The De Soto-Moscoso Expedition in Texas

The De Soto-Moscoso Expedition in Texas

- Introduction

- Sources

- De Soto in the Southeastern U.S.

- Moscoso Takes Command

- Outline of Moscoso's Expedition

- Analysis

- On the Gulf of Mexico

- Conclusion

Next: De Soto-Moscoso Expedition Personnel

Introduction

In 1539, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto brought an army to Tampa Bay, Florida with the goals of finding gold and other wealth and establishing a permanent Spanish colony on the American mainland. He then took his men on a years-long trek across what would become nine states in the southeastern United States, in hopes of stumbling upon a grand native city of riches and splendor. He succumbed to illness and died on the Mississippi River in 1542. His second-in-command, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, then took command of the expedition. Moscoso abandoned De Soto's goals and made getting back to Spanish civilization his main priority. In an attempt to lead his men to Spain's province in present-day Mexico, he explored Arkansas and/or Louisiana and entered Texas. After spending some time marching through east Texas, he changed his mind about walking to Mexico and took his men back to the Mississippi River. There, they built ships, took them down the river, and sailed along the Texas coast to Mexico. This article examines the De Soto-Moscoso Expedition's activities in present-day Texas in 1542.

Sources

There are three primary sources on the De Soto Expedition, but one of them is missing the pages that deal with the Texas segments of the journey. The earliest of the two sources useful to us is a first-hand account written by Luis Hernández de Biedma, a royal official on the expedition. He wrote his account in 1544, soon after his return to Spain. Our other primary source is a first-hand account written by an anonymous Portuguese member of the expedition who published in 1557 under the name, "A Gentleman of Elvas." Of the two, D'Elvas's account is longer and more detailed. Biedma's though sketchier, has the advantage of being written from a fresher memory.1

De Soto in the Southeastern U.S.

De Soto, having been appointed governor-general of Florida by King Charles, launched his expedition from Spain. After spending the better part of a year in Cuba, he sailed to Florida in May 1539. He disembarked on the south shore of Tampa Bay on May 30, 1539 with over 600 men and 200 horses. Like his predecessor in Florida, Pánfilo de Narváez, De Soto was told by natives that the wealthiest, most abundant province in the country was at a place called Apalache, which was at present-day Tallahassee. De Soto took his men and ships to Apalache and spent the winter of 1539-1540 there. But Apalache was not the grand city of gold he was looking for. He set out from there and went northeast, through Georgia and South Carolina, then on a highly circuitous westward journey through North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas, never being content with what he found. His treatment of the natives was abominable; his standard practice was to kidnap the chief of any town he visited and demand that he or she provide his army with guides, interpreters, porters, and female companions to the next town. When natives resisted him, he made war on them, and when they angered him in some way, he cut off their noses, cut off their arms, threw them to his dogs, or burned them alive. On rare occasions, natives would submit to him, but that was usually a ploy to use him as an ally to make war on their neighbors.

De Soto reached the Mississippi River in May 1541. There were several towns on it, so he spent some time there. He then moved westward nearly as far as Oklahoma, but then decided there was no point in going further west. Anxious to find the ocean so that he could build ships and restore contact with the outside world, he returned to the Mississippi River in southeast Arkansas. There, he became sick. Knowing he did not have long to live, he nominated his second-in-command, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, to become the new governor. The men then elected Alvarado as their leader, and De Soto died. Moscoso initially had him buried, but then decided that before continuing on, it would be better to exhume his body and dispose of it in the Mississippi River.

Moscoso Takes Command

With De Soto gone, there was little interest on Moscoso or anyone else's part in continuing to wander aimlessly around the continent looking for a grand native village to rob of its gold. The men, whose numbers had been reduced nearly by half from conflicts with natives, desertion, illness, and mishaps, only wanted to get out of La Florida alive. They were not sure, however, that the Mississippi River was their best way out. They did not know how far they would have to travel on it and whether there would be waterfalls or other such dangers. Furthermore, they knew that once they exited the river and entered the Gulf of Mexico, it was a long way to Panuco, the closest Spanish town on the coast. They also knew that if they walked southwest, they would eventually reach Mexico, which was then called New Spain. Moscoso obtained signed statements from his officers and captains declaring that they wished to walk to New Spain.

