Coronado Expedition Route Analysis

Coronado Expedition Route Analysis

- Introduction

- Overview of Coronado's Journey Through Texas

- Segment 1: From Tiguex to the Ravines

- Segment 2: From the Ravines to Quivira

- Segment 3: The Army's Return to Tiguex

- Segment 4: Coronado's Return to Tiguex

- Campo's Trek

- Summary

Next: Coronado Expedition Timeline

Introduction

This article analyzes the route that Spanish explorer Francisco Vázquez de Coronado took while leading his army across Texas in 1541. It is a continuation of the previous article, The Coronado Expedition in Texas, which gives a fuller explanation of Coronado's motives and a broader look at his expedition and its presence in Texas. This article focuses more on finding the specific places Coronado visited and the routes he took to get to them.

As the previous article explains, Coronado's trek through Texas began at Tiguex, near Bernalillo in present-day New Mexico. He crossed the open prairies of the Llano Estacado, being led - or misled, as the case may be - by an Indian guide. On the east side of the Llano Estacado, in a ravine that archeologists and historians have confirmed as Blanco Canyon, Coronado stopped for a while and reorganized his forces. Using a new guide, Coronado took a small company of horsemen to Quivira, in Kansas, and sent the rest of his army back to Tiguex. Coronado and his company later returned to Tiguex from Quivira along a different route than the one taken by the army. His journey, therefore, can be broken down into four segments:

- Coronado and his army's march from Tiguex to the ravines

- The march of Coronado and his small company from the ravines to Quivira

- The army's return to Tiguex

- Coronado's return to Tiguex

Some archeological evidence linking Coronado to specific sites in New Mexico and Texas has been found. The routes he took from one site to another, however, are open to interpretation. In conducting our analysis, we are guided by four written eyewitness accounts. The first account was written by General Coronado himself after his return to Tiguex. It is a letter written to Charles, the King of Spain, and was carried back by a captain who returned home from the expedition early. The next account, the anonymously-written La Relación del Suceso, or "The Account of the Event," was written either during the expedition or soon afterward from notes taken while on the journey. The other two accounts were written some decades later, one by a soldier named Pedro de Castañeda and the other by a soldier named Juan Jaramillo. Unfortunately, when it comes to matters such as distances traveled, time spent traveling, and direction, there is very little agreement among our primary sources. Our interpretation of Coronado's route, therefore, should be considered largely a historical exercise - an attempt to build a reasonable interpretation out of incomplete and sometimes conflicting information - rather than a historical proof.

Overview of Coronado's Journey Through Texas

The Coronado Expedition marched out of Compostela, on the west coast of present-day Mexico, in February 1540. Coronado traveled through northwestern Mexico, Arizona, and New Mexico and established a headquarters at a place on the Rio Grande called Tiguex, near present-day Albuquerque. Because this article is concerned exclusively with Coronado's journey through Texas, the route taken between Compostela and Tiguex is not part of this analysis.

The Texas-related leg of Coronado's expedition began in the spring of 1541. Coronado took his army out of Tiguex after the winter ice and snow thawed. The sources agree that he went in a generally eastward direction and came to some plains where there were huge numbers of bison. The writers, not having seen these animals before, referred to them as "cows." There were also nomadic natives called Querechos who hunted the bison and followed them across the plains. The prairie, which is now called the Llano Estacado, was remarkably flat and devoid of landmarks. Coronado's guide, who the Spaniards nicknamed "The Turk," took them all the way across the plains until they came out onto some ravines. There, some other natives called Teyas told Coronado that the land he was looking for, Quivira, was to the north, not to the east. Coronado realized that The Turk had been misleading him. He also began to doubt whether Quivira was the glorious land of gold and riches that The Turk made it out to be, but he still wanted to find it anyway. He decided to take a select company of about 30 horsemen to find Quivira and gave the rest of his army orders to return to Tiguex. A native named Ysopete guided Coronado's company to Quivira, in present-day Kansas. After spending a few weeks there, Coronado returned to Tiguex, where his army was waiting for him. The expedition returned to Mexico in mid-1542.

