The First Christmas in the United States

The First Christmas in the United States

The first Christmas observed in the present-day United States occurred in Texas on December 25, 1528. Five boats carrying men from Pánfilo de Narváez's failed expedition to Florida came to rest at various places on the Texas coast in November. When they arrived, the expeditionaries were hungry, cold, and separated from each other by hundreds of miles of sparsely-populated wilderness. By Christmas, many had already died. The rest had long since given up their dreams of finding gold and were now wishing only to survive and escape.

Christmas in the New World

Christmas is the day celebrated worldwide to commemorate the birth of Jesus Christ. It is one of the most important days of the year for Christians, who observe it with church attendance, Bible reading, songs, gift-giving, meals with family, and a day off from work. Non-Christians who live in countries where Christianity is or has been the dominant religion usually join in this celebration, albeit with some of the religious aspects modified or removed.

During the Age of Discovery, which began in the late 1400s, the country of Spain sent men in ships to discover, explore, conquer, and settle new lands. At that time, Roman Catholicism was the official religion of Spain. Church and state were intertwined, as many of Spain's government officials and bureaucrats were also priests, bishops, archbishops, and cardinals in the Roman Catholic Church. Spanish law required that every person leaving Spain on a ship bound for its overseas colonies, from the noblest conquistador to the lowest slave, be a member of the Church. Every conquistador and governor's charter commanded him to observe the Church's doctrines and customs. Priests and friars were usually sent with the first colony ship, because Spanish society had numerous institutions, such as confession, marriage, baptism, and last rites, that had to be performed by a qualified member of the clergy. These clergymen also led the observance of the numerous festival days on the Church calendar, including Christmas, which was observed on December 25.1 Because of the elevated place of Christmas on the Church calendar, it is safe to say that wherever a group of Spaniards was on December 25, whether or not a priest was there to lead them, they were celebrating or observing Christmas in some way.

The first Christmas to be celebrated in the Western Hemisphere took place on December 25, 1492 in present-day Haiti. Christopher Columbus, on his maiden voyage across the Atlantic, stopped on the north coast of the island of Hispaniola on December 24 and founded a small colony. He named it La Navidad - "Christmas." While that colony lasted less than a year, Columbus and other explorers returned to found new colonies in the Caribbean islands. The first Spanish colony on the island of Puerto Rico - now a territory of the United States - was placed there in 1508, so the first Christmas celebrated in Puerto Rico would have been in that year.

The same man who founded the colony on Puerto Rico, Juan Ponce de León, would subsequently make a voyage that earned him credit as the official discoverer of Florida. That voyage, taken in the spring of 1513, did not last through Christmas. Over the next several years, there were other voyages to Florida and other parts of the present-day United States by men including Alonso Álvarez de Pineda, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, and a return voyage by Ponce de León, but none of the known expeditions took place during Christmastime, as the winter was widely viewed as the least favorable time of year for going on a sea voyage.

Order your copy of Children of the Sun: Following in the Footsteps of Narváez and Cabeza de Vaca, by David Carson of TexasCounties.net, available in E-book and paperback formats.

The first time that Spaniards - or people from any other Christian country - were documented to be in the United States proper at Christmastime was in 1528. They came under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez. Narváez and his five ships anchored off the coast of Pinellas County, Florida on April 9, 1528. He then took his men, minus his ships, on a foolhardy search for gold that saw them wind up at St. Marks Bay, south of present-day Tallahassee. With their numbers dwindling due to illness, hunger, and continued attacks from the natives, the men decided to build boats and sail west, following the Gulf Coast, until they reached the Spanish colony at Panuco, near present-day Tampico, Mexico. About 250 men crowded into five small boats and launched them on September 22.

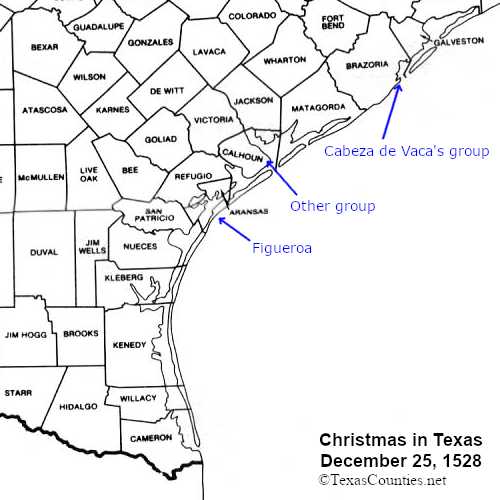

In their five boats, the men slowly made their way west along the coasts of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana for over a month. When they tried to cross the mouth of the Mississippi River, the boats were driven out to sea by the river's strong current. They subsequently became separated from each other. Each boat eventually made it to Texas. The men on one boat were thoroughly massacred by natives upon their arrival. The men of the other four boats ended up combining into two large groups - one in Brazoria County, and the other in Calhoun County. Through a variety of mishaps, all of their boats became lost or too damaged to use, making the men castaways.