Outline of Moscoso's Expedition

While Biedma and D'Elvas often disagree on some details and present a few facts out of order from each other, it is still nevertheless possible to produce an outline of Moscoso's journey from the Mississippi River into Texas:

- West of the Mississippi River, the expedition came to a country where the natives produced salt. D'Elvas calls it Chaguate and dates Moscoso's arrival as June 20, fifteen days after leaving the Mississippi River. Biedma calls the salt land Chavite and records the time from the Mississippi River as seventeen days.

- West of Chaguate/Chavite, the expedition came to Aguacay. D'Elvas writes that there was also salt at Aguacay, and it was not far from a salt lake. He does not estimate the travel time from Chaguate, but eight days fits other parts of his timeline. Biedma states that Aguacay was three days "directly westward" from Chavite.

- The next town the texts agree upon is called Nisione or Nissoone. D'Elvas writes that between Aguacay and Nissoone, there was a large river that was too swollen to cross, even though it had not rained for a month. The natives told Moscoso that this happened frequently. Eight days later, Moscoso crossed the river. There was a town called Naguatex on the west side of it. D'Elvas accounts for about sixteen days of travel from Aguacay to Naguatex and three days from Naguatex to Nissonne. Biedma only writes that the expedition had been going "directly west" to Aguacay, then was advised by the natives there to change directions to the south. He does not estimate the travel time, nor does he mention the river or Naguatex.

- The expedition next went through two towns, one of which was called Nondacao. D'Elvas writes that the second town was four days from Nissonne. The two writers agree that their guides deliberately tried to get them lost for part of this segment, although they disagree about which part, and which of the two towns was Nondacao.

- While being guided to a town called Soacatino/Xacatin, they passed through Aays (D'Elvas) or Hais (Biedma). In both sources, Aays/Hais is the third town from Nisione/Nissoone. D'Elvas writes that it was five days from the last town.

- The town after Aays/Hais was Soacatino (D'Elvas) or Xacatin (Biedma). Both accounts describe it as having little food. Biedma writes that it was in dense woods. D'Elvas writes that the expedition was led out of the way again getting there.

- The two accounts break away from each other here. D'Elvas writes that about twenty days from Soacatino, they came to Guasco. The natives began feeding them rumors about seeing other "Christians," i.e., Europeans, and the expedition went to towns including Naquiscoza and Nazacahoz searching for them. When they realized the natives were pulling their legs, they returned to Guasco. Biedma writes that they went east from Xacatin and followed rumors of other Christians, then went six or seven days south-southwest.

- D'Elvas writes that ten days west of Guasco was a river called Daycao. The natives of Guasco knew little about what was on the other side. Moscoso sent ten horsemen out. They crossed the river, captured two natives, and brought them back. Those natives and the natives of Guasco could not understand each other. Biedma merely writes that ten horsemen were sent to go 8 or 9 days to look for another town. They brought back some natives that could not be understood. It was at that point that Moscoso and his men decided to turn the expedition around.

- Both accounts skip over the return journey to the Mississippi River except to say that the expedition retraced its steps to get there.