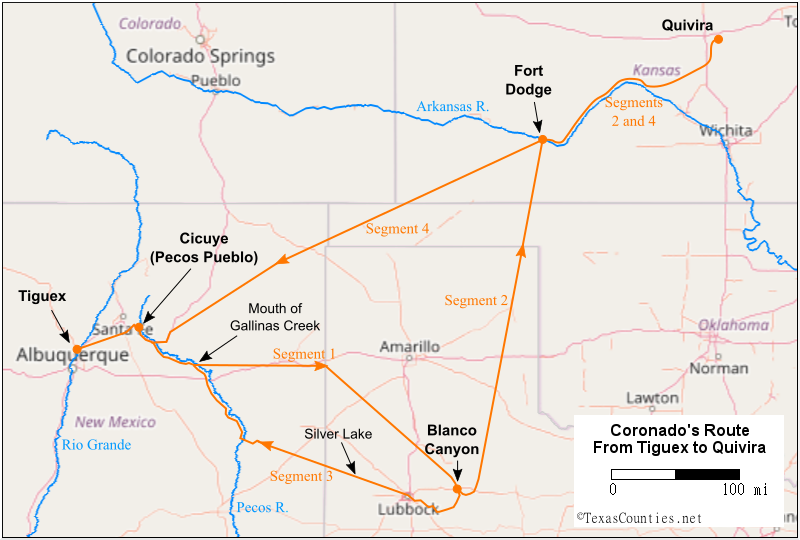

Our interpretation of Coronado's route from Tiguex to Quivira is shown in Figure 1, below. The following sections present our analysis of each segment of this journey.

Segment 1: From Tiguex to the Ravines

We begin our analysis of Coronado's journey from Tiguex to the ravines by examining some specific locations along the route that the expedition documents describe. Castañeda's account is the most detailed by far, but Jaramillo also includes some information about them.

Cicuye

The first destination Coronado and his army visited upon leaving Tiguex was a native village called Cicuye. This was an important village in the region, and one with which Coronado and his men had significant prior contact. In 1540, some leaders of Cicuye came to Cibola, in western New Mexico, to meet Coronado. Coronado had one of this captains, Hernando de Alvarado, go back to Cicuye with these men. It was at Cicuye that Alvarado met an Indian slave who the Spaniards called The Turk ("because he looked like one," Castañeda writes),1 who told them about the wealthy, gold-filled land of Quivira. Unfortunately, while the Spaniards were staying at nearby Tiguex for the winter, they accused the leaders of Cicuye of hiding gold from them and took them captive. In the spring of 1541, upon commencing his search for Quivira, Coronado went to Cicuye to return the native leaders to their people. He did not know at the time that the leaders of Cicuye conspired with The Turk to get Coronado and his men lost in their search for Quivira, as revenge for the Spaniards' shabby treatment of them.

Cicuye was in Glorieta Pass, which is near present-day Santa Fe between the Glorieta Mesa and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. This was a strategic location that connected the fertile, well-populated complex of villages along the Rio Grande with the nomadic bison hunters of the Great Plains. Subsequent generations of Spaniards sporadically occupied this village, which they called Pecos Pueblo, until the 1800s.

Like most of the other pueblos of New Mexico, Cicuye or Pecos Pueblo was made up of multi-story buildings. The natives lived and moved about on the upper levels, which were accessible from the ground by ladders and interconnected so that the inhabitants could walk from building to building without having to climb down to the ground. There were also several underground rooms called kiwas, which the natives used for meetings and ritual purposes. The Spaniards called them estufas, or stoves, because they were hot. The ruins of Pecos Pueblo, including a kiwa that visitors can enter, are preserved in Pecos National Historical Park.

To reach Cicuye from Tiguex, the expedition would have had to go around the north end of the Sandia Mountains. After that, it could have taken a route similar to modern Interstate Highway 25 to Glorieta Pass, or it may have taken a somewhat different route, but the terrain demands that it went through Glorieta Pass at the same location as I-25. It probably followed Glorieta Creek into Cicuye.

