuracy.

Despite the above assumptions, the first anchor point for our timeline is a date given by Jaramillo. It pertains to the date that Coronado and his small company of horsemen came to and crossed a river near the province of Quivira while on what we call Segment 2 of the journey. Jaramillo writes that the expedition came to this river "on Saint Peter and Paul's day."2 This is a reference to the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, a day on the liturgical calendar of the Roman Catholic Church and some other Christian denominations, which is observed every year on June 29. We consider remembering a date in this fashion to be much more reliable than remembering it by month and day, for the same reason that it is easier to remember that something happened on St. Patrick's Day or your sister's birthday than remembering the date. This is especially true when considering the longstanding practice of Spanish explorers of naming rivers after the day on the liturgical calendar that they were discovered.3 Jaramillo later reiterates that on the return trip from Quivira to Tiguex, they crossed "a river called Saint Peter and Paul's"4 at the same place where they had crossed it previously. As explained in the previous article, this river is taken to be the Arkansas, and the crossing is taken to be at Fort Dodge, Kansas. Jaramillo was in the company of Coronado's expedition that went to Quivira, so this would be something he had first-hand knowledge of. The other expedition chronicles do not supply any information that contradicts or is inconsistent with Jaramillo on this point. And, for what it is worth, Jaramillo does not qualify this piece of data with hedge words, which he so often does in other instances, perhaps indicating a higher degree of certainty on his part. For these reasons, we choose to fix Coronado's first crossing of the Arkansas River at Fort Dodge on June 29, 1541 and build the rest of the expedition timeline around this date.

Our next timeline anchor point is the date that the expedition left Tiguex to begin its march to Quivira. For this, we have two options: Coronado wrote, after his return to Tiguex, "I started from this province on the 23d of last April."5 Castañeda, on the other hand, writes, "The army left Tiguex on the 5th of May."6 This apparent discrepancy of 12 days is quite large, but there is a good explanation for it. Castañeda's original manuscript, which was written in the 1560s, is lost. The Castañeda manuscript that is the basis for all modern transcriptions and translations is a copy made by the scribe Bartolomé Niño Velázquez in 1596 and now kept in the New York Public Library. In 1582, during the interval between the time of Castañeda's original composition and Velázquez's copy, Spain changed from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. Flint and Flint theorize that Velázquez converted Castañeda's dates to the new calendar, which was done by adding 10 days to them. If this is the case, then Castañeda actually wrote that Coronado left from Tiguex on April 25. This reduces the discrepancy between Castañeda and Coronado on this matter from 12 days to 2.

If no other information were available, then going by our earlier assumption that Coronado is a more reliable source for timeline-related information than Castañeda, we would simply declare that April 23 is the correct date. There is, however, some other information that can help us make this decision. The number of days from April 23 to June 29, inclusive, is 68. The number of days from April 25 to June 29, inclusive, is 66. As the next section of this article will show, the chronicles account for at least 65 travel days between these two locations, and this does not include two stops - one lasting four days and another lasting "many days." It is difficult enough to squeeze the events described by the chronicles into 68 days, let alone 66. Coronado's departure date from Tiguex of April 23, therefore, fits the other information given in the chronicles better. For this reason, and because of our general tendency to give Coronado's dates more weight than Castañeda's, we accept it as the second anchor point of our timeline.

Segment 1: From Tiguex to the Ravines

The first segment of Coronado's route through Texas began on the Rio Grande at the village of Tiguex, where Coronado's army spent the winter of 1540-1541. Castañeda writes that the river was frozen for four months, and men had been crossing it on horseback. When the river thawed, Coronado gave the order to move out. Coronado wrote that he started from Tiguex on April 23. As explained in the previous section, Castañeda gave a different date, but we take Coronado's date to be correct.

