Benjamin F. Highsmith

Benjamin F. Highsmith

A New Alamo Survivor in 1900

"The News Briefed," read the title of a column in the December 2, 1905 edition of the Galveston Tribune. The one-sentence stories vary from dreadful: "A mail clerk attempted to board a train at Silsbee and both legs were cut off," to mundane: "The Methodist conference at Pittsburg was engaged with routine matters," to mundanely dreadful: "A Calvert child died from the effects of eating matches." Among them was this announcement: "Benjamin F. Highsmith, the last survivor of the Alamo party, is dead."

The general public had only known about this last survivor of the Alamo for a few years. In March 1900, S. C. Malone of Weatherford sued A. O. Moran in Parker County in a dispute over the 1925-acre Malone survey near Millsap. The tract had originally been granted to the plaintiff's ancestor, William T. Malone, for his death at the Alamo on March 6, 1836. Three hundred miles away, George A. Barker, a notary public in Uvalde, was sent to Bandera County to take the depositions of an elderly man who claimed he knew the old Texian soldier when they were in San Antonio together... at the Alamo.

"My name is Benjamin F. Highsmith. My age, to my nearest birthday, September 11, 1900, is 84 years."1

This man would have been 19 on the day of the historic battle of the Alamo. That fits. He would have been one of the younger Texians in the compound, but not quite the youngest. One or two 17 year olds and a half a dozen or more 18 year olds were there.

The questions put to Highsmith were in the form of an interrogatory. Both parties' questions were written out in advance. The plaintiff's questions were asked first, in order, and then the defendant's. Highsmith could not read or write, so Barker dictated the questions to him and recorded his answers. The session took place in Highsmith's hometown of Utopia, maybe at his residence, on April 2, 1900. Only Highsmith and Barker were present. The quotations included below are taken from the transcript, with all punctuation, abbreviations, and misspellings preserved.

Highsmith swore that when the Texas Revolution started, he resided in Bastrop County. He joined John Alley's company on September 20, 1835 and stayed in it through the siege and battle of Bexar. After San Antonio was retaken, about half of the volunteers went home. He was in the half that stayed.

I remained in "The Alamo" from the fall of San Antonio to the 24thday of February, A. D. 1836. I was not present during the whole siege. On the 24th day of February, A. D. 1836, the last date above given, Travis sent me with an express to Fannin at La Bahia. I went alone.

Highsmith stated that he knew William T. Malone, the man whose land grant was the subject of the lawsuit. He first met him in San Antonio. "I think he belonged to Capt. Cary's company," he stated. The only other thing he remembered about Malone is that he remained in the Alamo when he left. If he stayed there, he was killed.

"They were all killed. There were no survivors," Highsmith said.

The plaintiffs asked Highsmith if he ever attempted to return to the Alamo. He said he did.

On the first day of March, 1836, on my return, I came in sight of the city of San Antonio. I did not go in, because I could see that the Alamo was surrounded by Mexican cavalry. I then went to Gonzales to Houston's army, and joined it.

By 1900, it was believed that the pool of potential Alamo eyewitnesses had been exhausted. Susanna Dickinson, a survivor of the battle who never had much to say about it, died in 1883. Joe the slave told his story on March 20, 1836 and was never recorded talking about it again. Juana Alsbury died in 1888. Juan Seguin died in 1890. Enrique Esparza had not been discovered yet. Madam Candelaria, who no one believed anyway, died in 1899. Louis Rose... no, let's not get into that, and it does not matter, because he was long dead. And now, after 64 years, someone just appears out of nowhere, saying he was at the Alamo. If ever a witness needed to be cross-examined, Benjamin F. Highsmith did.

The defendant's interrogatory was aimed at probing Highsmith's credibility as an Alamo witness. First, he was asked to substantiate his overall military history. On this topic, Highsmith was positively verbose. He said he enlisted in Gonzales on September 20, 1835. He named eight battles he fought in. They included eight of the ten armed engagements between Texas and Mexico which Texas won, not just during the Texas Revolution, but spanning from 1832 to 1842. He was not in any of the battles that Texas lost. That is quite an impressive military career!

Highsmith was asked to name as many members of his company as he could. He named twelve members of Captain Alley's company, which were "about all I now recollect."

Highsmith was next asked about his service at Bexar and the Alamo. He gave the same answers as in the plaintiff's interrogatory, with one exception. He repeated his assertion that he left the Alamo on February 24 to carry an express to Fannin at La Bahia, but in answer to the question, "Had the Mexican army reached San Antonio when you entered the fort, or when you left there?" he stated, "They had not reached San Antonio when I left with the express to Fannin." Alamo historians scratch their heads every time they read that part, because the Mexicans arrived at San Antonio at about 3 p.m. on February 23 and had the siege in place by 4 p.m.

Witnesses and deponents in matters such as this were often asked to give a physical description of the person they claimed they knew. There were no photographs in Texas in 1836 and hardly any painted or even drawn portraits, so the only way most people knew what someone looked like was from a verbal description. Highsmith obliged the defendant's request to describe William T. Malone. He said it "was hard to do after a lapse of so long a time," but he managed to recall that he was about five feet ten, 160 pounds, square built, about 20 to 25 years old, with dark hair and blue eyes. He remembered nothing "peculiar" about the man's appearance. By the standards of the time, that meant he did not have a wooden leg, missing fingers, an ear cut off, a back hump, etc.

The defendant's interrogatory of Highsmith shows they were skeptical about whether he really was at the Alamo. They pressed him for answers about who else was there, what did he remember about the buildings, and, last but not least, where he had been for the last 64 years. The defendant's lawyer would have made a pretty good Alamo researcher. Unfortunately, this is where Highsmith stopped being so helpful. To the question, "Can you describe the personal appearance, or give the initials of any other person who served at the Alamo? he answered:

I can.

One can imagine the notary, Barker, dipping his pen in the inkwell and cocking his head, waiting for Highsmith to continue. The two men might have stared at each other for a few seconds—the notary waiting for the names and descriptions he asked for, and which Highsmith said he could provide, and Highsmith waiting for the next question. As Barker could confirm at that moment, the stare of an elderly rural man can be intimidating. Continuing with the next question on his list, Barker asked Highsmith how many rooms were on the ground floor of the Alamo, on the second floor, and how many doors were on the south side of the compound. "I never counted the rooms," Highsmith answered. "I do not know. I do not know."

Next, Barker asked the question that was on everyone's mind:

Why is it that you have never contributed all the information which you possessi [sic] with reference to this important event to the world before now? Do you not know that the Alamo Monument Association, have for several years been making diligent effort [sic] to gather every fragment of information or facts connected with the Fall of the Alamo?; that John Henry Brown, Yoakum, Thrall, and other historians, spent years gathering information on this subject? Why have you not spoken?

It seems like, by this time, the defendant's lawyer was pressing Highsmith for answers not so much to help his client or his case, but because the public needed to know. For a new supposed Alamo eyewitness to come forward in 1900—that was the real story, one that was of much greater importance than a dispute over a tract of land. The attorney was no longer deposing Highsmith only on his client's behalf; he was deposing him on behalf of the people of Texas and all Americans in the world. Highsmith's answer:

I have told lots of people about it. I know nothing about these associations. I do not know what efforts these historians put forth to obtain information. I have spoken whenever I have been asked.

Highsmith's depositions were sent to the court in Weatherford. How much they affected the outcome of the case is unknown, but the judgment was for the plaintiff, Malone.

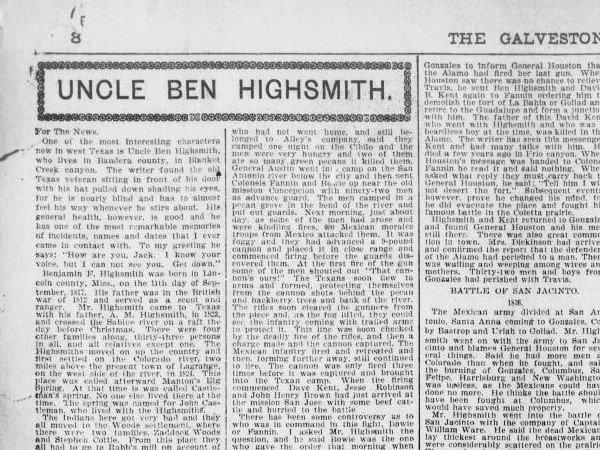

Was Benjamin F. Highsmith an Alamo Messenger?