Castañeda wrote that Cicuye was 25 leagues from Tiguex.2 This note is helpful, for this is the only part of Coronado's route involved in this analysis where the expedition moved between two known waypoints along or fairly close to a known route. The distance between Bernalillo and Pecos Pueblo on I-25 is about 64 miles. There were two standards for the league used in the 16th century; the "common league," or legua común, of 4,000 paces, and the "statute league," or legua legal, of 3,000 paces.3 These two measures of the league equal 3.46 and 2.60 English miles, respectively. It appears that Castañeda used the shorter league, for 64 miles comes to 24.6 statute leagues, as opposed to 18.5 common leagues. The knowledge that Castañeda used statute leagues helps us to interpret Coronado's route in other places where the waypoints or the route between them is uncertain.

The Pecos River

Castañeda writes that four days after leaving Cicuye, the Spaniards had to stop and build a bridge across "a river with a large, deep current, which flowed down [from] toward Cicuye, and they named this the Cicuye river."4 This was the Pecos River, which flowed over a mile east of Pecos Pueblo. Jaramillo writes that the expedition reached this river three days after leaving Cicuye.5 He does not mention building a bridge to cross it.

This is the only record in any of the documents of a river on Segment 1. That fact, in and of itself, is quite helpful. The Pecos River is the only river that the expedition, regardless of the route it took, would have had to cross to get from Cicuye to the ravines on the east side of the Llano Estacado. About 60 miles downstream from Pecos Pueblo, the Gallinas River empties into the Pecos. If the expedition had crossed the Pecos upstream of that confluence, then it would have had to also cross one or more other streams, including the Gallinas River. Furthermore, if the expedition crossed the Pecos River upstream of the Gallinas River, it might have next encountered the Canadian or other rivers as it made its way east. If the army crossed the Pecos River below the mouth of the Gallinas, however, it had a clear shot all the way across the Llano Estacado, with no more rivers to cross, which is what the expedition chronicles suggest. This also makes more sense from a practical standpoint. In the early spring, the rivers were full of melted ice and snow running off the mountains. Crossing them was time-consuming and not without danger, so armies attempted to minimize the number of river crossings they had to make.

Jaramillo writes that the expedition "came to" the Cicuye or Pecos River three days after leaving Cicuye. This means the army stayed on the west side of it at first, probably following the base of the Glorieta Mesa along the route presently used by Interstate Highway 25. At present-day San Jose, where I-25 crosses the Pecos, the army must have stayed at the foot of the mesa. It must have turned more easterly at about Villanueva and come to the river some time before reaching Highway 84, then followed its west bank to somewhere below the mouth of the Gallinas River. It is about 55 miles from Cicuye to the confluence of the Pecos and Gallinas Rivers.

The Ravine Where It Hailed

Castañeda writes that eight days after crossing the river, the members of the expedition began to see "cows," i.e. bison, and two days after that, they met nomadic natives who were called Querechos. Some time later, while out on the open prairie of the Llano Estacado, they found a ravine with a small river at the bottom. The Spaniards and their company killed a large number of bison by chasing them into the ravine, where they fell and trampled over each other. After another four days, Coronado's men reached a large ravine where they rested. There, they were struck by a hailstorm that bashed their tents, broke their pottery, and wounded and scattered the horses. As explained in the previous article, The Coronado Expedition in Texas, a collection of Spanish crossbow points and other artifacts was discovered in Blanco Canyon between 1993 and 1996, and these discoveries have led archeologists and historians to conclude that this area was where the hailstorm occurred in 1541. The site is now known as the Jimmy Owens Site, named after the man who discovered the arrow points. It is in Blanco Canyon in southern Floyd County, south of the town of Floydada, near U.S. Highway 62. A Texas historical marker on Highway 62 marks the approximate location.

The route that the expedition took from the Pecos River to the Jimmy Owens Site cannot be determined from the incomplete and contradictory written records. Castañeda writes that for at least two days that the army was with the Querechos, it marched "between north and east, but more toward the north."6 His next indicator is that the advance guard found the small ravine where the bison were killed after being ordered to go "at full speed toward the sunrise for two days."7 Jaramillo writes that the army went "rather toward the northeast" to reach the Cicuye River, and after crossing it, "we turned more to the left hand, which would be more to the northeast."8 Later, Jaramillo writes, The Turk led them "more to the east."9 The Relación del Suceso does not give a breakdown of Segment 1, but it summarizes the entire segment as "150 leagues, 100 to the east and 50 to the south." This overall southeasterly bearing seems to contradict Castañeda and Jaramillo. The position of Blanco Canyon relative to Tiguex, Pecos Pueblo, and the confluence of the Pecos and Gallinas Rivers is east-southeast, so the Relación del Suceso appears to be more accurate on this point than Castañeda or Jaramillo. Even so, the Spaniards may well have marched northeast for part of the journey, for, as they were to discover, The Turk was deliberately trying to get them lost and confused and trying to get them and their horses killed or weakened from a lack of food and water.

