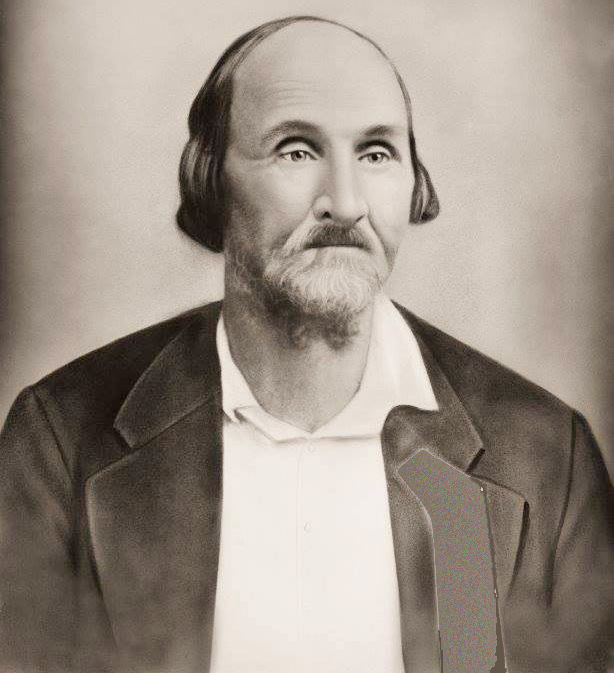

Andrew J. Sowell

Andrew J. Sowell

A Courier From the Alamo

A grave marker in San Geronimo Cemetery in Seguin reads:

ANDREW JACKSON SOWELL

JUNE 27, 1815 - JAN 4, 1883

ALAMO SURVIVOR - TEXAS RANGER

INDIAN FIGHTER

REPUBLIC OF TEXAS PATRIOT

LUCINDA'S "OLD WARRIOR"

Alamo survivor? Hmm ... The original story of the Alamo was that all of the men who fought there were killed, and that the only survivors were women and children. It is true, though, that in more recent times, historians have proposed that there were a few surviving combatants. Was Andrew Jackson Sowell one of those few survivors? What was his story? Another marker tells the story a little better:

ANDREW JACKSON SOWELL

BORN IN TENNESSEE 1815

CAME TO TEXAS ABOUT 1829

SERVED IN THE ARMY OF TEXAS

A COURIER FROM THE ALAMO, HE LEFT THE

FORTRESS JUST BEFORE IT FELL TO HURRY

REINFORCEMENTS AND SUPPLIES

DIED 1848

HIS WIFE LUCINDA TURNER SOWELL

BORN 1827 - DIED 1883

ERECTED BY THE

STATE OF TEXAS 1957

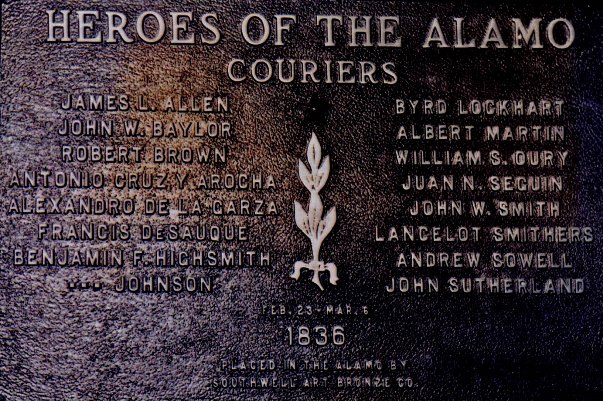

Ah ... a courier from the Alamo. Yes, there were some men who rode out of the Alamo. Albert Martin rode out with Lt. Colonel William Barret Travis's famous letter "To the People of Texas and All Americans in the World," then returned with the Gonzales relief force and died in the battle. John W. Smith rode in with the Gonzales men, then rode back out to deliver more letters from Travis. Juan N. Seguin was another Alamo messenger who, like Smith, survived. A bronze plaque in the Alamo long barracks museum commemorates sixteen men who are said to have been couriers from the Alamo: Martin, Seguin, Smith, and thirteen others, including Andrew Sowell. This plaque, like the large Alamo cenotaph monument and much of the other commemorative Alamo work done in early 20th century, was based on the research of Amelia Williams, who wrote her doctoral thesis, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of its Defenders," in 1931. Williams' thesis was edited and published in parts in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly in 1933 and 1934. In both editions, Williams presents the names of fifteen men who her investigation "seems to show pretty conclusively" that they were sent from the Alamo at some time between February 23 and March 6, 1836.1 One of them was Andrew Sowell. Williams wrote that Sowell and Byrd Lockhart "went from the Alamo 'just before the fall,' to try to hurry reinforcements and to bring in supplies for the soldiers.'"2 The wording on the 1957 grave marker shows Williams' obvious influence over Sowell's legacy.