Jaramillo writes that in four days, the expedition came to Cicuye. Along the way, it passed two villages whose names Jaramillo did not know.7 Castañeda does not say how long it took to get from Tiguex to Cicuye on this occasion, but he does state that a previous journey from Tiguex to Cicuye, led by Captain Alvarado, took five days.8 He also wrote that Cicuye was 25 leagues from Tiguex. Since a league was intended to represent the distance a man can walk in a day, making this trip in four days is entirely reasonable. We take, therefore, Jaramillo's statement that it took four days to reach Cicuye as accurate, and conclude that the army arrived there on April 26.

None of the sources mention the expedition stopping at Cicuye. It does not hurt to assume that the army spent the night there, but it probably did not stay any longer than that, for the men had been waiting for months to get underway, probably felt that they were well-provisioned, and were eager to find their cities of gold. The expedition presumably left Cicuye on the morning of April 27.

Jaramillo writes that the expedition "came to" the Cicuye (Pecos) River in three days.9 Since the village of Cicuye was only about a mile from the river, this means that, instead of crossing the river near the village, the expedition traveled parallel to and west of it for some distance, just as Interstate Highway 25 does to this day. Jaramillo mentions crossing the river, but does not explicitly state that it was crossed on the same day the expedition "came to" it, so it could be the case that the army first came in view of the river in three days and then marched along its west bank for some distance before crossing it. Castañeda writes that the expedition "came to" the river after four days and had to stop to build a bridge across it. He writes that this effort took four days.

In the previous article, we identified the expedition's crossing of the Pecos River as somewhere below its junction with the Gallinas River. That location is about 60 miles downstream from the ruins of Cicuye. Because the army would have been marching downhill all the way, making this distance in three days is possible, but covering it in four days is more realistic. We would be inclined to give more weight to Castañeda here, especially because of his added detail of stopping for four days to build the bridge - something none of the other writers mention - except that Coronado writes, "after nine days' march I reached some plains..."10 If the army crossed the Pecos River below the Gallinas River, it would have taken a minimum of two more days to reach the plains of the Llano Estacado. This means it took seven days of marching to get to the Pecos River: four days from Tiguex to Cicuye, and three days from Cicuye to the river. After another two days' march, Coronado was on the plains.

Castañeda's statement that it took four days to build a bridge across the river requires some examination. As we have already pointed out, the travel times given in the chronicles for the various segments of the journey between Tiguex and the Arkansas River can barely fit within the allotted span of 68 days between April 23 and June 29. The sum of any stops or delays along the way could not have been more than four days, so if the army stopped at the Pecos River for four days to build a bridge, it would have had to move nonstop from there to the Arkansas River, which goes against other statements in the texts. Fortunately, there is a way to include this four-day delay without compromising our timeline. Students of the Coronado Expedition will remember that this mass of horsemen, foot soldiers, priests, servants, livestock, and equipment rarely moved as a single body. From the beginning, Coronado frequently dispatched captains to move out in front of the main body, and he also sometimes had groups stay behind. For example, he had Melchior Díaz explore the Sonora River valley while he was marching with the main body of the army from Compostela to Culiacan. He later had Díaz remain behind at the village of Hearts while he marched toward Tiguex. He also sent several scouting and reconnaissance parties out to investigate the Grand Canyon, the Colorado River, and a long stretch of the Rio Grande both north and south of Tiguex. Castañeda tells us that for much of the march from Cicuye to the ravines, Coronado went with an "advance guard," which was guided by The Turk, and that this group made piles of stones and cow dung for the rest of the army to follow.11 Throughout his narrative, Castañeda always writes from his perspective in the main body of the army, at the rear. Jaramillo seems to have been a member of the advance guard, as does the writer of the Relación. It is logical to suppose, then, that Coronado and his advance guard forded or swam across the Pecos River so that at least part of the expedition could keep moving, but in order to get everyone across - including the cattle, sheep, and wagons - a bridge had to be constructed. What this means for our timeline is that while Castañeda's part of the expedition was delayed at the Pecos River for four days, Coronado was not - he reached the Llano Estacado on May 1, nine days after leaving Tiguex. For Castañeda to be the only one of the four chroniclers who was affected by the delay to build the bridge could explain why he was the only one to mention it.