In 1931, Amelia Williams wrote her doctoral dissertation on the Alamo and the men who were there. A slightly edited version of her Alamo study was published in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly in 1934. In it, Williams names fifteen men, including Benjamin F. Highsmith, who she finds that the evidence "seems to show pretty conclusively" went from the Alamo as messengers sometime between February 23 and March 6, 1836.2 The only evidence Williams presents for Highsmith, however, are two pieces published in the 1900s. One is a very brief synopsis of the depositions from the Malone case. Williams' other source is a biography of Highsmith written by Andrew J. Sowell and published in 1900. Sowell was a writer, not a historian, and his biography is nothing but a collection of stories Highsmith himself told. Sowell did no research and made very few observations of his own. Sowell's biography of Highsmith is, in essence, Highsmith's autobiography. Sowell first published Highsmith's story in the Galveston Daily News in 1897. Its title, "Uncle Ben Highsmith," provides a clue as to how deferential it was to the man and his claims. This article is, in all probability, the way that the Malone plaintiffs and their attorney heard about Highsmith and got the idea to depose him for their case. In 1900, Sowell republished the story in a book, Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Southwest Texas. That was Williams' source. Highsmith received additional publicity from a news story about the Malone case in the Weatherford Weekly Herald. The discovery of a new Texas Revolution veteran and Alamo survivor was the main angle of the story.

It is not as if there was no other, older, more objective evidence for Williams to look at. While there are many Alamo men for whom hard historical evidence is lacking, Highsmith is not one of them. The surviving record of Benjamin F. Highsmith's life includes:

- Stephen F. Austin's register of families

- A list of Texian soldiers who were in the army on November 24, 1835

- Highsmith's two land grant applications

- The U.S. Census of Bastrop County

- Records of his service in the Texas Rangers

- Records of his service in the U.S. Army

- His pension application with the state of Texas

There are not many Alamo men, actual or purported, who left such a substantive paper trail behind. None of it is hard for any diligent Alamo researcher to find; these are some of the same sources that are usually combed for biographical information on Alamo men. Yet, Williams not only does not cite any of it, there is no indication that she even read any of it. Despite this lack of due diligence, every known Alamo historian and researcher since Williams has accepted her conclusion that Highsmith was an Alamo messenger. Not only that, but the statements he made about other Alamo men are used in their stories. For example, Williams includes Highsmith in an already dubious story about a man who urged James Butler Bonham not to return to the Alamo; Highsmith was that man, she writes. Historian Thomas Ricks Lindley involves Highsmith as a key figure in his novel theory that a large reinforcement group entered the Alamo on March 4. The lack of published vetting of Highsmith against the usual sources, prior to the article you are now reading, is both astounding and inexplicable.

The remainder of this article will compare the autobiographical statements made by Highsmith in his depositions and via Andrew J. Sowell with the actual evidence from his life.

Claimed Date of Departure from the Alamo

Before even looking at any documents, there is one issue in Highsmith's depositions that ought to be sorted out: the day he said left the Alamo. He said, three times, that the date was February 24. That was the second day of the Alamo siege, the day that Colonel William Barret Travis wrote his famous "Victory or Death" letter. The previous day, the Mexicans took over San Antonio, raised the solid red flag of "no quarter" over the San Fernando Church, and the two sides traded cannon fire. But when Highsmith was asked, "Had the Mexican army reached San Antonio when you entered the fort, or when you left there," he answered, "They had not reached San Antonio when I left with the express to Fannin." This places his departure before 3 p.m. on the 23rd, at the latest. The discrepancy here is bigger than just the one day it may seem to be. To Alamo researchers and historians, there is all the difference in the world between someone who left Bexar before the Alamo siege began and someone who left after it was already underway. Leaving during the siege makes a man an Alamo defender or Alamo messenger. It puts him on all of the cherished rolls and lists, and gets his name engraved on a few plaques. Leaving before the siege might still make a man part of the Alamo story, but his status is reduced to a lower tier.

On the question of the date of Highsmith’s departure, Alamo researcher Todd Hansen aptly comments that these depositions demonstrate "how it can be surprisingly difficult to get a clear answer to a simple question." Hansen goes on to state that "it seems a judgment call as to what was intended."3 He resolves the discrepancy by striking the word "not" from the answer in Highsmith’s second deposition as erroneous. If that were the only possible way to solve the problem, then we might agree to do as needs must, but interpreting "They had not reached San Antonio when I left" to mean "They had reached San Antonio when I left," is a pretty serious manipulation of the evidence and should not be done lightly.

Another way to resolve the discrepancy is to change Highsmith's departure date to February 23, or some other date before then. This is also a manipulation, but it is a much less serious one. The truth is, one cannot do much historical analysis of any topic without encountering a few incorrect dates. As an example, notary George A. Barker entered April 2, 1900 as the date that he took Highsmith's depositions. The county clerk in Weatherford certified them as received on March 15, 1900. Presumably, the clerk meant to write April 15. When you do enough historical research, especially on the topic of the Alamo, you get used to altering dates you know must be incorrect. You eventually become sort of desensitized to what you are doing. With that in mind, it might be easy for most folks to say, "Highsmith meant to say February 23; he just made a mistake" and move on. Even so, let us stop for a moment to consider whether this is reasonable.

In the defendant’s interrogatory, Highsmith named eight battles he claimed to have participated in, with dates. How did he do with those dates? Not well. As a student of dates of important Texas battles, he would get a C at best. The Battle of Velasco took place on June 26, 1832; Highsmith said he was there in May. Highsmith said he fought in the Grass Fight on November 15, 1835, but that battle took place on November 26. The Battle of Salado Creek was fought on September 17, 1842, not September 11, as Highsmith said. The Battle of Arroyo Hondo took place on September 21, 1842, not September 17. Highsmith’s answers show that his memory of dates of battles long past was very imperfect.

Sowell wrote that Travis sent Highsmith with a dispatch to Fannin "on the approach of Santa Anna's army." That sounds like what Highsmith was saying in his depositions—that Highsmith left Bexar between the time that the Mexicans were spotted and their entrance into the town. If our choice is to either interpret both Highsmith and Sowell as meaning the opposite of what they stated or to alter the date given by a man who was demonstrably bad with dates, the obvious choice is to change the date.

Conclusion: Highsmith claimed that he left Bexar before the Mexican army arrived. The date was February 23.

Age

As bad as Benjamin F. Highsmith was with dates, he was even worse with keeping up with how old he was. In his deposition, he said, "My age, to my nearest birthday, September 11, 1900, is 84 years." The other sources that give a birthday for Highsmith agree that it was September 11, and there is no reason to doubt it, so the month and day are taken as fact. The year is not. Highsmith's phrasing is strange. Most people do not express their age in terms of their next birthday when that birthday is five months away. If that is what he meant, he was born in 1816. If, however, he meant he was 84 on the date of the deposition, and he mentioned September 11, 1900 for no real reason, then his birth year was 1815. Sowell gave Highsmith's date of birth as September 11, 1817, which would make him 82 on the date of the deposition, and 83 on his next birthday.

There are eight pre-Sowell pieces of documentation for Highsmith's age. None of them support any of the above birth years. The first time Highsmith stated his age in writing was in 1839, when he applied for a land grant. His application was for was a second-class grant, which entitled single men who immigrated to Texas between March 2, 1836 and October 1, 1837 to 640 acres. Highsmith actually immigrated to Texas in 1827 as a minor in his parent's household. If he had been old enough on March 2, 1836 he could have claimed a first-class headright grant of one-third of a league, or about 1,500 acres. Instead, he applied for a second-class grant, swearing that he "was seventeen years of age before the first day of October 1837."4 By that formula, he turned 17 on September 11, 1836, which means he was born in 1819. If he had been born in 1818 or earlier, he would have been 17 or older on March 2, 1836 and would have claimed a first-class grant.

Records from Highsmith's service in the U.S. army during the Mexican-American War indicate that he was 23 on September 30, 1847 (born in 1824), 23 on September 30, 1848 (born in 1825), and 25 on October 6, 1848 (born in 1823).