Given these uncertainties, we can only guess which counties Coronado and his men visited on this segment. Perhaps they crossed the Texas-New Mexico state line in Deaf Smith County, although Oldham and Parmer Counties are also possibilities. Castro, Swisher, Lamb, and Hale Counties could all lay a reasonable claim to being along Coronado's route to Floyd County. It sounds like the expedition entered Blanco Canyon somewhere upward of the Jimmy Owens site, but exactly where cannot be ascertained. The best way for a modern person to get an overall sense of the trek across the plains is probably to follow U.S. Highway 84 from Santa Rosa, New Mexico to Lubbock.

The South End of Blanco Canyon

After the hailstorm, the army continued down Blanco Canyon and camped at a location where the ravine was "a league wide from one side to the other, with a little bit of a river at the bottom."10 The river is the White River (sometimes known as Blanco Creek), a tributary of the Brazos, and the location where Blanco Canyon opens up to several miles wide is near Crosbyton in Crosby County. Just south of here, the canyon widens even more and becomes part of the Caprock Escarpment, a ridge that defines the eastern boundary of the Llano Estacado. Here, the flat prairies suddenly drop some 300 to 1,000 feet and transform into rolling plains.

This location was apparently the furthest that the main part of the Coronado Expedition went from Tiguex and Cicuye. It was approximately 15 to 20 miles from the Owens site. After having spent some two weeks on the open plains, with little water and nothing but bison to eat, the army enjoyed a few days in the ravines of Blanco Canyon, where there were trees and a river and the men found nuts, berries, and fowl to eat.

All along the way from Cicuye, Coronado had been told by a native named Ysopete that Quivira was much less grand than The Turk had made it out to be, and furthermore, The Turk was taking him in the wrong direction. Coronado apparently began to have his doubts, because he stopped here to explore the country and look for other natives, having left the Querechos behind on the Llano Estacado. His men found some natives who they called Teyas. The Teyas knew where Quivira was and said it was to the north, whereas The Turk had been leading him southeast. Castañeda writes, "After this they began to believe Ysopete."11 Coronado consulted with his officers and decided to go with a select group of 30 horsemen 12 to go find Quivira, using Ysopete as his guide.

Coronado left a Captain Don Tristan de Arellano in command of the rest of the men in the ravine and ordered him to wait there for eight days, after which he would send messengers back with additional instructions.

The Distance of Segment 1

The sources give very different estimates of the total distance between Tiguex and Coronado's camp in Blanco Canyon. Castañeda stated that the distance was 250 leagues,13 while the Relación del Suceso gives the distance as 150 leagues.14 The actual distance along our interpretation of the route is about 380 miles, which equals 146 statute leagues. For the Relación to be so close not only lends credibility to our interpretation, but is also another instance of where the Relación appears to be a more reliable source than Castañeda or Jaramillo. It also indicates that, like Castañeda, the author of the Relación used statute leagues, not common leagues.

Segment 2: From the Ravines to Quivira

The best information about the journey that Coronado's small company of horsemen took from the ravines to Quivira is given by Jaramillo, who was a member of said company. He writes:

"And when everything was ready for us to set out and for the others to remain, we pursued our way, the direction all the time after this being toward the north, for more than thirty days' march, although not long marches, not having to go without water on any one of them, and among cows all the time."15

The company presumably left Blanco Canyon by going a bit further southeast and then commencing to ride northward along the base of the Caprock in Dickens and Motley Counties. There are numerous seasonal creeks along this route that collect the rainfall coming off the Llano Estacado, as well as some larger rivers, including Middle Pease River, North Pease River, Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River, Salt Fork Red River, North Fork Red River, Canadian River, and Beaver River. There would have been no need for the Spaniards to follow the rugged Caprock as it curved to the west toward Amarillo, and certainly no need for them to enter Palo Duro Canyon. Instead, their Teyas guides probably took them on a more north-northeastward path through Hall County.