Other authorities agree that Andrew J. Sowell was a messenger from the Alamo. Sowell's biography on the Texas State Historical Association's web site, written by Alamo historian Bill Groneman, reads:

Sowell served in the garrison of the Alamo, but shortly before the final battle he and Byrd Lockhart were ordered out to obtain supplies. They were delayed in Gonzales buying cattle and other supplies and did not return to the Alamo before its fall.

As of this writing, Sowell's Wikipedia entry reads:

In February, 1836 Sowell volunteered again during the Siege of the Alamo. Although he served in the old mission fort while the army of Santa Anna was already in the vicinity of Bexar, he and Byrd Lockhart were sent out as couriers and foragers. They went as far as Gonzales, Texas to buy cattle and supplies for the Alamo garrison. But upon their return to San Antonio, they were not able to enter as the Alamo was surrounded by Santa Anna's army.

This article will present a biography of Andrew J. Sowell followed by analysis of his purported role as an Alamo courier. The information about Sowell presented here comes principally from two sources. The first is a book called Rangers and Pioneers of Texas, published in 1884, three years after his death. The writer was Sowell's nephew, who was also named Andrew J. Sowell. It is important to note that Rangers and Pioneers of Texas is not a history, nor is it a biography of Sowell. It is a collection of stories set on the Texas frontier in which Sowell is a recurring character. Most of the stories are based on actual events, but the nephew took great liberties with historical accuracy in telling them, and some are outright fabrications. An example of one of Sowell's tall tales is the story about how the family patriarch, John Sowell, made the first Bowie knife at his blacksmith shop in Gonzales, based on a wooden prototype Jim Bowie gave him. In the story, it was also John Sowell who gave it the name, "Bowie knife." In reality, Jim Bowie's brother, Rezin, made the first Bowie knife, and it appeared in national newspaper reports five years before John Sowell was a blacksmith in Gonzales. For this reason, our biography of Andrew J. Sowell uses Rangers and Pioneers only for basic data such as names and ages of family members, dates and places of homes, and other information that is unlikely to have been distorted for storytelling purposes. In order to avoid confusion between the uncle, who is the subject of this sketch, and the nephew, who was the writer, the uncle is referred to from here below as "Andrew" or "Andrew J.," while the nephew is referred to as "A. J."3