In the 1850 U.S. Census of Bastrop County, Benjamin Highsmith, male, teamster, from Missouri was counted twice. On September 5, he was enumerated in the household of Robert H. Grimes, as was his mother, Deborah Highsmith. He is listed as age 29 as of June 1, meaning his birth year is 1820. On September 19, he was enumerated in the household of Henry Pollard. His age listed there, as of June 1, is 30, meaning he was born in 1819. This discrepancy re-raises the question, "Why is it so difficult to get a clear answer to a simple question?" In this case, it would seem that Highsmith ignored the "as of June 1" part of the question and simply gave the census taker his age on that day, which means he was born in 1820 and turned 30 by the time the census taker saw him the second time. (He was supposed to have been enumerated only once, at his "usual place of abode.")

In 1874, Highsmith was evidently considering filing a claim for a veteran's pension from the state of Texas. He obtained a statement from two witnesses who swore on December 4 that they knew "he is now aged about fifty four years,"5 meaning he was born in 1820. Yes, this was a second-hand statement, and they said "about," but this was not two men giving their best approximation; they were affirming a statement Highsmith and his lawyer composed and gave them to sign. If Highsmith was 57 or 58 on that date, he could have told his lawyer to write that age on the statement, and his witnesses surely would have sworn to it.

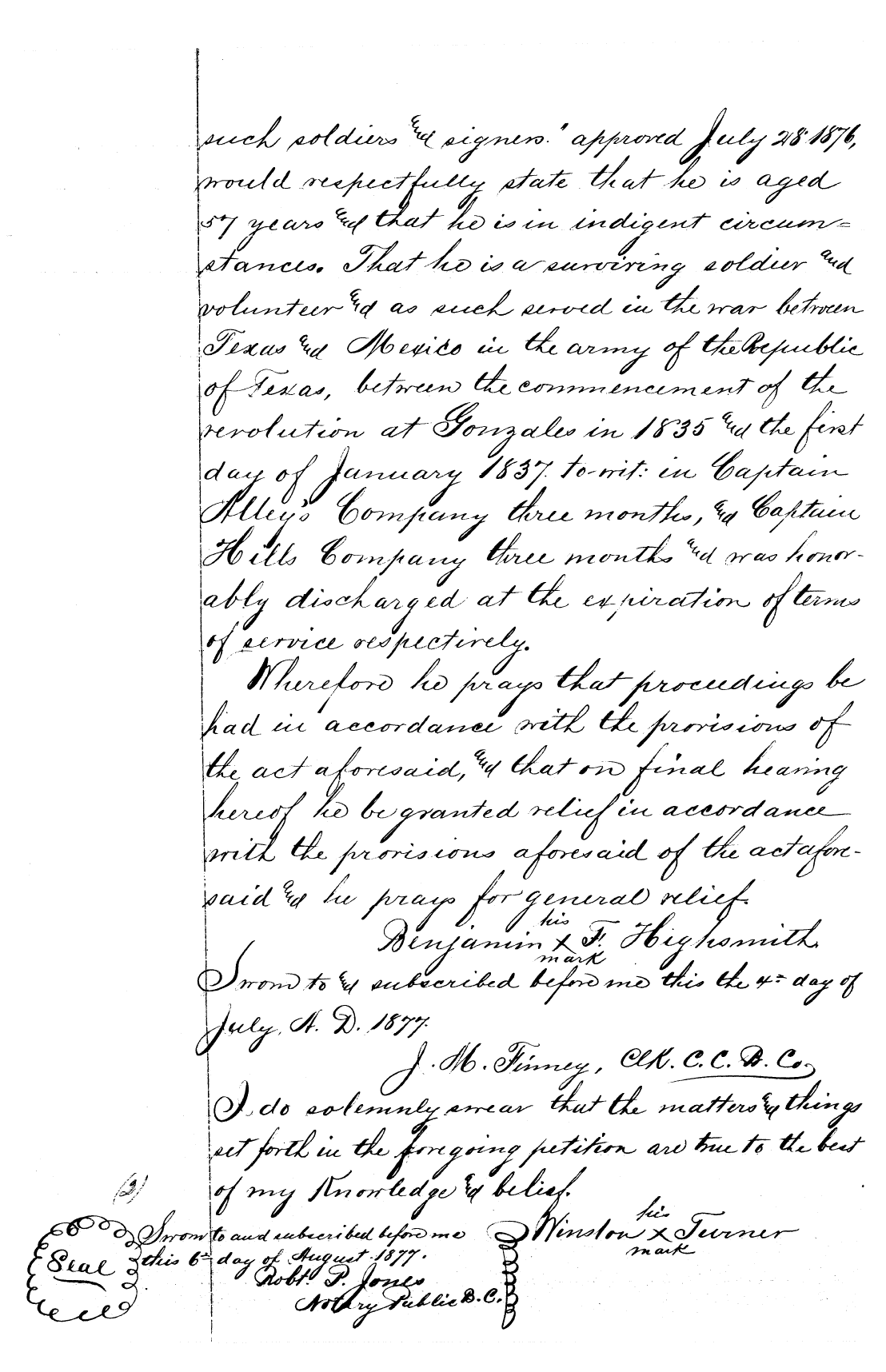

In 1877, Highsmith filed his first pension claim. His sworn statement on his application, dated July 4, was that "he is aged 57 years,"6 meaning he was born in 1819. Highsmith attached the affidavit he obtained from his witnesses in 1874 to this application.

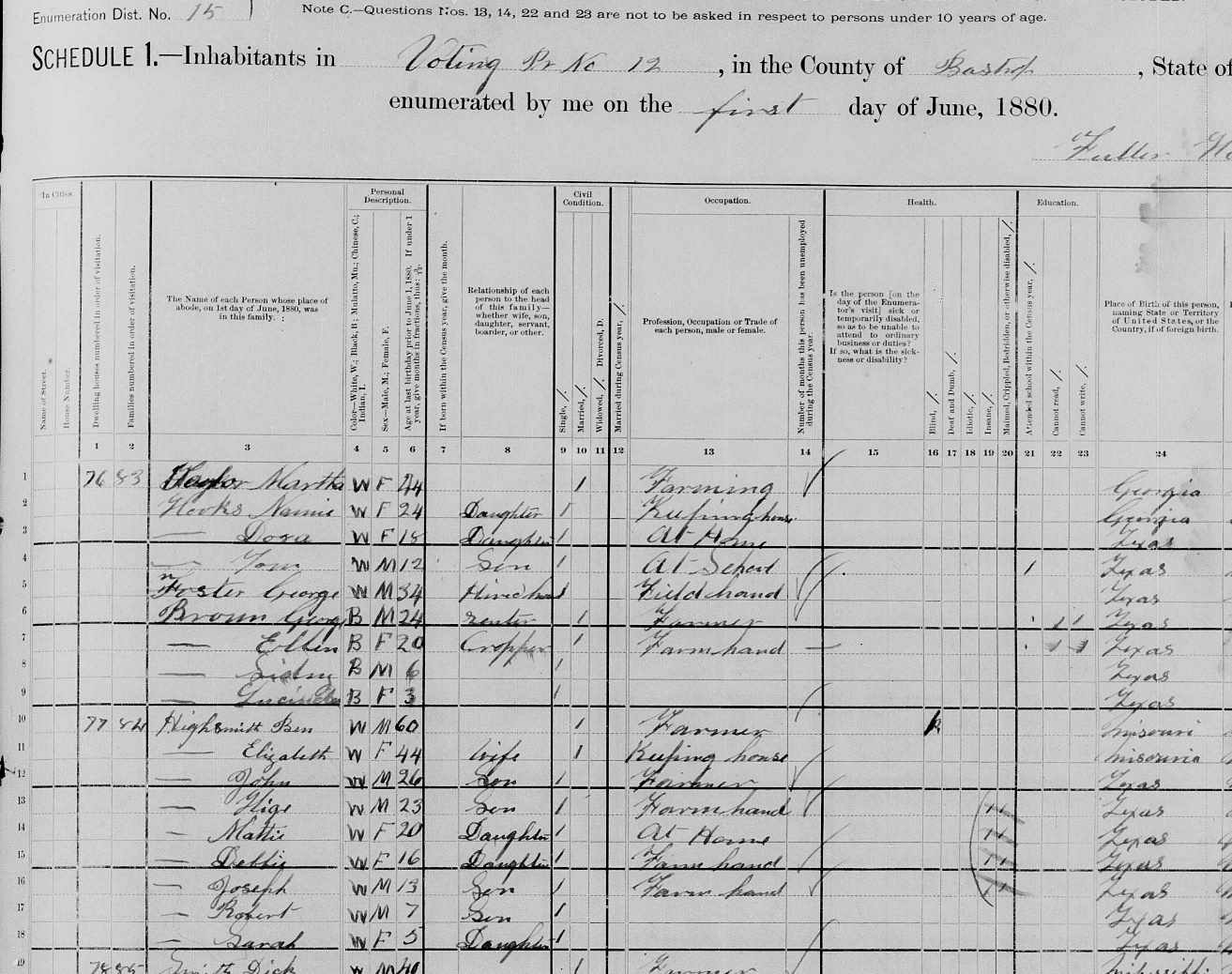

In the 1880 U.S. Census of Bastrop County, Ben Highsmith, farmer from Missouri, is enumerated as the 60-year-old head of household that included his wife, Elizabeth, 44; son, John, 26; son, Kige (Malchijah), 23; daughter, Mattie, 20; daughter, Debbie, 16; son, Joseph, 13; son, Robert, 7; and daughter, Sarah, 5. The date of this enumeration was June 1, so his age of 60 means he was born in 1819. The age of the oldest child suggests that Ben and Elizabeth were married in or before 1854. (According to a genealogy site, they were married on September 12, 1853.)