Caprock Canyons State Park in Briscoe County is probably too far west to have been on Coronado's path, but it nevertheless provides visitors a good example of the kind of terrain the men would have seen for the first few days after separating from the main army. This park is also home to the Texas state bison herd, which reportedly numbered over 100 animals in 2018. The herd is made up of the descendants of a few animals that belonged to rancher Charles Goodnight, who saved them from extinction.

On St. Peter and Paul's Day - June 29 - Coronado's company came to a river, crossed it, and followed its north bank northeast toward Quivira. Historians have generally taken this river to be the Arkansas, and the crossing to be at a ford in the river near present-day Fort Dodge, Kansas, east of Dodge City. A 38-foot cross, the "Coronado Cross," was erected in June 1975 at Fort Dodge to commemorate the crossing.

Other than Jaramillo's notation that the country the company of horsemen passed through had plenty of bison and sources of water, none of the accounts describe what they saw between the ravines and the river crossing. Despite the statement in the Relación del Suceso that the march from the ravines to the river went "by the needle,"16 i.e., due north, the men had to have veered to the north-northeast to cross the Arkansas River at Fort Dodge. If we accept this as the correct crossing - and we do - then they passed through at least three of the four counties north-northeast of Hall County: Donley, Collingsworth, Gray, and Wheeler. Coronado's men may have traversed a part of Roberts County before leaving Texas, most likely through Hemphill and Lipscomb Counties. A modern traveler could probably see some of the same country Coronado saw by using U.S. Highway 83.

Like most other parts of Coronado's journey, his route after crossing the Arkansas River is open to interpretation. The most commonly-held view is that he followed the north bank of the Arkansas River downstream for a long way, past the so-called "Great Bend," then left the river where the bend turned to the southeast. He crossed Cow Creek in the vicinity of Lyons, Kansas and followed the Smoky Hill River to present-day Salina. This route is about 175 miles long - the first 100 of it or so on the north bank of the Arkansas River, and then another 75 miles across to Salina. This interpretation is corroborated by the Relación del Suceso's statement that the "river Quivira" was 30 leagues below the settlement.17 30 statute leagues equals 78 miles.

The total distance Coronado traveled from Tiguex to Quivira, according to our interpretation, was about 855 miles, or 329 statute leagues. This accords amazingly well with the Relación del Suceso's estimate of 330 leagues.18

Segment 3: The Army's Return to Tiguex

A few days after Coronado left, his messenger returned to the army at Blanco Canyon with orders for it to return to Tiguex. Instead of leaving immediately, however, Castañeda writes that the army spent "a fortnight" in the ravine, using this time to wait on some messengers to return and to make beef jerky to take with them.19

Some Teyas guides led Coronado's army back toward Tiguex. Under their efficient guidance, the army took less time going west than it took to go east, when it was being guided by the deceptive "Turk." Castañeda writes that the army covered in 25 days what had earlier taken 37.20 Segment 3 also took a more southerly route than Segment 1, perhaps because the Teyas wanted to steer clear of their enemies, the Querechos. Castañeda writes that the army reached the Cicuye (Pecos) River more than 30 leagues below the bridge they had built, which was presumably near the mouth of the Gallinas River. This would place their arrival at the Pecos River probably in De Baca County, New Mexico, either at or below Fort Sumner, which is where the course of the river bends from southeast to south. The army could have even hit the Pecos River as far south as Roswell in Chaves County. Their Teyas guides informed them that "this river joined that of Tiguex (i.e., the Rio Grande) more than 20 days from where they were, and that its course turned toward the east."21 It is some 400 miles from Roswell to the confluence of the Pecos River and the Rio Grande, and a further 80 miles from Fort Sumner. Both locations, or anywhere in between, could be expressed as "more than 20 days" away.