December 25, 1528

One group of about eighty Narváez Expedition survivors landed on a small peninsula of Brazoria County at the west end of Galveston Bay now sometimes called Follet's Island. These men met two clans of natives - one called the Capoques, and the other, Han. While their experiences with natives up to that point had been mostly bad, the Capoques and Han were friendly to them. The Spaniard's leader, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, asked if they could stay with them, and the natives happily obliged them.

The Capoques and Han initially viewed their European visitors with a sense of apprehension, even wonder. They did not know who these men were or why they were there, but they knew they came in from the sea on boats. The natives had canoes, but they only used them to fish from and to travel around Galveston Bay, not to traverse the ocean. So much about the Spaniards was different: not just their watercraft, but their beards, their trinkets made of glass and metal, their clothing, their ritual of moving their hands over their faces in a cross shape when they prayed. The natives got the idea that these men were special, and they even involved them in their healing rituals, inviting them to serve as their shamans. But the longer the Spaniards stayed with them, the more disillusioned the natives became. The Spaniards did not know how to fish with a bow. They were bad at pulling edible roots from the shallow ponds. Unable to fish, unable to forage - no wonder they were always hungry! Furthermore, the cloud of death hung over them. Day by day, one Spaniard after another died, either from illness or malnourishment. The natives began to die of illness also. Neither the natives nor the Spaniards at that time understood the nature of bacterial infection, but the natives nevertheless began to view the Spaniards as deathbringers. At one point during the winter, they surrounded the small number of Spaniards who were still alive and drew their bows to end their lives. But one native then spoke up and pointed out that if the Spaniards had the power to kill, they wouldn't be dying in even greater numbers than them. He recommended leaving the rest of the Spaniards, who had done them no harm, alone, and they did.

The accounts written by the survivors focus heavily on geography and the struggle for survival. They pay no attention to how the castaways passed their few non-working moments. They do not explicitly say that they observed Christmas, or how. Nevertheless, we can be positive that they did, because of who these men were. These were men who named rivers and bays according to the day on the Catholic festival calendar they discovered them. They referred to themselves collectively not as Spaniards or Europeans, but Christians. They carried rosaries, prayer books, crucifixes, and images of Mary around with them. They thanked and praised God when something good happened to them, and begged for forgiveness of their sins when something bad happened. They were constantly conscious of their faith and religious traditions, even though they were lost and hundreds of miles from a church.

Between November and April, the number of Europeans on Follet's Island diminished to 16. How many were alive on December 25 is hard to guess, but most of the deaths probably came early on. Those who remained became scattered. The native clans never stayed in the same place for very long, so when they moved, some of the European survivors went with one clan, while some went with another, and others stayed on Follet's Island. At least one of the survivors was a clergyman. His home province in Spain was Asturias. The survivors who wrote about him years later only remembered his nickname, Asturiano. This religious man certainly would have kept track of the days and known when December 25 came. He would have done his best, under the circumstances, to make sure that he and any survivors who were with him remembered Jesus's birth and, at a minimum, recited some prayers and Bible verses. All of the other survivors in their small groups on and around Follet's Island would have probably tried to do something, however small, to observe Christmas. The job of staying alive in the wilderness was one of constant toil, however - every daylight hour was spent looking for food, gathering wood for fires, carrying water, or some other form of heavy labor. In that respect, Christmas would have been no different than any other day.

The natives of Follet's Island were, most likely, ancestors of clans that were known in later centuries as Karankawa. Karankawa culture was more primitive than most native American cultures at that time. Their beliefs about deities and the afterlife were unsophisticated. Spanish missionaries found the Karankawa particularly difficult to teach Christianity to because they had such a scanty set of beliefs to build upon, and furthermore, they did not seem to have any curiosity about what anyone else believed. The survivors of the Narváez Expedition do not write about making any effort to teach Christianity to the natives of Follet's Island. Perhaps this is because they made no attempt, or perhaps it is because their attempts did not go anywhere. If the Europeans did try to explain to the Capoques and Han why Christmas Day was sacred to them, they probably did not care.