Highsmith’s date of birth is relevant to his credibility because of how it affects his age when he supposedly began taking up arms to fight for Texas. He made it seem, in his depositions, like he was either 19 or 20 at the outbreak of the Texas Revolution and when Travis selected him to carry a message to Fannin. According to Sowell, he was 18. But the documents he and his witnesses swore to in 1839, 1874, and 1877 indicate he was 15 or 16, as does the U.S. Census. It is not impossible to conceive of a 15 or 16 year old fighting for his country, but it might be hard for some people to believe that Colonel Travis, who was responsible for the lives of hundreds of men, chose someone that young to ride for ninety miles by himself to deliver an important message that could change the course of a war. Highsmith must have thought so, which is why he made himself out to be 18 when talking to Sowell and 19 when giving his depositions.

The table below summarizes Highsmith's reported ages.

| Source | Birth Year | Age at the Alamo |

|---|---|---|

| 1839 headright grant application | 1819 | 16 |

| 1847-1848 Mexican War service records | 1823-1825 | 10 to 12 |

| 1850 U.S. Census of Bastrop County | 1820 (or 1819?) | 15 (or 16?) |

| 1874-1877 pension application | 1819-1820 | 15 to 16 |

| 1880 U.S. Census of Bastrop county | 1819 | 16 |

| 1897 Sowell article | 1817 | 18 |

| 1900 Malone depositions | 1816 (or 1815?) | 19 (or 20?) |

An objective look at the documents requires us to favor Highsmith's headright grant application, his pension application, and the U.S. Census. The birth year of 1820 is the only one that witnesses other than Highsmith swore to. The birth year of 1819 is the only one Highsmith used three times, and it is also the one found in the earliest source. The Mexican War records are unsworn and are an outlier. All they prove is that when Highsmith tells you how old he is, do not believe him. The birth years of 1817 and earlier came about late in Highsmith's life, at a time when he had recently begun claiming he was not only at the Alamo, but was entrusted with an important mission by the commander. They cannot be believed when compared against older, better records.

Conclusion: The documentation indicates Highsmith was born on September 11 in either 1819 or 1820. If narrowing it down to one choice, it would be 1819. He was no older than 16 during the siege and battle of the Alamo.

Origin and Pre-Revolution History

That Highsmith was born in Lincoln County, Missouri and his parents were Ahijah M. and Deobra Highsmith are undisputed.7 Highsmith stated in his 1900 depositions, "A. M. Highsmith was my father."8 The date of the family's arrival in Texas is a matter of some confusion. Sowell wrote that Highsmith's family and four other families all came over together, 33 persons, all related except one. Sowell wrote that Benjamin crossed the Sabine River on a raft "the day before Christmas" of 1823. That is probably wrong. Ahijah Highsmith registered in Austin’s colony on April 1, 1827. On January 1, 1829, the day that he took the oath to become a settler, he stated that he immigrated to Texas in January 1828. The simplest explanation for this discontinuity is that Ahijah or the person making the record made a mistake, and January 1827 should have been written. A Bastrop County record from 1838 shows that Samuel Highsmith, whose name is listed two lines above Ahijah's in Austin’s Register of Families, immigrated in 1827. Perhaps the families crossed the Sabine River on December 24, 1826, but did not consider themselves as having immigrated to Texas until they reached a stopping point.

Samuel Highsmith's name occurs in parallel with Benjamin's throughout his life. When Samuel and Ahijah arrived at Austin's colony, Samuel was married, with no children. If he was a newlywed, he may have been about ten years older than Benjamin. Samuel was probably Benjamin's uncle or cousin.

When Ahijah Highsmith registered at Austin's colony, he applied for a league of land on the east side of the Colorado River, fifteen miles below the San Antonio Road. At that time, he was married and had five children. When he took the oath to become a colonist, he declared himself to be 34 years old and a farmer. His wife, Deobra, was 35. They had three sons and three daughters: "8 total souls." Ahijah was issued a grant to the tract he requested in his application. Texas General Land Office maps show it as situated about halfway between Bastrop and Smithville. He signed the deed on March 7, 1831. It was patented, or finalized, on April 5.

Sowell included information about several places on the Colorado River where the Highsmiths lived. He stated that they moved around several times because the Indians "got very bad."9 Sowell also wrote that the family lived in Matagorda for a while. While the Highsmith family is most strongly associated with Bastrop, Sowell may have been correct about at least some of them living in Matagorda; Samuel Highsmith's will was probated in Matagorda County.

Sowell wrote that Benjamin Highsmith went on a trading trip to San Antonio with James Bowie, William B. Travis, Ben McCulloch, Winslow Turner,10 Sam Highsmith, and George Kimble in 1830, arriving there on April 1. That is impossible; it would be a year before Travis would first be seen anywhere in Texas. Sowell than gives an inaccurate recap of the centralist-versus-federalist conflict in Mexico to explain why Highsmith ran away from home at age 15 to fight in the battle of Velasco in 1832. According to the birthdate Sowell gives for Highsmith, he was 14 at that time, not 15, and in reality, he was 11 or 12. Highsmith gives the names of some of the men he fought with at Velasco, and the names of some who died. To the extent that any of it is correct, he presumably heard about it from someone else, possibly Ahijah or Samuel. Highsmith also claimed in the Malone depositions that he fought at Velasco.

In Highsmith's self-told origin story, he is much more than just a young man who was in Texas in the early 1830's, when it all began; he was one of its first colonists, he hung around with its greatest heroes, and he fought in its first battle. Even overlooking his exaggeration of his age, his stories do not hold up to scrutiny. That is true of the stories he told about other periods in his life, including the Alamo.

Conclusion: Benjamin F. Highsmith came to Texas in December 1826 or January 1827 as a boy of seven. He grew up in his parents' house, principally in Bastrop, with possibly some time spent in Matagorda.

The Fall 1835 Campaign

In Sowell's article, Highsmith stated that he was with his father in Bastrop when they received notice from Gonzales that the Mexicans were coming for the town's cannon. This is the last time his father or any other member of his family is mentioned. He arrived at Gonzales and joined Captain John Alley's company, which was under the command of Colonel John D. Moore (better known as John H. Moore, or John Henry Moore). In the Malone interrogatories, Highsmith stated that he joined Alley’s company on September 20 and then went to Gonzales. In both versions of the story, he remained in Alley's company through the battles of Gonzales, Concepcion, the Grass Fight, and the storming of Bexar. At Gonzales, Highsmith was the person who discovered that it was possible to see the enemies' legs clearly through the dense fog by stooping down to the ground, where the visibility was clear, and he alerted Colonel James C. Neill, who was manning the cannon, to that fact. At Concepcion, he was standing behind the same tree as Richard Andrews, the first Texian killed in the Texas Revolution, and warned him to stay in cover only seconds before he was fatally wounded.