Castañeda does not say how the army left Blanco Canyon, but considering the fact that the Teyas led the men mostly to the west, rather than the north, it seems highly possible that they came all the way out of the mouth of Blanco Canyon, turned west, and then followed the North Fork Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos River through Yellow House Canyon in Lubbock County. They would have emerged back out onto the Llano Estacado in the present-day city of Lubbock. It is conceivable that they crossed the edges of Garza and/or Lynn Counties.

Castañeda writes that on the way to the Pecos River, "They found many salt lakes on this road, and there was a great quantity of salt. There were thick pieces of it on top of the water bigger than tables, as thick as four or five fingers."22 On the south side of one of these salt lakes was an enormous heap of cow (bison) bones, "a crossbow shot long, or a very little less, almost twice a man's height in places, and some 18 feet or more wide."23 Castañeda writes, "there are no people who could have made it" and theorized that old or weak cattle went into the lake to get water, were unable to get out, and died, and then the north winds created waves that pushed the bones to the south side of the lake.

A Pleistocene-era bonebed known as the Silver Lake Bison Site matches Castañeda's account. It is at Silver Lake, at the northern end of the Cochran-Hockley County line. This location is about 50 miles west-northwest of Lubbock, and is along the general line of travel that the army probably took between Blanco Canyon and the Pecos River. Assuming the Silver Lake Bison Site is the boneyard Castañeda saw - and this is not a settled historical issue, but only a theory - then the army passed through Lubbock, Hockley, and Cochran Counties and then crossed the Texas-New Mexico State Line in either Cochran or Bailey County.

Silver Lake is on private property. Any local roads leading to it that one may see on maps are either closed to the public or do not actually exist.

After the army came to the Pecos River, it followed it up to the village of Cicuye. Castañeda does not describe this portion of the journey at all, but it is safe to assume that the men passed through the sites where the towns of Fort Sumner and Santa Rosa now exist. Castañeda writes that the natives of Cicuye, who hoped they would perish on the plains, were unfriendly and "ready for war."24

The final leg of the journey was from Cicuye to Tiguex. Castañeda writes that some of the natives of Tiguex had returned to their homes while the Spaniards were gone. When the Spaniards came back, they left again, out of fear.

The length of the route the army took back to Tiguex, using our interpretation, is about 400 miles. This is actually slightly longer than our interpretation of the army's route going east, which is 380 miles, but it has the army walking for a substantially shorter distance on the dry, treeless plains of the Llano Estacado. This is probably what Castañeda meant in saying that the army went back to Tiguex on "a more direct road."

Segment 4: Coronado's Return to Tiguex

Coronado and his company arrived at Quivira in July. Coronado found that The Turk's stories about it being a land of gold and treasure were lies. There was no gold, silver, or jewels - only some copper, and that appeared to have come from somewhere else. The Turk confessed that he had lied to the Spaniards and said that the natives of Cicuye had urged him to do so, so that they would get lost on the plains and either die or return so weak they would be easy to kill. Coronado then had The Turk strangled in his sleep.

Coronado and his men explored the country of Quivira, visiting several villages. They saw that the land was very fertile and had a good climate, and they determined that it would be a good place to establish a settlement. They made plans to return to Tiguex to rejoin the army and spend the winter there. In the spring, a large group would march back to Quivira with the intention of starting a colony. When Coronado was ready to leave, his guide, Ysopete, asked if he could stay in Quivira as a reward for his faithful service to him. Coronado granted his request.

Some natives from Quivira guided Coronado and his men back to Tiguex. According to Jaramillo, they retraced their route back to the location identified in a previous section as Fort Dodge, on the Arkansas River. There, instead of going south, they turned to "the right hand," i.e., west, and went along "a good road" that had watering places and bison.25 We know from this that Coronado took a more westerly route from the Arkansas River to Cicuye than the one he had taken to get there, and we know from the Relación del Suceso that it was a much shorter trip. If the distances given in the Relación are accurate, Coronado traveled 330 leagues to get to Quivira, but only 200 leagues to get back.