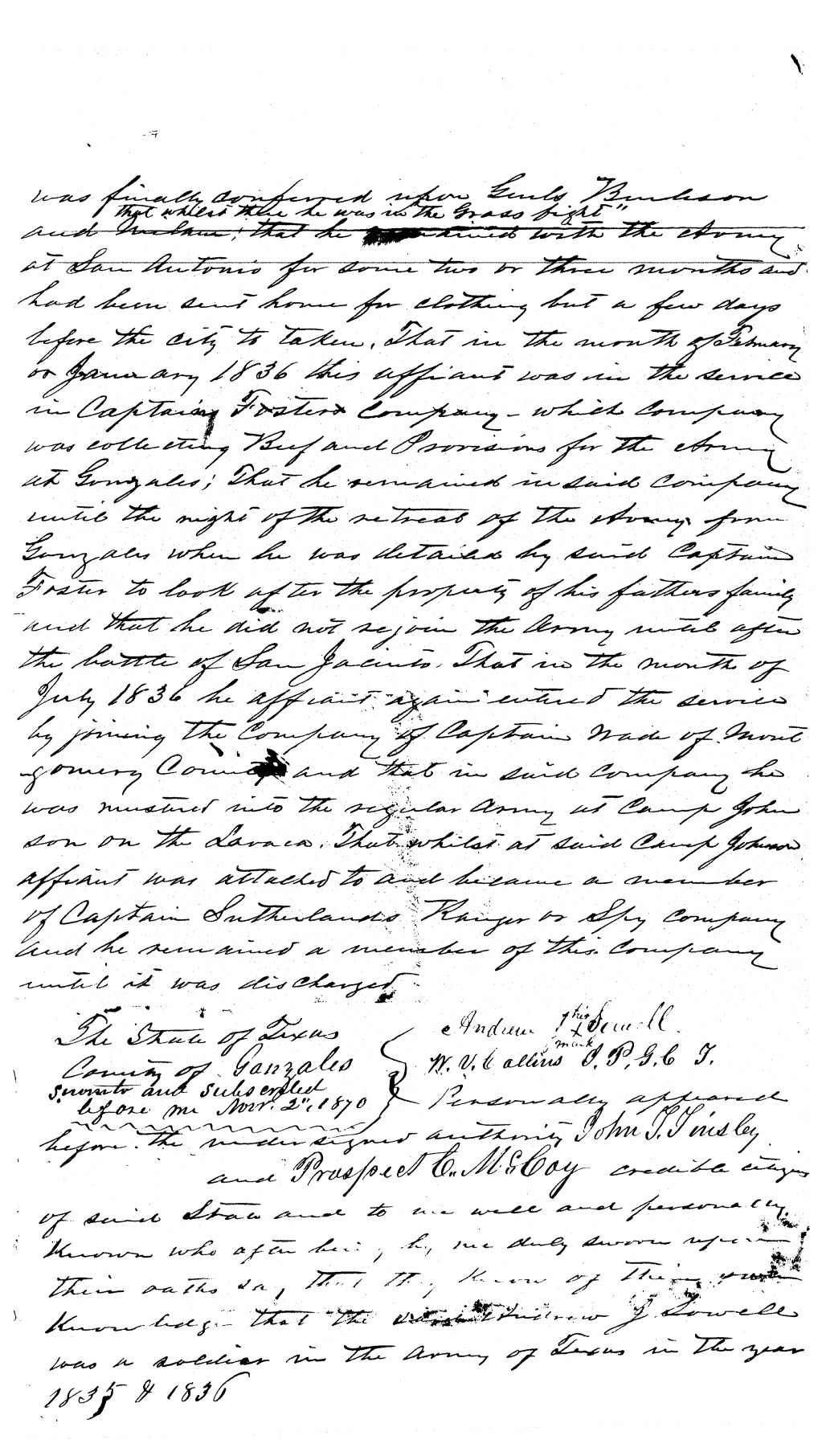

The second principal source for this biography is Andrew J. Sowell's pension claim file. In 1870, Sowell applied for a veteran's pension from the state of Texas. His application was suspended or paused in 1871 because the reviewer felt that it lacked sufficient evidence to support his claim. Sowell submitted an additional packet of materials in 1874, and then his claim was approved. The evidence in this pension claim is of very high quality. While Sowell's 1874 claim provides evidence that the 1870 claim does not, and vice versa, they are consistent with each other, and mesh very well. The claim package also contains supporting affidavits from witnesses and other documentation that corroborates his claim. Moreover, the claims Sowell made about the dates of his military service, the names of his captains, etc. match very well with known or generally accepted Texas history. In short, there are no holes in it, either internally or externally, except for a few very trivial matters, such as whether he was a private or fourth corporal in a certain captain's company. The pension claim package also contains some basic biographical information on Sowell, such as age, origin, number of children, etc. This information also appears to be accurate.

In addition to the two sources named above, our biography of Sowell uses other military records from the Republic and state of Texas, General Land Office documents and maps, U.S. Census records, and other materials commonly used in 19th-century Texas biographical research.

Biography of Andrew J. Sowell

Andrew Jackson Sowell was born in Davidson County, Tennessee on June 27, 1815. His parents were John Newton Sowell and Rachel Sarah Carpenter Sowell. He was the fifth of eight children. His siblings included older brothers Lewis and William, younger brothers John and Asa ("Asa J. L."), and sisters Rachel, Sarah, and Mary. In 1830, the Sowell clan emigrated to Texas. John received a headright grant in De Witt's Colony, on the left bank of the Guadalupe River, at the future site of the town of Seguin. He did not settle there at first, however. Instead, being a blacksmith by trade, he located in downtown Gonzales and set up a blacksmith shop.