There are a lot of reasons not to believe anything Highsmith said about his serving in the fall campaign. First, he would have been eligible for a bounty grant of 960 acres for three months’ service and a donation grant of 640 acres for serving in the battle of Bexar. He never applied for either of these grants, even though he did apply for a headright grant of 640 acres in 1839. He did not claim to be a veteran of the Texas Revolution until 1877, when he applied for a pension offered to veterans of that war. At that time, he submitted a sworn statement that he served in the army for two separate three-month enlistments between October 1835 and January 1, 1837: three month’s in Captain Alley’s company and three months in Captain Hill’s or Hills’ company. Along with his application, he submitted an affidavit prepared in 1874 from two witnesses who stated they served with him in the Texas Revolution between January 15, 1832 and October 15, 1836. The starting date of January 15, 1832 is weird. The battle of Velasco, a prelude to the Revolution, occurred in June 1832. There was no conflict in January 1832, and notwithstanding the hostilities at Velasco, Texas was not in an ongoing military struggle with Mexico until October 1835.

In 1881, Highsmith submitted another pension application, which included an affidavit from two witnesses who swore that he was in Captain Alley’s company from about October 1, 1835 until about January 1, 1836, when he was mustered out and honorably discharged. Two more witnesses swore that Highsmith entered the service on or about October 1, 1835, was honorably discharged on or about December 31, 1835, and that he served in Captain John Alley's company.

If we excuse the affidavit with the weird dates, Highsmith has sworn, and been corroborated by four witnesses, that he served in the fall 1835 campaign from about October 1 through January 1 in Captain Alley’s company, then was honorably discharged. In Sowell and Malone, he elaborated on this to say that he fought in the battles of Gonzales, Concepcion, the Grass Fight, and Bexar. There were some men who had this service record, but the problem is, Captain John Alley was not one of them. A letter to Alley from Stephen F. Austin shows that he was not at Gonzales on October 2. He did subsequently march through there on his way to Victoria, then he proceeded to Goliad. He then received orders to join the main army. He was with the main body of volunteers from October 23 until the conclusion of the battle of Bexar.11 His company did participate in the Grass Fight and the battle of Bexar, but there is no indication that it was at the battle of Concepcion, which was fought by only about seventy Texians. Highsmith could not have joined John Alley’s company at Gonzales on October 1 and fought with him the next day over the cannon and later at Mission Concepcion. According to Highsmith, though, he was not only at both places, but he gave Neill important intel and tried his best to prevent Andrews' death.

At this point, it would be easy to dismiss Highsmith's claims to have served in the fall campaign as entirely fabricated, except for one piece of evidence: a document known as "List of men who have this day volunteered to remain before Bexar," dated November 14, 1835, includes the name Highsmith. That man's captain, however, is not John Alley, but "Capt Coleman." That suddenly makes sense. Robert M. Coleman of Bastrop raised a company of volunteers on September 20, went to Gonzales, participated in the battle of Gonzales, and remained with Austin’s army. His company did participate in both the battle of Concepcion and the Grass Fight. Everything Highsmith claimed about his service in the fall campaign lines up with known events if we change the name of his captain from John Alley to Robert Coleman except for one detail: during the 6-day battle of Bexar, Coleman was with the cavalry, patrolling the vicinity of Bexar.12 He did not enter the city. Alley did. Logic suggests that some or all of Coleman’s infantrymen transferred to other infantry companies, such as Alley's.

The next question would be, if Benjamin Highsmith was in Coleman's company for about two and a half months, then in Alley’s for a week at most, why would he claim that he served three months in Captain Alley’s company? Why would he, from 1877 and for the rest of his life, mention Captain Alley’s name every time he spoke about his service in the Texas Revolution, and never mention Coleman? The most likely answer is because he did not serve under either. The Highsmith who is named in Captain Coleman’s company on the "List of men" was probably one of his relatives, such as Ahijah or Samuel. Benjamin knew that his relative fought in the fall campaign and served under Captain Alley at the battle of Bexar and incorrectly believed he was in Alley’s company for the whole three months. When he decided, in 1877, to start claiming he was a veteran of the Texas Revolution, he incorporated his incorrect understanding of his relative's story into his own.

Benjamin Highsmith definitely gave incorrect information about his participation in the fall campaign in both the Malone depositions and to Andrew J. Sowell. Either he made a mistake in giving the name of John Alley instead of Robert Coleman as his captain, or he lied about being there. The fact that there is not any evidence that he even claimed participation in the fall campaign before 1877—32 years after his father's death and 5 years after his mother's—makes the lie the most logical answer.

Conclusion: Benjamin F. Highsmith, who had just turned 16 when the Texas Revolution began, did not participate in the campaign of the fall of 1835. One of his relatives was in Captain Robert M. Coleman's company for most of the campaign and transferred to Captain John Alley's company for the battle of Bexar in December.

Description of William T. Malone

William T. Malone has been accepted as a fallen Alamo defender by every Alamo historian of the 20th and 21st centuries, but there was initially some doubt because he was omitted from the casualty list that the Texas adjutant general used to confirm fallen Alamo defenders. The defendants in Malone v. Moran asked Highsmith to give a physical description of William T. Malone as a way to test whether he really knew him. If his description was off, that would suggest that either Malone was not at the Alamo, and, therefore, that the land grant was invalid, or Highsmith was not there, and therefore, he was unqualified to say whether Malone was. Their question to him, and his answer, are as follows:

Q. If you have said that you knew a Malone serving at the siege of the Alamo, then please describe minutely his personal appearance. What was there about him that would cause you to remember him so distinctly? How did you happen to become so well acquainted with this Malone, or know him so well that you are now able to give his initials and describe his personal appearance?

A. That is hard to do after a lapse of so long a time. As well as I can recollect, he was a man about 5 feet 10 in. high, square-built, weighed about 160 lbs., dark eyes and dark hair. He looked to be somewhere between 20 and 25 years of age. I was with him every day, while I was there. There was nothing that I remember peculiar about his personal appearance.

All sources on William T. Malone describe him as a young man who ran away from home in the fall of 1835 at age 18. The story goes that his father was strict, and after a particularly wild night in which he got the little finger of his right hand bitten off in a fight, Malone was afraid to return home, and fled to Texas. In 1911, writer G. A. McCall published an article about Malone in the Texas Historical Quarterly. McCall used the depositions in Malone v. Moran as his source. These depositions included Highsmith’s plus those of Mrs. Frank Malone of Memphis, Tennessee and Professor F. P. Madden of Waco. McCall writes:

Highsmith says that when he left San Antonio there was in the Alamo a young man by the name of Bill Malone, and his description of the young man's person and estimate of his age correspond with the description given by the family. They both speak of the young man's having lost the little finger on his left hand.

Highsmith did not state that there was a "young man by the name of Bill Malone." He said there was a William T. Malone who was 20 to 25 years old. Certainly, there are 18 year olds who might appear to be in their early twenties to someone in his or her forties, but Highsmith claimed he was 19 at that time. People, especially in their youth, have a keener eye for which people are in their peer age group, which are older, and which are younger, compared to when they are trying to estimate the age of someone outside of their cohort. A 19 year old describing an 18 year old as 20 to 25 counts as a mismatch, not a match. Furthermore, Highsmith said nothing about Malone missing a finger. On the contrary, he remembered nothing "peculiar" about his appearance. McCall's synopsis of Highsmith's description of Malone makes three assertions, two of which are inaccurate, which means his third assertion, which is that it corresponded with Mrs. Malone's description, cannot be given any weight.

Let it be stipulated that it would be easy for anyone to incorrectly describe a person he had not seen for 64 years in any number of ways. That being said, if Highsmith had given an accurate description of Malone, that would have helped to substantiate his own presence at the Alamo. Instead, Highsmith's credibility is not helped by his physical description of William T. Malone.

Conclusion: Highsmith gave an inaccurate physical description of William T. Malone.

The Alamo

Highsmith went for 41 years without telling anyone that he fought in the Texas Revolution. After another 20 years passed, he dropped the biggest bombshell of all: he was at the Alamo. Sowell writes:

At the surrender of General Cos a great many of the men went home. Colonel Fannin had went to La Bahia, or Goliad, before the taking of San Antonio and was in command there. Colonel James Neill was placed in command of the Alamo until relieved by Colonel William B. Travis. Mr. Highsmith stayed in the Alamo with Travis, who, on the approach of Santa Anna's army, sent him with a dispatch to Colonel Fannin, ordering him to blow up the fort of La Bahia and come to him with the men. Highsmith was gone five days, and on his return Santa Anna’s advance of 600 cavalry was on the east side of the river, riding around reconnoitering the Alamo and watching for reinforcements and messengers. Mr. Highsmith sat on his horse on Powder House hill and took in the situation...