Four of the castaways who landed on Follet's Island did not stay there for the winter. They felt that they were strong enough to proceed to Panuco on foot, so they began walking down the Texas coast. A few days after they left, however, the north winds increased and the temperatures dropped. Two of them died within a week. The other two, who were named Figueroa and Méndez, made it as far as St. Joseph Island in Aransas County. There, they were taken in by natives who were also probably Karankawa-related. Like their comrades on Follet's Island, Figueroa and Méndez had to work hard every day to earn their keep. Unlike their comrades up the coast, however, they were not free to leave when they wanted to. When Méndez tried to run away, the natives killed him. Figueroa remained with them as their slave. Whether Méndez was still alive on December 25 is unknown, but Figueroa was. He might have been unsure exactly when Christmas Day came, and certainly did not have much of a celebration of it.

While Cabeza de Vaca's group was hunkering down for the winter on Follet's Island and Figueroa was stuck in Aransas County, another group of Narváez Expedition survivors was between them, in Calhoun County. These men came in two boats that landed further up the coast. They made it as far as Matagorda Island, using their one good boat to cross Cavallo Pass, but then that boat was lost, with their sick governor, Pánfilo de Narváez, in it. Disheartened, and with temperatures dropping, they decided to cross over to the mainland and find a place to spend the winter. They found a wooded area, perhaps near present-day Port O'Connor. A native clan called the Quevenes saw them arrive and vacated the area to them. At first, the Europeans thought they would be alright: they had fresh water, firewood, and seafood. But the foraging lifestyle requires constant movement, so that the depleted resources of an area can renew themselves. The men ran out of food and resorted to cutting up the bodies of their dead, drying them over a fire, and eating them like jerky. Morale was abysmal. One man got so fed up with the new leader's treatment of the survivors that he struck him with a club, killing him - the first recorded homicide of one European by another in U.S. history.

As with the other group, we do not know how many of the initial 80 or so men in this party were still alive on December 25. This group included at least two Franciscan friars. Since the men apparently stayed together and were not in the custody of natives, they had the best chance of having anything close to a traditional Christmas observance. It would have been important to these men, under these bleak circumstances, in this utterly unknown, foreign land, to draw upon their faith in their Lord Jesus.

1529 through 1532

By April 1, 1529, fewer than 20 castaways from the initial 160 or so were still alive. Some tried to continue to Panuco, but all who made this attempt either died or were killed or captured by natives on the Texas coast. By December 25, 1529, there were only eight to ten castaways left alive, scattered in up to six Texas counties. One can only speculate as to whether any of them knew when Christmas Day came, or whether they took special notice of it. By December 25, 1532, the number of survivors had been reduced to seven. Two of them - Figueroa and Asturiano - had become permanently separated from the rest. No one knows how long they lived or whether they ever made it out of Texas.

December 25, 1533

In the spring of 1533, Cabeza de Vaca and one other man who had remained in the Galveston Bay area since their boat brought them there walked down to Matagorda Bay and were taken across it by natives. They found out from natives on the other side that three of their comrades were alive in that area, but they were living hard lives of servitude and abuse. Cabeza de Vaca's companion, Lope de Oviedo, decided that he did not want to continue. Instead, he went back across Matagorda Bay with the natives that brought him, and was never seen again.