In 1832, John Sowell moved his family to his grant. Its territory included the southeast section of the present city of Seguin's city limits and extended down the Guadalupe River for about six miles. The homestead was located on the river at the mouth of a small creek, often not depicted on modern maps, that they called Sowell's Creek.4 Before long, the family moved back to Gonzales because of Indian trouble. A. J. Sowell writes that after the Mexican government loaned the colonists a cannon to use for defense against Indians, John Sowell collected scraps of iron to use in it for ammunition.

In September 1835, relations between Texas and the centralist government of Santa Anna had become irrevocably strained. On September 27, Lieutenant Francisco de Castañeda of the Mexican army arrived from San Antonio de Bexar with a company charged with retrieving the cannon. Albert Martin and seventeen other Gonzales men stalled Castañeda while putting a call out to the surrounding farms and towns. John Sowell was one of these so-called "Old Eighteen" defenders of the cannon. Hundreds of men arrived over the next few days. They elected John H. Moore as their colonel and told the Mexicans that the only way to get their cannon back was to "come and take it." On October 2, there was a minor skirmish between the two sides in Ezekiel Williams' field. The Mexicans left without their cannon, and the Texas Revolution had officially begun. Texans now call this event the Battle of Gonzales. Andrew J. Sowell, who was there, called it the fight at the Williams place.

The militia at Gonzales soon decided that it was necessary to drive the Mexican army out of Texas. Andrew Sowell enlisted in Captain Martin's company for three months. He was one of the first four scouts who were sent to Bexar to observe the Mexicans' movements. He returned to Gonzales and marched to Cibolo Creek as part of the volunteer army under the command of Stephen F. Austin. The army then slowly made its way to Bexar. Sowell participated in the Battle of Concepcion on October 28 and the Grass Fight on November 26, both on the outskirts of Bexar. The campaign was taking longer than many men had planned for, and the weather was starting to get cold. A few days after the Grass Fight, Sowell was sent home to get some warmer clothes. It is unclear whether this was a purely personal furlough or whether he was meant to bring back a supply of coats for his company, but in any case, while he was gone, the city of Bexar was taken. The Mexican army was sent marching toward the Rio Grande. The war was over, for the moment.

On February 24, Lancelot Smithers rushed into Gonzales from Bexar, bringing the news that the Mexican army had returned and placed the Texians at Bexar under siege in the fortified Spanish mission known as the Alamo. Colonel Travis requested reinforcements immediately. Lieutenant George Kimball activated a group of men who had previously enlisted to form the Gonzales Ranging Company. The next day, February 25, Albert Martin rode into town with another urgent appeal from Travis. He and Kimball gathered a few more men and departed for the Alamo on February 27.

As Travis's appeals were circulated throughout Texas, hundreds more men came to Gonzales. As the closest town to Bexar, it was both the logical location for staging an Alamo relief effort as well as the next town to be threatened in case the Mexicans prevailed at Bexar. Andrew J. Sowell was one of the men who joined the growing militia. He enlisted in Captain Randolph Foster's company and was assigned the job of procuring beef cattle and other provisions for the army. On March 7, Lt. Colonel James C. Neill took a company of about fifty men toward Bexar to succor Travis and his men. The rest, including Sowell, remained at Gonzales. Neill's party returned a few days later, reporting that they encountered Mexican cavalry, and they believed the Alamo had fallen. After this sad news was confirmed, General Sam Houston, who had just arrived, ordered the town of Gonzales to be evacuated and burned. The army helped the colonists get out of town. Captain Foster detailed Sowell with looking after his father's household and belongings.

To escape the advancing Mexican army, some of the Sowells boarded a ship in Galveston Bay. A. J. Sowell writes that once Andrew's mother and younger siblings were safely on board, Andrew went to rejoin Houston and his men, but by the time he got to them, the Battle of San Jacinto was over, and with it, the war.

The family then settled in Brazoria County area for a time. On June 30, 1836, Sowell enlisted in the Texas army for three months in Captain John Marshall Wade's company. This company went to Camp Johnson on the Lavaca River. There, Sowell joined Captain George Sutherland's ranger or spy company and stayed with it until the expiration of his enlistment.