The daring messenger saw there was no chance to communicate with his gallant commander, and slowly rode north toward the San Antonio and Gonzales road. The Mexicans saw him and large squads of them rode parallel with and closely watched him and finally came toward him at a sweeping gallop. Highsmith took a last look toward the doomed fort and trapped heroes within, and putting spurs to his horse dashed off toward the east, the last man alive to-day who talked with Bowie and Travis at the Alamo.

Sowell further writes that the Mexican cavalry chased Highsmith for six miles and gave up. He then paused to let his horse rest and heard "boom after boom of cannon." Here, Sowell inserts the arrival of the Gonzales relief force, in which he includes David Crockett and "a few men who came with him to Texas." When Highsmith arrived at Gonzales, "he found General Houston there with several hundred men on their way to succor Travis, and his report was the last reliable news he got before the fall."

Scouts were sent back to within a few miles of San Antonio to listen for the signal gun which Travis said he would fire at sun up each morning as long as he held the fort. On Monday morning, March 7, 1836, the scouts listened in vain for the welcome signal.

Alamo buffs will be able to spot dozens of errors with Sowell’s story, especially with the timeline, in which he compresses the thirteen-day siege down to about six days. For example, Houston did not arrive at Gonzales until March 11, and was immediately informed about the Alamo's fall upon his arrival, via two Tejanos that arrived earlier that day. The last "reliable news he got before the fall" was at Washington-on-the-Brazos. The scouts sent to listen for the signal gun returned on March 11. Crockett arrived at Bexar with men he met in Nacogdoches—they did not come to Texas with him—two weeks before Highsmith supposedly left. The only thing Sowell got right about the timeline is that March 7, 1836 was a Monday.

Another giveaway that Sowell's story is false is that Travis could not have ordered Fannin to "blow up the fort of La Bahia." When the siege of the Alamo was going up on February 23, Travis did send a letter, which James Bowie co-signed, requesting Fannin's assistance, but the letter said nothing about blowing up La Bahia. Nor did Travis ever mention blowing up La Bahia in any of his letters that have been preserved. Travis knew that Fannin outranked him, and he could not order him to do anything, much less destroy his own position. Sowell's reference to blowing up La Bahia shows that he was confusing Travis and Bowie's appeal to Fannin for aid with General Sam Houston's subsequent order for Fannin to blow up La Bahia, which was issued 17 days after Highsmith supposedly left the Alamo.

Nowhere in Sowell’s article does he have Highsmith leaving the Alamo after the siege was already in place. Highsmith said, in his deposition, "They had not reached San Antonio when I left with the express to Fannin." But because he said he left on February 24, and despite the fact that he was, objectively speaking, bad with dates, many have decided that he did what he said he did not do, which is leave the Alamo during the siege.

Not only did Highsmith not leave the Alamo during the siege, he did not leave before the siege, either. He simply was not there. Whoever the Highsmith was that was in the army in November went home with most of the other colonists. The large majority of men who remained in Bexar after Cos's surrender were new arrivals from the United States who did not have homes in Texas to return to, or colonists from distant settlements in east Texas. The men from Gonzales, Bastrop, San Felipe, and other "nearby" towns went back to their homes to earn their livings as farmers, blacksmiths, tanners, and storekeepers. Colonel Neill made a muster roll of the men who fought in the battle of Bexar and remained in his company; there is no Highsmith on it. There is no Highsmith on any other Bexar muster roll. His name is not on the voting list taken in Bexar on February 1 or any other surviving scrap of paper where Alamo men's names are found. He was never mentioned by any of the other men who left Bexar before the siege, or by any Alamo witness, actual or purported, except himself. He was not there, and he did not even start to claim he was there until 1895, after every person who might be able to contradict his claim was dead. Even as late 1881, when he was claiming he fought in the fall 1835 campaign, he and his witnesses swore that he was discharged on January 1, 1836, and they do not mention any other army service until San Jacinto, or later.

Conclusion: Highsmith did not go to Bexar in 1836 and was not involved in the Alamo siege or battle in any way.

After the Alamo

March 1836

In the Malone depositions, Highsmith stated that when he saw that the Alamo was surrounded, he "went to Gonzales to Houston's army, and joined it." Sowell wrote that when Houston was informed that the signal gun from the Alamo was silent, he sent Highsmith and David Kent to Fannin to order him to demolish the fort of La Bahia, retreat to the Guadalupe River, and rendezvous with him. This David Kent "was a beardless boy at the time," and his father was killed at the Alamo. "This writer has seen this messenger Kent and has had many talks with him," Sowell wrote. Out of all of Sowell's long biography of Benjamin F. Highsmith, his discussion of David Kent is notable for being the only part that Sowell personally vouched for. Sowell did not specifically vouch for Highsmith's claim that he went with Kent, however. Instead, he repeated what Highsmith told him—that he and Kent went together to see Fannin, that Highsmith told Fannin he needed his answer so he could inform Houston, and that Fannin replied, "Tell him I will not desert the fort."

Much, but not all, of what Sowell stated here does check out. The scouts came back on March 11 to report that they had not heard the signal gun. Houston did write a letter to Fannin on that date, and he did tell him to "blow up" the La Bahia fort, or "Fort Defiance," as the Texians called it, and fall back to Victoria.13 Fannin had the letter on March 14. Pre-Sowell history does not record who carried it from Houston to Fannin, but there is some evidence that it could have been David B. Kent, the 18-year-old son of Alamo defender Andrew Kent.14 In 1881, Kent submitted a land grant application in which he swore that he was an express rider from San Antonio and Gonzales in 1836. A witness swore that Kent was "a bearer of dispatches and carried many on said duty until the Texas forces retired from Gonzales."15 Kent must have told Sowell that he carried Houston's message to Fannin. There is no reason to disbelieve it. There was a large contingent of Bastrop men in Gonzales at that time, so Highsmith probably was there with his family. As for whether Highsmith went with Kent to La Bahia to tag along... sure, why not. There is one part of Sowell's story that is untrue, however, and that is Fannin's answer to Highsmith that he was refusing to follow Houston's order. Though there had been some friction between Houston and Fannin before, when the command structure of the Texas army was broken, that was no longer the case now: Houston was the commander in chief, period. Houston's orders to Fannin were unambiguous, and to make such an overt statement of insubordination was not Fannin's style. Furthermore, documentation shows that Fannin was, on March 14, arranging to procure horses, mules, oxen, and carts "in compliance with General Houston's orders."16 Sadly, he complied with those orders in the indecisive, incompetent fashion he became famous for, and waited too long to get underway, resulting in his death and the death of most of his men at the hands of the advancing enemy army. If Highsmith told Sowell that Fannin told him, "Tell him I will not desert the fort," then Highsmith lied. It is a shame, too, because otherwise, his claim that he went with Kent to Goliad to deliver Houston's message is believable. Even when we want to believe him, we can't.

Two witnesses swore in 1874 that Highsmith was part of the "Runaway Scrape"—the mass, panicked eastward scramble of American-Texans that began at Gonzales on March 13, 1836. Highsmith presumably either traveled with his family from the beginning or caught up with them after returning from Goliad.

San Jacinto

In the Malone depositions, Highsmith stated that he fought at the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. This is one of the dates he stated correctly. In the Sowell article, he said he was in William Ware’s company. Muster Rolls 44 and 45 in the General Land Office provide the names of 51 men in Captain William Ware’s company, and there is no Highsmith among them. The description Highsmith gives of that battle were probably given to him by his father, who was a private in Captain Jesse Billingsley’s Mina (Bastrop) Volunteers at San Jacinto. Benjamin Highsmith did not start to claim that he fought at San Jacinto until 1881, and there is no prior evidence to support his claim.

Fall of 1836

In 1877, Highsmith swore that he was in the Texas army for two three-month periods between October 1835 and January 1, 1837. The second of those two periods was for three months in "Captain Hills," (Hill's or Hills') company. This sounds like William Warner Hill, who led a company of rangers from July 1 to October 1, 1836. Highsmith's name is not one of the fifty names on Captain Hill’s muster roll, nor is there any obvious association between Hill and his company with Bastrop. If there was another Captain Hill or Hills who was active in the fall of 1836, his identity eludes this researcher.