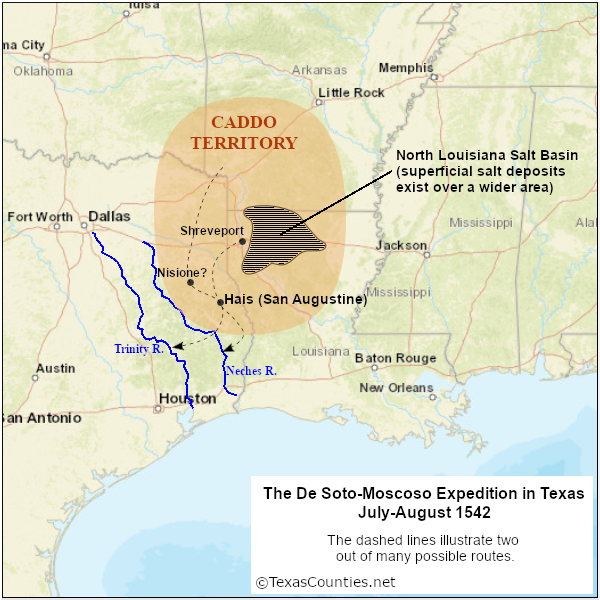

The general area Moscoso and his men explored can be determined easily enough from this outline. Underground salt domes are prevalent throughout east Texas, south Arkansas, and the entire state of Louisiana. These salt formations pierce the surface at numerous places, especially in north-central Louisiana. There is ample archeological and historical evidence showing that natives from Caddo and other tribes worked these salt deposits, producing salt for trade and export. Many of the towns mentioned in the texts - Nisione/Nissoone, Naguatex, Aays, Nazacahoz, etc. - match or closely resemble the names of Caddo clans. The dense woods mentioned in the texts are another hallmark of the so-called "Ark-La-Tex" region.

Analysis

A common mistake when attempting route analysis is to start at the first place mentioned in the texts and work forward from there. This approach works when the waypoints, directions, and distances are clear to begin with, but when they are not, it is easy to misidentify the first waypoint and then spend the rest of the analysis justifying that first bad choice. Moscoso's route is especially vulnerable to this pitfall, since there are so many superficial salt deposits in our study area. It is better to start with the waypoints and features that are the easiest to identify and extrapolate the other parts of the route from them.

We begin with the town that D'Elvas calls Aays and Biedma calls Hais. This is clearly the territory of the natives that subsequent Spanish explorers called Ais and Anglo settlers called Ayish.2 Some historians believe that the Ais Indians were part of the Caddoan confederacy, while others believe they were independent and had their own language, but also spoke Caddo. Regardless, they were a small clan and were only ever known to inhabit one location: the vicinity of the present-day town of San Augustine, Texas. In 1717, Spanish Franciscan missionaries built a mission to the Ais. The mission stood near the center of a cluster of about eight Ais settlements scattered within a five-mile radius. The site near downtown San Augustine has been preserved, even though the mission no longer exists. The stream running west of San Augustine and the mission was subsequently given the name Ayish Bayou.

The next step is to identify the two rivers mentioned in the texts. The first river was too swollen to cross for eight days, even though it had not rained for a month. The natives stated that this happened regularly. This means the river was carrying floodwaters from a great distance upstream. In other words, it was a long river that drained a large area. To get to San Augustine from the east, the expedition would had to have crossed two large rivers - the Red and the Sabine. The Sabine River would have been crossed about 170 miles below its headwaters, while the Red River would have been crossed more than 700 miles below its headwaters. The Red River's basin is more than six times larger than the Sabine's. The most logical conclusion is that the river between the salt fields and Hais was the Red. Furthermore, the distance the expedition covered from the river to San Augustine seems to fit better if the swollen river is the Red.