In the 1800s, American pioneers developed the Santa Fe Trail, a transportation route that extended the old Spanish camino real that went from Mexico City to Santa Fe into the American heartland. The Santa Fe Trail passed through Dodge City, Kansas, which is west of Fort Dodge and would have been on "the right hand" of someone coming from Quivira. We do not know whether the Santa Fe Trail used any of the trail traveled by Coronado, but nevertheless, looking at the route of the Santa Fe Trail can be helpful in understanding Coronado's journey, since the goal of establishing a major overland travel route is always to find the easiest, safest, and fastest way.

There were two routes of the Santa Fe Trail between Dodge City and Santa Fe in the 1800s. The mountain route, which was longer, but had more access to water, followed the Arkansas River as far as present-day La Junta, Colorado. It then broke south, following a route that is now approximated by U.S. Highway 350 to Trinidad on Interstate 25. The shorter, but drier, Cimarron route took a path approximated by U.S. Highway 56 to Springer, also on Interstate 25. Both routes entered Santa Fe on present-day I-25 by way of Las Vegas, New Mexico. Neither route crossed present-day Texas.

In this day of modern highways, access to sources of water is not a concern, and engineers are more able to deal with difficult terrain, so it is possible to design roads that are straighter and more direct than those built in the 1500s or 1800s. Even so, the shortest route from Dodge City to Santa Fe, U.S. Highway 56, still does not go through Texas, save for literally a few square feet of the state's extreme northwest corner in Dallam County. A relatively direct route between Dodge City and Santa Fe does exist with U.S. Highway 54, which passes through Sherman, Dallam, and Hartley Counties. It is longer than the Highway 56 route, however, and it also bears pointing out that Highway 54 does not take "the right hand" after crossing the Arkansas River, but instead goes due south.

In conclusion, we do not know how Coronado went from Quivira to Cicuye, and so we do not know whether he passed through any part of Texas on Segment 4. It is possible that his party took a route that went below Highway 56 and passed through some of the Texas Panhandle area. We do know, though, that Coronado had good guides and the trip went relatively quickly. In the 1800s as well as in the present day, people traveling between roughly the same points that Coronado did with a goal of getting to their destinations quickly and efficiently have not gone through Texas. Our best guess, therefore, is that Coronado did not either.

Castañeda writes that Captain Arellano, who was in command at Tiguex, became anxious because Coronado and his men were overdue in returning from Quivira. He took 40 men with him to Cicuye, where the natives came out to do battle. The Spaniards killed a few of them, and they retreated to their village. At about that time, word arrived that Coronado was on his way to Cicuye and was close. Arellano waited for him, and then they all went back to Tiguex together.

According to our interpretation, the total distance from Quivira to Tiguex was about 610 miles, or 234 statute leagues. According to the Relación del Suceso, however, the return trip to Tiguex was "not more than 200" leagues long.26 This discrepancy of 17 percent is not huge, but it is larger than usual, especially for the generally-reliable Relación. There does not appear to be any way for the route to be any shorter than we have made it, however, so either the author of the Relación is mistaken on this point, or perhaps he counted the return trip as beginning at the great bend of the Arkansas River, the boundary of the "province of Quivira," rather than at the settlements.

Campo's Trek

When the spring of 1542 came, Coronado called off his plans to attempt to go back out to Quivira to place a colony there. Instead, he took his expedition back to Mexico by the same way it came - through Cibola in western New Mexico, the Sonora River valley, and the towns of Culiacan and Compostela. Coronado and his captains never saw Texas again, but a few members of the expedition chose to stay behind, and some of them did travel through Texas one more time.

When Coronado was leaving, Friar Juan de Padilla, who had been part of the company that Coronado took to Quivira in 1541, expressed a wish to return there so that he could evangelize the natives of that province. As usual, the surviving first-hand accounts of the expedition offer some conflicting information, but what can be ascertained is that up to five people went with him, including a Portuguese soldier named Andrés do Campo, and that the others were of black, Indian, and/or mixed races. Somewhere in the province of Quivira, Padilla and his group met resistance from the natives. Padilla was killed. Campo fled on horseback. Some of the attendants either fled in a different direction or were captured. Years later, Campo and two of these other men arrived together at Panuco, on the Gulf coast of Mexico, near present-day Tampico.