In 1881, Highsmith described his fall 1836 service differently. He stated that he joined Captain William Patton’s company and served in it until about November 1, when he mustered out with an honorable discharge. He also mentioned his prior claimed service with Captain Alley. Two witnesses signed a statement swearing that they knew Highsmith served in "Cap. John Ally’s company and Col Ewd Burleson Regiment." William H. Patton was a captain at San Jacinto. Edward Burleson was the colonel of the First Regiment of infantry at San Jacinto. Burleson was still a colonel with the rangers in the fall of 1836, but the use of the word "regiment" sounds like a reference to San Jacinto. In short, the dates Highsmith and his witnesses cite are for post-San Jacinto service, but the commanders they mention pertain to San Jacinto. It is impossible to discern what Highsmith was actually claiming here. Sowell's biography of Highsmith is no help, for it does not make any mention of army service after San Jacinto until 1838. Highsmith cannot be given credit for any service in the fall of 1836 when his own claims about what he did are such a mess.

Army Service After 1836

In the Malone depositions, Highsmith claimed he fought in two battles subsequent to San Jacinto: the battle of Salado Creek and the battle of the Arroyo Hondo, both in September 1842. This is only a fraction of the frontier service he claimed to have performed in Sowell's article. Sowell places him at practically every well-known engagement against Mexicans or Indians in the history of the Republic, including the Battle of Plum Creek, the Somerville Expedition, and numerous small, unnamed conflicts. This is the one phase of Highsmith's claimed service record for which there is substantial historical support. In August 1851, Colonel Edward Burleson, Captain Jesse Billingsley, and Captain T. M. Childress certified that Benjamin Highsmith served as a private for six weeks during the Vasquez invasion of San Antonio, which occurred in March 1842, and for three weeks during the Woll invasion of September 1842. Billingsley was the leader of a company of Texas Rangers from Bastrop and was the same captain Highsmith’s father served under at San Jacinto. Benjamin Highsmith's name is found on the two muster rolls from 1842, and he was paid $47.25—$31.50 for first six weeks, and $15.75 for the last three weeks.

In Sowell's article, Highsmith claimed that he served during the Mexican-American war under famed ranger commanders Jack Hays, Sam Walker, "Ad" (Robert Addison) Gillespie, Ben McCulloch, and others. He mentions fighting in Palo Alto on May 8, 1846, Monterrey, where Captain Gillespie was killed, and Buena Vista on February 23, 1847.

U.S. Army records paint a different picture. They show that Highsmith was mustered into the service for twelve months in San Antonio on September 30, 1847 as a private in Captain J. S. Sutton's17 company and mustered out on October 6, 1848. By that time, the front-line fighting was taking place in the heart of Mexico. Highsmith's lack of elaboration on his activities during the period he is documented as having served suggests that it was unglamorous.

There were at least six Highsmiths other than Benjamin in the Mexican-American war, including Samuel, who was a captain in Hays' regiment, and William, who was a private in Captain Henry McCulloch's company. It appears that when discussing his Mexican-American War service, Benjamin F. Highsmith did the same thing he did with Velasco, the fall campaign of 1835, and San Jacinto: make himself the protagonist of war stories he heard from his relatives.

Army Service Summary – Claimed and Documented

The following table summarizes Benjamin F. Highsmith's army service, both claimed and documented:

| Source of Claim or Document | Service Record |

|---|---|

| 1839 headright application | No service mentioned in headright application, no bounty or donation application made. |

| 1851 muster rolls and service payment voucher | Six weeks for Vasquez invasion (1842) and three weeks for Woll invasion (1842). |

| 1877 Texas pension application | Served between January 15, 1832 and October 15, 1836 (witness affidavit). Served between commencement of the revolution in Gonzales to January 1, 1837, three months in Captain Alley's company and three months in Captain Hills [sic] company (sworn statement). |

| 1881 land grant application | In Captain Alley's company from about October 1, 1835 to January 1, 1836, in Captain Patton's company from about August 1, 1836 to November 1, 1836 (witness affidavit). From on or about October 1, 1835 to December 31, 1835, in Alley's company and Burleson's regiment (sworn statement corroborated by witnesses). |

| 1887 U.S. pension application | From September 30, 1847 to October 6, 1848 in Captain Sutton's company. |

| 1895 affidavit re: R. W. Ballentine | Was at the Alamo two weeks before its fall, was sent by Travis to Fannin with a message. |

| 1897 Sowell interview & article | Eighteen battles from Velasco (1832) to Buena Vista (1847), was a messenger from the Alamo. |

| 1900 Malone depositions | From September 20, 1835 until May 1845, was a messenger from the Alamo. |

The table shows that the older Highsmith got, the more battles and important moments in Texas history he claimed to have been a part of. The resume padding began in 1877 with a claim that he was in Captain Alley's company during the campaign of fall of 1835. In 1881, he added San Jacinto to his record. By 1895, he had added being a messenger from the Alamo, and in 1897 he went all-out and claimed participation in almost every victorious battle in Texas history, but none of the losses. In 1900, he simply claimed that he was in continuous service in the army of Texas for 10½ years. Not only are his latter claims contradicted or not supported by the documentary evidence, they are contradicted or not supported by his own previous claims going back sixty years.

Highsmith could well have served as a ranger for periods other than those that are documented. The Texas Rangers of the 1830s and 1840s were not exactly known for their administrative efficiency and thoroughness with paperwork. Highsmith himself was illiterate, so he wrote no letters and made no notes of his own. He did not own property or practice a trade, so soldiering may have been his main way of earning a living. It is not the intent of this article to conclude that the entirety of his service to the Republic of Texas was for nine weeks in 1842. That being said, everything about his service from 1836 and earlier is suspicious, and it seems that even with the later period, where his service is documented, he was inclined to tell stories about events he did not participate in as if he were there.

Conclusion: Highsmith could have gone with David B. Kent to Goliad to deliver Houston's letter of March 11, 1836 to Fannin. If he did, he lied about Fannin's reply when telling his story to Sowell. He did not fight at San Jacinto. He may have entered the Texas Rangers in the fall of 1836, following his return to Bastrop. He participated in the removal of General Woll from San Antonio. He was in the U.S. army for twelve months during the latter half of the Mexican-American War.

Retirement

There are no controversies or discrepancies to resolve about Highsmith's later years, but it is nevertheless appropriate in this article to present the documentary evidence. In 1877, Benjamin F. Highsmith applied for a pension from the state of Texas for surviving veterans of the Texas Revolution. As required by the statue, Highsmith swore on his application that he was indigent. His pension application was approved, but the state received ten times more applications than it expected, and the funds were quickly exhausted. Highsmith received a preprinted good news-bad news form from the state comptroller's office informing him that he was enrolled as a pensioner and was due $37.50, but there was no money to pay him. He received one of these forms every quarter.

The legislature passed another pension act in 1878. Highsmith submitted an application in Bastrop County in which he substantiated his indigence by declaring that his entire net worth consisted of two horses, five cows and calves, and twenty-two head of hogs, all of which together were worth 125 dollars.

In 1879, the legislature passed an act in which it reverted to the old system of rewarding veterans: by giving them land. Highsmith submitted an application in 1881, which was approved on October 24. The General Land Office issued a certificate for 1,280 acres in Webb County on April 29, 1882. The patent was issued to Samuel A. Wolcott on April 10, 1883. Highsmith evidently sold this grant before the patent was issued, as he did with his headright grant. Meanwhile, he assigned his pension, which he apparently never got any money from, to a law firm in Uvalde on October 15, 1883. Another preprinted "cannot issue" form was sent out on October 27, 1883.