In 1838, some of the Sowells returned to Gonzales. By that time, Andrew's brother William and sister Sarah were dead. His brother Lewis remained in Columbia and died shortly after. His other sisters were presumably married. The people who moved back home, then, were Andrew, his parents, and his younger brothers, John and Asa. A short time after, John Sr. died. The remaining family then moved back to their property near Seguin.

From March 16 to June 16, 1839, Andrew and his brothers served in Captain Matthew Caldwell's company of Texas Rangers. They fought against a band of Mexicans and Indians led by Vicente Cordova, a Mexican-Texan who was against Texas independence and was leading a rebellion against the new republic. Caldwell's company defeated Cordova and pursued him past the Frio River.

In June 1841, Sowell enlisted in Captain James H. Callahan's company of "Minute Men." These men were not full-time soldiers, but were committed to responding in times of need. There were many of those; he was activated eight times in a five-month period. With this unit, he fought in the Battle of Plum Creek, a decisive defeat of the Comanches near present-day Lockhart.

Sowell's last military activity was apparently at the Battle of Salado Creek in March 1842.

On July 7, 1842, at age 27, Sowell married Lucinda Turner, age 15. They had nine children. The Sowell family was significant in the founding of Guadalupe County and the city of Seguin. Andrew was one of four men commissioned by the Guadalupe County court to build the Guadalupe County portion of a road from Seguin to Bastrop.

Sowell was approved for a veterans' pension from the state of Texas in 1874. There were more approved pensions than the state legislature had anticipated, however. The pension fund's appropriation was exhausted by 1876, and no more payments were made.

Andrew Jackson Sowell died in Seguin on January 4, 1883, at the age of 68. His wife, Lucinda, died before the end of the month, at age 55. They outlived four of their children. The other five died between 1922 and 1946.

In 1883, A. J. Sowell, the son of Andrew's brother, Asa J. L. Sowell, published a book, Rangers and Pioneers of Texas, which presented fictionalized accounts of various frontier and Texas Revolution figures, including his late uncle. In one of these stories, Colonel Travis sends Sowell from the Alamo to procure beef for the besieged garrison. In the early twentieth century, Alamo researcher Amelia Williams listed Andrew Sowell as an Alamo courier, based solely on A. J. Sowell's stories. He has since been accepted as an Alamo courier by most authorities, even though the service record he presented in his pension claim shows that he was in Gonzales before, during, and after the siege and battle of the Alamo.

Analysis of the Belief Sowell Was an Alamo Messenger

As the above biography of Andrew J. Sowell shows, the common yet mistaken belief that he was an Alamo messenger comes from Amelia Williams' reliance on a secondary source, which is a story his nephew told about him. Williams, as a doctoral student in the field of history, should have done more research. Sometimes, where primary documentation is lacking, family tradition becomes the historian's last resort, but there is and was no lack of primary evidence in Sowell's case. Perhaps Williams did not see Sowell's pension claim file, which paints the clearest picture, because it was not filed in the General Land Office, where she did most of her research, but she must have seen the land office document entitled Republic Donation Voucher 290, which summarizes Sowell's 1835 and 1836 army service without ever mentioning the Alamo. She also would have noticed the absence of Sowell's name on any muster rolls or other documents from the revolution. These are the same lists Williams checked hundreds of other names for. For Williams to rely on a book full of dubious and obviously false stories, to the exclusion of the available documentary evidence, and then state that her research "seems to show pretty conclusively" that Sowell was an Alamo messenger is but one of hundreds examples of how her "critical study" of the Alamo is a sham.

A. J. Sowell did not cite any evidence for his stories, but sometimes he did cite other stories. In the case of his uncle, he provided this quotation from an article written in 1881 by Bella French Swisher and published in the American Sketch Book:

Mr. A. J. Sowell is perhaps the only man living that lived to see a monument erected to his memory, by his country for his self-sacrifice, and for his country's freedom. His name is said to appear among the fallen at the Alamo. Mr. Sowell was born in Tennessee, came to Texas in 1829, and soon after his arrival, entered the Texas army; was with Bowie in the battle at the Mission, near San Antonio. He was in the Alamo, but a short time before the fort was surrounded by the Mexican forces, Mr. Sowell, and one other, was detailed and sent out after beef to supply the fort, but before they had time to procure the beef, the fort had been surrounded; and no country has ever lost a grander, and nobler, and braver set of men, than Texas lost at the fall of the Alamo.