The next bits of information we have about the expedition's timeline have to do with when Segment 1 ended, which was at a place where Blanco Canyon opens up to "a league wide from one side to the other."12 This location, which we interpret as being in Crosby County, is the furthest point from Tiguex that the army marched. Coronado tell us indirectly that Segment 1 required 35 days of travel.13 If he did not stop between Tiguex and Blanco Canyon - and he does not mention stopping - that means this segment ended on May 27. Castañeda, differing slightly, writes, "up to this point they had made thirty-seven days' marches."14 A 37-day march would have Segment 1 ending on May 29, or on May 31 if we also use Castañeda's later starting date. As usual, though, for the reasons already stated, we opt to use Coronado's figures.

Castañeda writes that the distance from Tiguex to this location was 250 leagues. Using his own figure of 37 travel days, he correctly calculated the expedition's traveling speed as "6 or 7 leagues a day."15 This amounts to about 15 to 18 miles per day. The Relación del Suceso, however, gives the total distance of this segment as only 150 leagues.16 This happens to be an excellent approximation of the actual distance, along our interpreted route, of about 380 miles. Using Coronado's figure of 35 days for the journey, the army covered only 4 leagues, or 11 miles, per day. This is not a very impressive traveling speed, and is certainly not the "6 or 7 leagues a day" that Castañeda remembered.

With the information obtained so far - some from the texts, and others from calculation - it seems that Coronado and his army covered the first 120 miles of the expedition, when they were in the vicinity of the native settlements, in seven days, at the respectable pace of 17 miles per day, but that they slowed down to 9¼ miles per day, or 260 miles in 28 days, to cross the open and unsettled plains. Even though the topography of the Llano Estacado is flat, there are several things that could have slowed them down. Most of all, food and water were scarce. While there were bison to hunt, there still could have been issues with finding water and wood for cooking. There did not seem to be anything for the horses to eat except low-growing "buffalo grass." Jaramillo writes, "we came to be in extreme need from the lack of food."17 Such hardships can easily slow the progress of a large army.

By our calculations, Coronado crossed the New Mexico-Texas state line, possibly at Deaf Smith County, on May 11, which was the 19th day of travel and the 12th after crossing the Pecos River. Depending on which source one wants to use, Coronado and his men had met the Querechos 3 to 7 days earlier and had been among the bison for the last 5 to 7 days.

None of our four sources describe the journey from the Querechos' territory to the main camp sufficiently well for the purposes of making a timeline. Based purely on the expedition's apparent traveling speed of 9¼ miles per day, they were at the Jimmy Owens site in Floyd County on May 25. This may have been the afternoon of the hailstorm that, according to Castañeda, scattered the horses and broke the pottery.18 The expedition had just recently - perhaps even earlier that same day - met the group of Indians who remembered meeting Cabeza de Vaca and his comrades six years earlier.

As noted earlier, the expedition came to a stop in Crosby County, probably on May 27. This segment included 35 days of travel over about 380 miles, at an average travel speed of about 11 miles per day.

Segment 2: From the Ravines to Quivira

When the expedition came to a place where the ravine that we interpret to be Blanco Canyon was a league wide, it met a new group of natives - the Teyas. These natives informed the Spaniards that Quivira was to their north, whereas their guide, The Turk, had been leading them east or southeast, toward Florida. Another Indian in Coronado's company, Ysopete, had been telling Coronado this all along. General Coronado then called a meeting of his captains to make a decision on what to do next. They decided that the general would proceed to Quivira with a small company of horsemen, while the rest of the army would wait. After a few days, Coronado would send a messenger back with instructions for the army to either follow after him or return to Tiguex. Coronado placed the Turk in chains and entrusted Ysopete to guide him to Quivira.