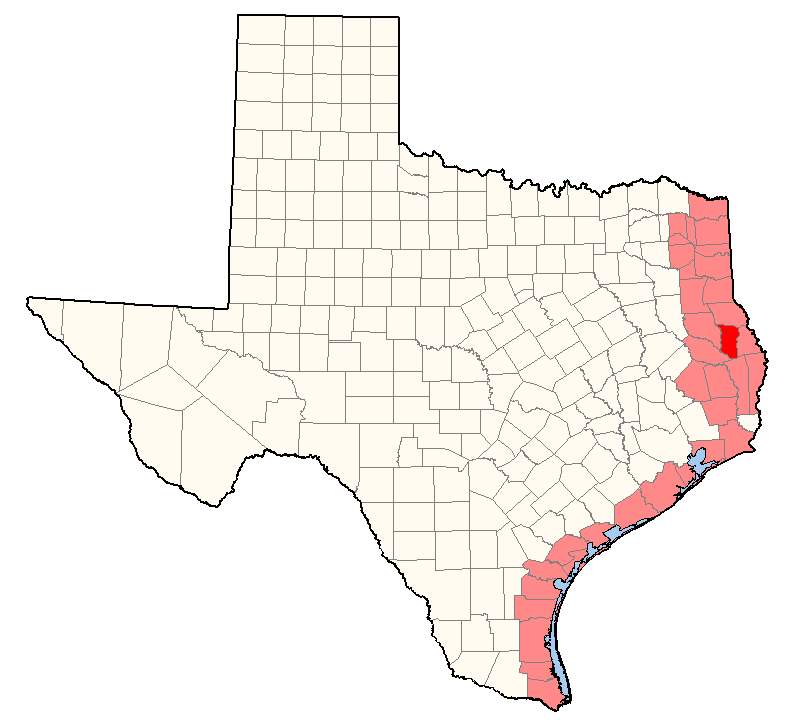

The other river, which D'Elvas calls the Daycao, took several weeks to reach after leaving Hais. D'Elvas indicates it took nearly a month, while Biedma implies closer to three weeks. Both writers state that some of this time was wasted with following rumors of other Europeans in the area. That river was the farthest location that the expedition reached. Its identification is one of the main points of disagreement among Moscoso route analysts, with the Neches, Trinity, and Brazos being the ones most commonly named. Many analysts base their selection of rivers only on their estimates of how quickly the expedition traveled and how far it could have gotten in a given time frame. There is, however, a more important piece of information that both D'Elvas and Biedma share with us and we would be remiss not to consider: this river served as a language boundary between the tribes on its east, who we now know as the Caddo, and those on its west. This excludes the Brazos, which was well outside Caddo territory. The actual limits of Caddo territory are difficult to determine because early maps always have serious problems with scale and accuracy, but nevertheless, there is ample archeological and historical evidence indicating that the Caddo were spread throughout northeast Texas up to the Neches River, as shown in Figure 1. Additionally, Spaniards and French in the 17th and 18th centuries were known to have had some interactions with Caddo as far as the Trinity River, but no further. The Caddo only crossed the Trinity to go to war.

Using the above findings that the Moscoso expedition crossed the Red River, passed through San Augustine, and turned back at either the Trinity or Neches River, we now proceed to extrapolate more of its route. Knowing the location where the expedition crossed the Red River would be helpful. D'Elvas tells us that a town called Naguatex was on the west side of this river. Aays/Hais was at least twelve days beyond it. There were three towns in between Naguatex and Aays: Nissoone, Lacane, and Nondacao. The expedition came through Aays while on the way to Soacatino. Biedma does not mention Naguatex or the river, but he does mention three towns on the way to Hais: Nisione, Nondacao, and Came. Significantly, Biedma tells us that the natives of Aguacay, which was back on the salt flats, advised the expeditionaries to turn south.

The names Nissoone/Nisione and Nondacao clearly relate to the Caddo clans called Nazoni and Nadaco. In the early 18th century, these clans lived in between the Angelina and Sabine Rivers in south Rusk and Panola Counties. In 1716, Spain built a mission to the Nazoni in extreme north Nacogdoches County, near the Nacogdoches-Rusk County line. The Nazoni and Nadaco were so closely related that people in the 18th century sometimes considered them to be two names for the same clan. There is some confusion in the texts about which direction the expedition was going on the way to Nazoni, but seeing as the men had been advised not to go west, and their goal was Mexico, a direction between south and southwest can be assumed.3 Extending a line from the Nazoni mission to the Red River in every plausible direction results in a crossing somewhere between Shreveport and the general vicinity of Texarkana.

Both texts mention that, when it went from Nisione to Hais, the expedition was on its way to Soacatino/Xacatin. Thus, the men were no longer necessarily going in the same direction by which they reached Nazoni. If our waypoints for Nisione and Hais are correct, Soacatino was southeast of Hais. The expedition appears to be approaching the Sabine River again. From there, the records become even sketchier. Biedma writes that the expedition went east from Xacatin, did some wandering, then went south-southwest, then rode 8 or 9 days until they found natives who spoke an unknown tongue. D'Elvas mentions towns named Naquiscoza, Nazacahoz, and Guasco and states that the river where the expedition ended was ten days west of Guasco. The names Naquiscoza and Nazacahoz sound Caddoan, but do not correspond with any known clan. The names Xacatin and Guasco are unknown. Even without the texts' declarations that the expedition is near a native language boundary, the toponyms hint to that effect. The Caddo did not occupy all of east Texas; only the upper two-thirds of it. Present-day San Augustine County was about as far south as they lived. Therefore, when Moscoso and his men went south or southeast of San Augustine - or even if they went southwest - they would have soon been out of Caddo territory and in a country where the Caddo language was not spoken.