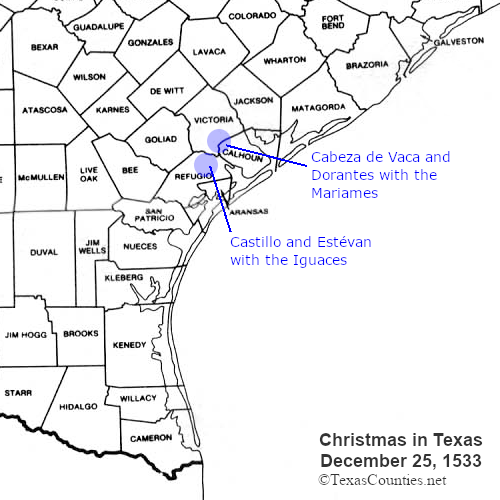

Oviedo's departure left Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes, Alonso del Castillo, and Dorantes's slave, Estévan, as the only survivors of the Narváez Expedition who history has any information about. Cabeza de Vaca became a slave of the Mariames, who were also holding Dorantes. They lived on the east side of the lower Guadalupe River, in northwest Calhoun and/or south Victoria County. The Iguaces, who held Castillo and Estévan, were neighbors of the Mariames. They lived on the west side of the Guadalupe, in Refugio County. The four castaways were occasionally able to see each other, and they tried to coordinate an escape together in the fall of 1533, but their plans fell apart. They spent Christmas of 1533 with their respective captors. By this time, it had been too long since they had seen a calendar, and they had lost track of the days. The patterns of their lives were now governed by natural cycles, such as the phase of the moon and the seasons in which various foods were foraged. It is unlikely that they forgot Christmas completely, but they probably just picked a day that seemed about right and made a token observance, reminding themselves that no matter how long they had been in the wilderness, they were still Christians.

December 25, 1534

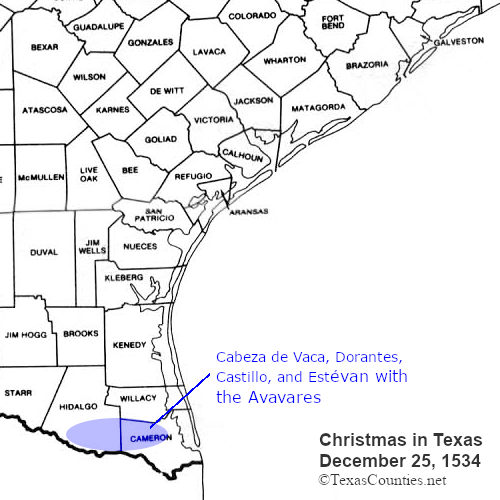

In the summer of 1534, the Mariames and Iguaces made their annual migration to south Texas to forage tunas, or prickly pear cactus fruit. In late September, as the tuna season was ending, Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, Castillo, and Estévan escaped from their captors. All four of them found a clan called the Avavares, who were leaving the south Texas prickly pear fields to go to their winter home in the lower Rio Grande Valley. These people informed them that, to their knowledge, Figueroa and Asturiano were still alive and living on the coast, but there is not enough information to know whether they were still in Texas. This is the last time those two men are mentioned in history.

The Avavares treated the castaways not as slaves or servants, but as honored guests. Like the Capoques and Han on Follet's Island, the Avavares asked them to be their medicine men, or healers. Neighboring clans even came to the Avavare camp to see them and be healed by them, and they gave them food, flints, and other items. The castaways still had to work hard to find food and do the other chores required to survive, but they enjoyed such a high status in Avavare society that they decided, as eager as they were to return to Spanish civilization, to stay with them for the winter. Again, they did not know the exact date when Christmas of 1534 came, but they surely picked one and held some kind of celebration. It was the first Christmas the four of them celebrated together since 1528. They were probably in present-day Hidalgo or Cameron County on December 25, 1534.

The castaways were treated so well by the Avavares that they remained with them well past the end of winter. They did not leave until June of 1535. They crossed the Rio Grande in Hidalgo County, originally planning to walk to Panuco, as had been their goal for the past several years. They began to worry, however, about crossing the coastal territory between them and Panuco. They had formed the opinion that all of the coastal tribes were inclined to cruelty and of a bad disposition. They did not want to come this far only to be taken as slaves again. They opted to go west, over two mountain ranges and a vast desert, adding another ten months to their journey. They spent Christmas of 1535 with some natives in the Sonora River Valley in northwest Mexico. By April 1536, they made contact with other Spaniards on Mexico's west coast, and the Narváez Expedition finally came to an end.

The next Christmas to be observed in the present-day United States would be by members of Hernando De Soto's expedition in 1539.

By David Carson

Page last updated: November 23, 2022

1All 16th-century dates on this page are based on the Julian calendar, which was in use at that time. Today, the U.S. and most of the world uses the Gregorian calendar. To convert 16th-century Julian dates to the Gregorian calendar, add ten days. This would make their December 25 equivalent to our January 4.

- Carson, David - Children of the Sun: Following in the Footsteps of Narvaez and Cabeza de Vaca, Living Water Specialties, 2022.