In tandem with the above story, A. J. Sowell writes:

And, although Andrew Sowell escaped the massacre at the Alamo, by being on detached service, yet he left such a short time before the fall, his name was engraved on the monument erected to the memory of those brave and gallant few who fell.

Note that Swisher and Sowell tell the story a little differently. In Swisher's version, Sowell left the Alamo "a short time before the fort was surrounded by the Mexican forces." In A. J. Sowell's version, he left "a short time before the fall." Swisher, then, seems to have Sowell leaving on or before February 23, while A. J. Sowell has him leaving well after the siege had begun, almost before the battle, perhaps as late as March 5. Neither way makes any sense. Until the Mexican army was spotted outside Bexar at about 3:00 p.m. on February 23, Colonel Travis was not expecting the Mexicans to arrive until mid-March. There was plenty of time to prepare, and no need to go all the way to Gonzales to get beef cattle. Once the Mexican army was spotted, the Texians switched into high gear, bringing everything they would need, including cattle, into the Alamo. In Travis's famous letter of February 24, he wrote that they "got into the walls twenty or thirty head of beeves."5 In all the letters Travis wrote during the siege, he requested men above all else, and also ammunition and gunpowder, but he did not express that there was insufficient food. Susanna Dickinson stated that there was enough food inside the Alamo to last for thirty days.6 And if the men at the Alamo had needed cattle, there were plenty at the Seguin and Flores ranches south of Bexar. Going to Gonzales for cattle would have been ridiculous. Williams must have noticed how Swisher and Sowell's claim that Sowell was sent to procure beef cattle made no sense, for in "A Critical Study," she edited it to read that he was sent "to try to hurry reinforcements and to bring in supplies for the soldiers." Swisher and Sowell did not mention hurrying reinforcements or procuring "supplies"; they both mentioned beef cattle. Williams did not mention beef cattle.

An even larger problem with Swisher and Sowell's story is their claim that Andrew J. Sowell's name was included on a monument to the fallen Alamo soldiers. The monument they are both referring to was constructed in 1841. According to historian Reuben M. Potter, who participated in its construction, the list of names was provided by George Sutherland, who was a member of the Republic Congress at the time.7 It was relocated to various cities until 1858, when it was purchased by the state and permanently placed in the vestibule of the old capitol building in Austin. It was ruined in the capitol fire of 1881 and was subsequently dismantled. At least two transcriptions of the names were made and published. One was made by D. W. C Baker and published in A Texas Scrap-Book in 1875. It was reprinted in the Texas Historical Association Quarterly, April 1903 edition. The other transcription was made by former Governor Elisha M. Pease and was published in the Galveston Daily News on July 19, 1876. Andrew J. Sowell's name is not on either list. There is a "Sewall" on the Baker list. Pease reproduced this name as "Sewel, M L" in his list. The person referred to is Alamo defender Marcus L. Sewell. Swisher and A. J. Sowell may not have known that there was a Marcus L. Sewell at the Alamo and simply assumed that "Sewall" was Andrew J. Sowell. Williams, however, should not have made that assumption, for she knew about Marcus L. Sewell and included him in her list of fallen Alamo defenders.

This misinterpretation of the name on the monument seems to be where the mistaken idea that Andrew J. Sowell was an Alamo courier originated. Someone, or some people, saw the name, thought it referred to Sowell, and then assumed that meant he was at the Alamo. He obviously did not die there, however, so he must have been away at the time of the attack. Someone else then remembered that he was in Gonzales in late February and early March procuring beef cattle for the army. People took a few isolated data points and drew a jagged line between them to come up with the story: Sowell was at the Alamo, Travis sent him to procure beef cattle, he went to Gonzales, and he was there when the Alamo fell. It made sense to someone who did not know that the Alamo had plenty of beef already and did not think about the unreasonable distance and time involved in bringing cattle in from Gonzales. But, this theory was actually a chain of suppositions that began with an incorrect belief that Sowell's name was on the Alamo monument. It was not.