To pass from central Kansas to Panuco, Campo and his companions must have crossed through a large swath of Texas, but there is only one hint as to his route - a statement by Castañeda that Campo "came to cross the North Sea mountain chain," but "he did not see the river of the Holy Spirit at all."27 At this time, Spain viewed the geography of the present-day United States as consisting of the "South Sea," or Pacific Ocean, and its mountains; the "North Sea," or Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, and its mountains; and the plains in between. Castañeda's account indicates that Campo went south or southeast from Quivira, but never went as far as the Mississippi River, which Spain at that time called the "River of the Holy Spirit." He did, however, cross through some mountains on the west side of the river. These would be the Ozark, Ouachita, or other mountain ranges of Arkansas and/or western Oklahoma. Neither Castañeda nor any other historian mention that Campo saw the "North Sea." We can conclude from this that he traveled through the eastern half of Texas. We have no way of knowing, however, whether he crossed the Red River in the vicinity of, say, Wichita Falls then went in a relatively straight north-to-south path to cross the Rio Grande, or whether he veered southeast, crossed the Red River maybe around Texarkana and then veered back southwest. It does not seem likely that he went southwest from Quivira, crossed the Red River west of Wichita Falls, and then went back to the southeast across Texas, for in doing that, he would have missed the "North Sea mountain chain" completely.

Since Campo's route is unknown, a county-by-county interpretation of it cannot be projected. His trek, therefore, is not included in the summary below.

Summary

If our exercise in analyzing the Coronado texts and other geographical and historical information is accurate, then Coronado and his men may have visited up to 26 counties in northwestern Texas. The likelihood that they visited each of them is estimated as follows:

- Very likely to certain: Crosby, Floyd

- Probable: Bailey, Castro, Cochran, Deaf Smith, Dickens, Donley, Gray, Hale, Hall, Hemphill, Hockley, Lipscomb, Lubbock, Motley, Swisher, Wheeler

- Possible: Collingsworth, Dallam, Garza, Lamb, Lynn, Oldham, Parmer, Roberts

An interactive map showing our interpretation of Coronado's route with county lines superimposed on it is provided in Figure 13.

Our next article constructs a proposed timeline for this route.

By David Carson

Page last updated: September 25, 2018

1Castañeda, p. 492.

2Castañeda, p. 503.

3Spanish expeditions kept track of the distances marched by assigning one man to count his steps. See Castañeda, p. 508.

4Castañeda, p. 504. Although this article uses Winship's translation, Winship errs in translating que baxaba de hacia cicuye as "flowed down toward Cicuye." Hammond and Rey's translation, "from the direction of Cicuye," is more accurate.

5Jaramillo, p. 587.

6Castañeda, p. 504.

7Castañeda, p. 505.

8Jaramillo, pp. 587-588. As with many of Jaramillo's recollections, he qualifies this one by saying, "If I remember rightly."

9Jaramillo, p. 588.

10Castañeda, p. 507.

11Castañeda, p. 507.

12This is per Coronado, p. 581, the Relación del Suceso, p. 577, and Jaramillo, p. 589. Castañeda, p. 508, writes that the company consisted of "thirty horsemen and a half dozen foot-soldiers." Regardless, the actual number of persons in the company was higher, for it definitely included Ysopete, The Turk, Friar Juan Padilla, and doubtless several other guides, servants, helpers, and support personnel, who the chroniclers always tend to ignore in their enumerations.

13Castañeda, p. 508.

14Relación del Suceso, p. 577.

15Jaramillo, p. 589.

16Relación del Suceso, p. 577.

17Relación del Suceso, p. 577.

18Relación del Suceso, p. 578.

19Castañeda, p. 508.

20Castañeda, pp. 509-510.

21Castañeda, p. 510

22Castañeda, p. 510.

23Castañeda, p. 542.

24Castañeda, p. 510.

25Jaramillo, p. 591.

26Relación del Suceso, p. 578.

27Castañeda, p. 544.

- Anonymous - "Relacion del Suceso" - translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C. 1896

- Castañeda, Pedro de - "The Narrative of Castaneda," translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C., 1896

- Coronado, Francisco Vazquez - Letter to King Charles written October 20, 1541, translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C., 1896

- Jaramillo, Juan - "The Narrative of Jaramillo," translated by George Parker Winship, The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542, Washington, D.C., 1896