Because of the poor, somewhat contradictory nature of the texts descriptions of the expedition's movements past Soacatino, it is impossible to identify the river Daycao, where Moscoso decided to turn the expedition around. As noted above, it could not be the Brazos, for this river is well beyond the area of Caddo influence. The two other rivers that are usually proposed are the Trinity and the Neches. If we lean toward Biedma's account and interpret the expedition going mostly south or southeast after leaving Hais, then the Neches would be the most likely choice. D'Elvas seems to have the expedition moving more westerly, however, which could have gotten it to the Trinity.

On the Gulf of Mexico

Moscoso successfully led his men back to the Mississippi River. There, they spent the winter and spring building seven small ships. They sailed down the river for 17 days and entered the Gulf of Mexico on July 18, 1543. At first, they intended to follow the Gulf coast as it curved from westward to southward. One of the officers then convinced Moscoso to attempt to sail straight across the Gulf to save time. When the little ships began running out of fresh water, however, they gave up on this plan and returned to the coast. As they made their way down the coast, the ships entered a bay, then, further on, a sheltered creek, then an "arm of the sea" that was about six miles long and infested with mosquitos, then another bay or arm of the sea that seemed endless, then past an island into another arm of the sea. After that, they sailed to Panuco, without any other geographic features being mentioned. The men were obviously exploring the barrier islands and long, narrow sheltered bays that characterize most of the Texas coast, such as Padre Island and the Laguna Madre. It is hard to tell where this coastal exploration may have started, but seeing as how the texts mention four of these bays, it seems that they must have started at least at Matagorda Bay, if not Galveston Bay. Where they might have landed to draw water or camp is impossible to determine.4

Conclusion

The records of the De Soto Expedition make it clear that Luis de Moscoso Alvarado led the remnants of De Soto's men from the Mississippi River through the salt-producing district of north Louisiana and/or south Arkansas before crossing the Red River and entering Texas. They went mostly southward - not westward, as many route interpreters conclude - through Caddo territory and passed through present-day San Augustine. Beyond there, they may or may not have changed directions to go more westerly. They halted when they reached a river where the natives could not communicate with the natives who had been guiding them. They then retraced their steps to the Mississippi River. While the popular conclusion that the river where Moscoso turned around was probably the Neches or the Trinity seems sound, there simply is not enough information given in the texts to interpret a specific route for the Texas segment of the De Soto Expedition. As Figure 2 shows, it is possible that Moscoso and his men visited any of twenty east Texas counties, in addition to San Augustine County, along with any of fourteen counties along the Gulf coast.

By David Carson

Page last updated: October 12, 2022

1Many writers use a fictionalized history of Florida written by Garcilaso "El Inca" de la Vega in 1605 as a source on the De Soto Expedition, but they shouldn't. Vega's "history of Florida" is no more of a source on the De Soto Expedition than John Wayne's The Alamo is a source on the Battle of the Alamo.

2In Spanish, "Aays," "Hais," and "Ais" are all pronounced identically: AH-ees.

3Different English translations disagree as to whether the direction the natives of Aguacay recommended was "southwest and by south" or "southeast." Furthermore, Biedma does not state how well their directions were followed, and both sources relate how their guides tried to get them lost.

4Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and other members of the Narváez Expedition had previously traveled the Texas coast from 1528 to 1534 and had many encounters with natives, but the De Soto Expedition texts do not mention whether Moscoso's men met any natives on the coast.

- Biedma, Luis Hernandez de - "Account of the Island of Florida", translated by Buckingham Smith, in The De Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539-1543, Volume I, University of Alabama Press, 1993.

- (A Gentleman of) Elvas - A Narrative of the Expedition of Hernando de Soto into Florida, translated by Richard Hackluyt, 1609.

- John R. Swanton, "The Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission," January 8, 1939.

- Texas Beyond History, Who Were the Ais?, accessed on August 9, 2022.

- Texas Beyond History, Caddo Ancestors, accessed on August 9, 2022.