According to Coronado, the author of the Relación del Suceso, and Jaramillo, the company Coronado took to Quivira consisted of thirty horsemen. The total number of persons who went was undoubtedly higher, though, for these horsemen did not include The Turk, Ysopete, possibly other native guides or servants, a friar named Juan Padilla, and other miscellaneous personnel who the chroniclers tend to ignore in their enumerations. Furthermore, Castañeda writes that the company included "a half dozen foot-soldiers."19 The reason this matters for the timeline is that a group in which everyone was on horseback might be expected to move faster than a group where there were some walkers. One might wonder, then, why Coronado decided to compose his small company of mostly horsemen if they were not going to be able to travel any faster than a group of men who were entirely on foot. The answer is probably that the horses were not meant specifically to get them to Quivira more quickly, but that they would be needed to carry back the gold and other treasures the men hoped to find there. Castañeda writes, "The Turk had said when they left Tiguex that they ought not to load the horses with too much provisions, which would tire them so that they could not afterward carry the gold and silver."20 Even though Ysopete had told Coronado that The Turk was lying about the gold, and Coronado was now listening more to Ysopete, he still could not pass up the chance that Quivira would make him as rich and famous as Cortés and Pizzaro.

The Relación del Suceso gives the travel time between Blanco Canyon and Fort Dodge as 30 days,21 while Jaramillo remembered that it took "more than thirty days' march" to get there.22 We are going to use the Relación's figures over Jaramillo's for the same reasons that we used Coronado's over Castañeda's earlier - first, because the Relación del Suceso was written either during or soon after the expedition, while Jaramillo wrote his account decades later, and also because the Relación's information fits the timeline better. The interval between the end of Segment 1 (May 27) and the date Coronado's party reached the Arkansas River (June 30) is 35 days, inclusive. Coronado did not make his decision to change guides, recompose his forces, and continue on his way immediately, however. His decision to demote the Turk and promote Ysopete came after Coronado sent out scouts who found the Teyas, interviewed them about Quivira, and learned from them that the Turk had been deceiving him. Castañeda also writes that the expedition "rested several days"23 in the ravine, where the men found nuts, berries, and fowl to eat, and did some more exploring before Coronado made the decision to proceed to Quivira. Also note that where Winship's translation reads "several days," Castañeda's original Spanish reads muchos días,24 which is better translated as "many days." Our interpretation, therefore, is that the expedition camped for four nights, and that on the morning of May 31, Coronado and his party of horsemen started on Segment 2. Thirty days later, June 29, they were at Fort Dodge on the Arkansas River.

The distance between Blanco Canyon and Fort Dodge is about 300 miles, meaning the men covered about 10 miles per day. As Jaramillo accurately recalled, these were "not long marches."25. Based on this traveling speed, Coronado crossed the present-day Texas-Oklahoma state line, probably in Lipscomb County, on June 23.

The trip to Quivira took 48 days, according to Castañeda,26 or 42, according to Coronado.27 As usual, we prefer Coronado's number because it was written down earlier. Additionally, Castañeda was not part of the group that went to Quivira, so he would have had to have learned this information from someone else, thus increasing the chances of there being a mistake. Jaramillo did go to Quivira, but, like Castañeda, he was drawing from distant memories. His accounting of "more than thirty days' march," "after marching three days," and "about three or four days still farther" adds up to a minimum of 37 days, with the suggestion that it could have been more. Coronado's figure of 42 days still holds up. This means he arrived at the settlements of Quivira on July 11, 1541. In the last 12 days, he and his men traveled about 14.6 miles per day, which is an improvement over their somewhat relaxed 10 miles-per-day pace of earlier.

Segment 3: The Army's Return to Tiguex

Castañeda is the only author out of the four sources used in our analysis who was still with the main army after Coronado took his small company to Quivira, and he is also the only one who gives any information about the army's return to Tiguex. He writes that when Coronado left, he gave the army orders to wait in the ravine. Within eight days, he would send messengers back with instructions for the army to either proceed to Quivira or go back to Tiguex.