Williams took the story passed along by Bella Swisher and A. J. Sowell and ran with it. She realized that the "sent out after beef to supply the fort" aspect of the story did not make any sense, so she changed that part to "to hurry up reinforcements and to bring in supplies." But Williams did not stop there with her alterations of the story. She added this:

A. J. Sowell furthermore states that Andrew Sowell left the Alamo so short a time before the fall that all his friends thought that he was a victim of the massacre, and this became so generally believed that his name was placed on the first Alamo monument.

There are so many dishonest statements in Williams' "A Critical Study" that it is hard to keep track of which one is the worst, but this one probably at least makes the top ten. A. J. Sowell never wrote this. Here, again, is what Sowell wrote:

... he left such a short time before the fall, his name was engraved on the monument ...

Williams added a full twenty words of nonsense of her own and attributed it to Sowell. Why is it nonsense? Remember Andrew Sowell's biography. He was in Gonzales with his family when the Alamo fell, went on the Runaway Scrape with hundreds of other families, served in the army three months, returned to Gonzales, and served in two Texas Ranger companies, all before the Alamo monument was constructed. So, who were these "friends" who thought he was killed in the Alamo? Certainly not any of the members of his large family, the people he traveled with after the fall of the Alamo, or any of his Ranger captains or companions. Certainly not George Sutherland, who was his company commander for three months after the Revolution. Williams pretends that the list of names on the monument was compiled from "general belief," when, according to Potter, it was compiled by the same man who Sowell served under in late 1836.

Conclusion

Andrew J. Sowell was a soldier from Gonzales who fought in the Texas Revolution campaign of 1835, including the Battle of Gonzales, the Battle of Concepcion, and the Grass Fight. He went home to Gonzales after the Grass Fight and did not return to Bexar during the revolution. When Travis's messengers arrived at Gonzales to announce that the Alamo was besieged by the Mexican army, Sowell enlisted in Captain Randolph Foster's company and was tasked with procuring beef cattle for the Texian army that was rallying at Gonzales. After the Alamo fell, he went east with his family during the Runaway Scrape. He served under Captain George Sutherland in the second half of 1836. He moved back to Gonzales with his family in 1838 and then moved to his father's grant at present-day Seguin. He served in Captain Matthew Caldwell and Captain James H. Callahan's companies of Texas Rangers and fought at the Battle of Plum Creek. After his retirement from the military, he settled in Seguin, married Lucinda Taylor, and had nine children. He played a notable role in the founding of the town of Seguin and of Guadalupe County. He died in 1883. Claims made by writers and historians that he was an Alamo courier or messenger are false; he was in Gonzales before, during, and after the siege and Battle of the Alamo.

By David Carson

Page last updated: May 2, 2024

1Williams, p. 164.

2Williams, p. 308

3The reader should be aware that this is purely our convention, adopted just for this one article to avoid confusing the reader. In fact, both men were known as Andrew, Andrew J., and A. J.

4This creek entered the Guadalupe River south of present-day Seguin Auxiliary Field, just west of Farm-to-Market Road 1117.

5Hansen, doc. 1.1.4, William B. Travis, public pronouncement, 2/24/1836

6Hansen, doc. 1.2.8, Susanna Dickinson (Hanning), interview, 9/23/1876

7Hansen, doc. 1.11.2, Reuben M. Potter, letter to William Steele, 7/10/1874.

- Hansen, Todd (ed.), The Alamo Reader, 2003.

- Jenkins, John H. (ed.), Papers of the Texas Revolution.

- Pease, Elisha M., "Muster Roll of the Alamo," Galveston Daily News, July 19, 1876.

- Raines, C. W., "The Alamo Monument," Texas Historical Association Quarterly, April 1903.

- Sowell, Andrew J., Rangers and Pioneers of Texas, Shepard Bros. & Co., 1884.

- Weinert, Willie Mae, “An Authentic History of Guadalupe County,” The Seguin Enterprise, 1976.

- Williams, Amelia, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and the Personnel of its Defenders," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, April 1934.

- Republic claims file 81322, "Pension Claim Application File, Sowell, Andrew J."

- Texas Muster Roll Index Cards, 1838-1900.

- U.S. Census, 1850, Guadalupe County, Texas.

- U.S. Census, 1860, Guadalupe County, Texas.

- U.S. Census, 1870, Guadalupe County, Texas.

- U.S. Census, 1880, Guadalupe County, Texas.