Castañeda further writes that the guides Coronado took with him "ran away during the first few days,"28 so Coronado sent a captain back to get new guides from the Teyas. This captain, Diego Lopez, also brought Coronado's orders that the army was to return to Tiguex. Instead of leaving immediately, however, the army stayed put for "a fortnight," hunting bison and preparing jerky for the men to take with them. Once the army left the ravine, it took only 25 days to reach Tiguex, as opposed to the 37 days (or 35 days, if Coronado is right) the eastbound journey had taken. Castañeda credits the Teyas for taking the army "on a more direct road" than the route they had taken earlier. Led by Captain Don Tristan de Arellano, the army reached Tiguex "about the middle of July."29

According to our analysis, Coronado left the army on May 31. His plan was to send messengers back to the army with new orders within eight days, and he in fact sent messengers back within "a few days." Castañeda writes that the army "spent a fortnight" in the ravines. The most plain way to read the text is that this fortnight began after Coronado's messengers returned, but it could also possibly mean that it began when Coronado left, or even when the army first arrived on May 27. The date the army began its departure from Blanco Canyon, therefore, could have been as early as June 10 or as late as June 22. To correspond with Castañeda's statement that the 25-day return trip to Tiguex ended in mid-July, however, a date at the later end of this range must be used. This indicates that the two-week interval in which the men hunted bison and made jerky began after Coronado's messengers returned. Castañeda states that the messengers were due to come back "within eight days," but does not state how long it actually took them to come back. If they did indeed return eight days after Coronado left, then the fortnight began on June 8, the army began its return on June 22, and it arrived in Tiguex on July 16 - the middle of July. These are, of course, only estimates.

To cover 400 miles in 25 days, the army would have moved at 16 miles per day. While this is quite a bit faster than the speed with which it traveled east, it is still reasonable, especially considering Castañeda's statements about how the men prepared jerky before leaving and how well the Teyas guided them across the plains. At this speed, the army would have crossed the Texas-New Mexico state line, possibly in Bailey County, on its ninth day, or about June 30.

Segment 4: Coronado's Return to Tiguex

As stated earlier, Coronado and his company arrived at the settlements of Quivira on July 11, according to our timeline. He did not find any gold or other wealth, even after sending "captains and men in many directions."30 Coronado wrote that he spent 25 days in the province of Quivira,31 then began his return to Tiguex. This means that Coronado took his men out of Quivira on August 5, 1541. Castañeda agrees, stating "it was early in August when he left."32

None of the three writers who went to Quivira left a record of how long the return trip took, or on what date it arrived back at Tiguex. We must rely, then, on Castañeda, who writes, "it took him forty days to return."33 When Castañeda wrote this, however, he was explaining how part of the army, led by Captain Arellano, had gone out in search of the general, anxious over the fact that he had not yet returned. It so happened that when Arellano was at Cicuye, Coronado arrived there, then he "at once set off for Tiguex." In context, Castañeda's statement that it had taken 40 days to return seems to refer to his return to Cicuye. The date would have been September 13. Coronado's average traveling speed, if our estimate of 610 miles is correct, minus the 64 miles from Cicuye to Tiguex, was 13½ miles per day. He would have arrived at Tiguex four days later, on September 17.

As stated in the previous article, it is unlikely that Coronado passed through Texas at all on the way from Quivira to Tiguex. If he did, though, he probably only passed through a little bit of Dallam County, in the state's northwest corner. Using a departure date of August 5 and a traveling speed of 13½ miles per day, the date of this very brief visit to Texas would have been September 1, 1541.

Coronado Expedition Timeline

Our completed timeline of the Coronado Expedition is presented in the table below. The two dates in bold are the anchors around which the rest of the timeline is constructed. All other dates are based either on intervals of time stated in the texts or are calculated from estimated travel distances and speeds.

Note that, as with the rest of our analyses of the Coronado Expedition, this timeline only deals with the segments of the expedition that took place in the vicinity of Texas.

| Date | Segment | Event | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 23, 1541 | 1 | Coronado and the army depart from Tiguex. | Coronado |

| April 26 | 1 | Coronado and the army arrive at Cicuye. | Jaramillo |

| April 29 | 1 | Coronado and the army arrive at the Pecos River. Coronado and the advance guard cross it, while the rest of the army stops for four days to build a bridge. | Jaramillo and Castañeda |

| May 1 | 1 | Coronado and his advance guard reach the Llano Estacado. | Coronado |

| May 11? | 1 | Coronado and his advance guard cross from present-day New Mexico into Texas. | calculated |

| May 25? | 1 | Coronado, his advance guard, and/or his army are hailed on in Floyd County. | calculated |

| May 27 | 1 | The army comes to a halt in Crosby County. | Coronado and Castañeda |

| May 31 | 2 | Coronado begins taking a company of soldiers to Quivira. | Relación del Suceso |

| June 8? | 3 | The army receives orders to return to Tiguex. | Castañeda |

| June 22? | 3 | Captain Arellano leads the army out of Crosby County. | Castañeda |

| June 23? | 2 | Coronado crosses from Texas into Oklahoma. | calculated |

| June 29 | 2 | Coronado crosses the Arkansas River at Fort Dodge. | Relación del Suceso |

| June 30? | 3 | Arellano and the army cross from Texas into New Mexico. | calculated |

| July 11 | 2 | Coronado arrives at Salina, Kansas. | Coronado and Relación del Suceso |

| July 16? | 3 | Arellano and the army arrive at Tiguex. | Castañeda |

| August 5 | 4 | Coronado begins the march from Quivira back to Tiguex. | Coronado |

| September 1? | 4 | Coronado makes his closest approach to Texas of his return trip, possibly passing through Dallam County. | calculated |

| September 13 | 4 | Coronado meets Arellano and part of the army in Cicuye. | Castañeda |

| September 17? | 4 | Coronado arrives at Tiguex. | calculated |

By David Carson

Page last updated: November 2, 2018

1Flint and Flint, p. 494.

2Jaramillo, p. 587.

3Not every day of the calendar had a corresponding liturgical celebration or obligation, but the majority did. June 28 and June 30 also had liturgical significance, so even if the river was actually found either a few days before or after a liturgical day and Jaramillo was "forcing" its discovery onto one, I assume that the only way the day would have been determined to be Saint Peter and Paul's Day is if it were actually June 29, not a day proximate to it.

4Jaramillo, p. 591.

5Coronado, p. 580.

6Castañeda, p. 503

7Jaramillo, p. 587.

8Castañeda, p. 491.

9Jaramillo, p. 587.

10Coronado, p. 580.

11Castañeda, pp. 504-505.

12Castañeda, p. 507.

13"I traveled forty-two days after I left the force ... after having journeyed across these deserts seventy-seven days, I arrived at the province they call Quivira..." Coronado, pp. 581-582.

14Castañeda, p. 507.

15Castañeda, pp. 507-508.

16Relación del Suceso, p. 577.

17Jaramillo, p. 588.

18Castañeda, p. 506.

19Castañeda, p. 581

20Castañeda, p. 512.

21"... after thirty days' march we found the river Quivira..." Relación del Suceso, p. 577.

22Jaramillo, p. 589.

23Castañeda, p. 507.

24Castañeda, p. 442.

25Jaramillo, p. 589.

26Castañeda, p. 509.

27Coronado, p. 581.

28Castañeda, p. 508.

29Castañeda, p. 510.

30Coronado, p. 582.

31Coronado, p. 583.

32Castañeda, p. 512.

33Castañeda, p. 512.

- Anonymous - "Relacion del Suceso" - translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C. 1896

- Castañeda, Pedro de - "The Narrative of Castaneda," translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C., 1896

- Coronado, Francisco Vazquez - Letter to King Charles written October 20, 1541, translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C., 1896

- Jaramillo, Juan - "The Narrative of Jaramillo," translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C., 1896

- Flint, Richard and Flint, Shirley Cushing - Documents of the Coronado Expedition, 1539-1542, Southern Methodist University Press, 2005.