In 1882, Highsmith moved to Bandera County. It is apparently after this move that he began adding the Alamo to his repertoire of stories. All of his relatives, except his wife, who was not yet born when the Alamo fell, and all of his friends and companions from his ranger days were dead or in Bastrop, so he had free reign to tell his story any way he wanted to, with no one there to correct him. The first recorded instance of a Highsmith claim to have been at the Alamo is from April 1895. He gave a sworn statement for the grand-nephew of Alamo defender R. W. Ballentine that the said man died at the Alamo and was also known as J. J. Ballentine. Highsmith stated "that said Ballentine was the only man by the name of Ballentine in the Alamo or in the army of the Republic of Texas, he being well acquainted with all the soldiers of the Republic of Texas at that time."18 Highsmith's qualification to make that statement was that "he saw him there two weeks before the fall, he having been sent with instructions from Travis to Fannin." Highsmith's claim that he was well-acquainted with every soldier in the Republic of Texas is preposterous. There are over 400 names on the November 1835 "list of men." Fannin had 400 men. There were over 900 Texas soldiers in the battle of San Jacinto. Five years later, when Highsmith was asked to name the men he served with, he could only remember twelve. Furthermore, John J. Ballentine and Richard W. Ballentine were different men, despite Highsmith's sworn expert testimony. Both were killed at the Alamo, both appeared on the casualty lists, and both were posthumously issued land grants. John was a colonist from Pennsylvania who fought in the battle of Bexar in December, while Richard, was a fresh immigrant to Texas from Alabama who arrived at Bexar in January. If Highsmith had been in Bexar all winter, as he claimed, he might not have made that mistake. Even Amelia Williams, who believed everything else Highsmith said, did not believe he could have known and remembered every soldier in the Texas army and counted John and Richard Ballentine as two distinct fallen Alamo defenders.19

In 1887, Highsmith was approved for a pension from the United States for his service in the Mexican-American War.

Andrew J. Sowell interviewed Highsmith in Bandera County in 1897. Sowell wrote that he drew a pension "as a Mexican war veteran and for two wounds."

On January 2, 1899, Highsmith applied for another pension from the state of Texas. That application is stamped, "PAID Jan 5 1899 Comptroller's Office."

Benjamin's wife, Elizabeth, died in Uvalde County on October 7, 1900 at age 64. He died on November 20, 1905 at age 86.

Biography of Benjamin F. Highsmith

The preceding sections have compared the biography of Benjamin F. Highsmith as told by himself in 1900 and by Andrew J. Sowell in 1897 with the thick stack of documentary evidence that goes back to 1828. This comparison shows that the conventional portrayal of Highsmith as an 18-year old Alamo messenger is not supported by the historical record. A biography of Highsmith that places a proper amount of weight on the documentary evidence, as opposed to the claims he made about himself late in life, is as follows:

Benjamin Franklin Highsmith was born on September 11, 1819 in Lincoln County, Missouri to Ahijah M. and Deobra Highsmith. Ahijah was a veteran of the War of 1812. The Highsmith family emigrated to Texas in the company of several other families in January 1827. Ahijah registered as a colonist in Austin's colony in April. He received title to a league of land on the east side of the Colorado River, about halfway between Bastrop and present-day Smithville, in 1831. Ahijah or some of his relatives may have lived in Matagorda for a time, but most of the Highsmith clan resided in Bastrop.

The Highsmith family was in Gonzales when the news of the fall of the Alamo reached that town. As a 16 year old, Benjamin Highsmith may have accompanied David B. Kent to Goliad on March 11, 1836 with a letter from General Sam Houston to Colonel James W. Fannin to destroy the La Bahia fort and fall back to Victoria. Highsmith then returned and joined his family in the Runaway Scrape. After the battle of San Jacinto, in which Ahijah fought as a member of Captain Jesse Billingsly's Mina Volunteers, the family returned to Bastrop.

Benjamin fought Indians in various companies of the Texas Rangers beginning in 1838, if not earlier. He was a member of Captain Billingsly's company of Mina Rangers during the Mexican invasions of 1842 and participated in the removal of General Adrian Woll from San Antonio in September.

Benjamin's father, Ahijah, died in 1845. Benjamin was illiterate and never accumulated much wealth. He received a second-class headright grant in 1839, but grants usually took years to be processed, and he sold his unfinished claim for $50 in 1846. In the 1850 census, he and his mother were living with another family. He is listed as owning $120 worth of real estate.

Highsmith continued serving in the rangers after Texas' annexation to the United States, in the Mexican-American War.

Following the war, Highsmith settled down in Bastrop. In 1853, the day after his 34th birthday, he married 18-year old Elizabeth Turner, a relative on his mother's side. They had seven children. His mother died in 1872.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the Texas legislature passed a series of pension acts to provide for veterans of the Texas Revolution. To qualify, Highsmith claimed to have been part of Captain John Alley's company from the beginning of the revolution at Gonzales through December of 1835, and he submitted affadivits from witnesses to that effect. Captain Alley's company, however was not at Gonzales when the revolution began. Applicants had to provide evidence that they were indigent. Highsmith stated in one application that his entire net worth consisted of two horses, five cows and calves, and twenty-two head of hogs, worth $125 altogether. His pension application was approved, but he received no money from it, due to insufficient funding by the Texas legislature. He then applied for another pension that paid in land, and sold the approved land claim before the patent was issued.

In 1882, Benjamin and Elizabeth Highsmith moved to Bandera County. He then was approved for a pension from the United States for his service in the Mexican-American war and finally got the steady government paycheck he sought.

Highsmith achieved a measure of fame in his old age after Andrew J. Sowell, a nephew of one of his friends from his youth, came out to interview him. In Sowell's article, which was first published in the Galveston Daily News in 1897, Highsmith claimed to have fought in nearly every significant battle in Texas history, going back to the 1832 battle of Velasco. He inflated his age by two years for these stories, allowing him to be 18 at the outbreak of the Texas Revolution instead of 16. Of all the stories he told, the one that caught the most attention was his claim that just before Santa Anna's army arrived at San Antonio, Colonel William Barret Travis sent him with an express message to Fannin at Goliad to order him to blow up the La Bahia fort and come to his aid. The story received broader circulation with the publication of Sowell's book, Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Southwest Texas, in 1900.

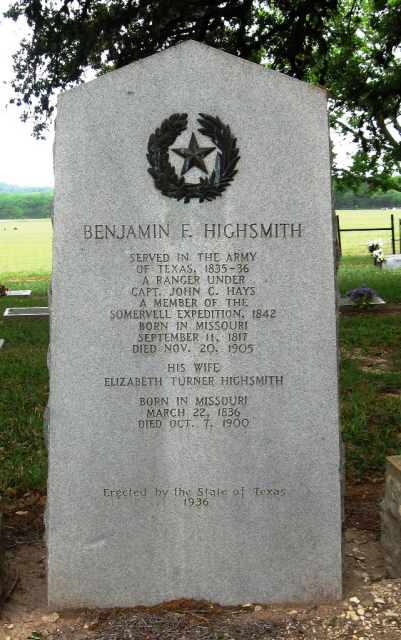

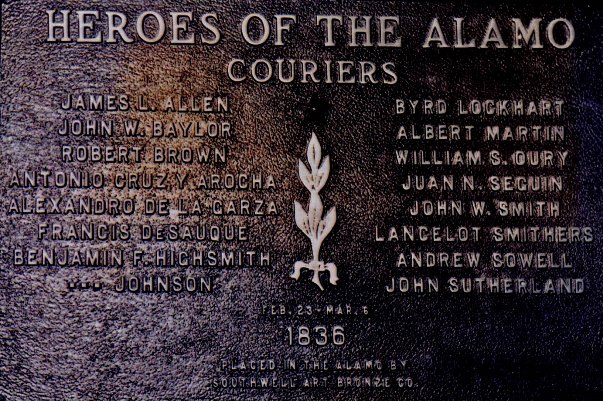

Highsmith died on November 20, 1905 in Uvalde. He was buried in Jones Cemetery, near his retirement hometown of Utopia in Bandera county. In 1931, Alamo researcher Amelia Williams included Highsmith in a list of men she believed left the Alamo as messengers after the siege had started. His name is included on a "Heroes of the Alamo: Couriers" bronze plaque placed in the Alamo in 1936. A granite memorial placed at his grave by the state of Texas in 1936 states that he served in the Texas army from 1835 to 1836, was a ranger under Captain John C. Hays, and was a member of the Somervell Expedition in 1843.

By David Carson

Page last updated: April 30, 2024

1Hansen, doc. 1.7.6.2

2Williams, p. 164.

3Hansen, p. 234.

4Land grant Fannin 2nd-class 154

5Republic claims file 71086, p. 4.

6Republic claims file 71086, p. 3.

7Missouri is sometimes abbreviated as "Miss" in 19th-century records, which could lead researchers astray into thinking he was born in Mississippi.

8Hansen, doc. 1.7.6.2

9Sowell, Andrew J., "Uncle Ben Highsmith."

10This man was Ahijah Highsmith's father-in-law. Also from Missouri, his family was presumably one of the ones that immigrated to Texas with the Highsmiths in 1827. In Austin's register, his name appears right after Ahijah Highsmith's.

11Jenkins, John H. (ed.), Papers of the Texas Revolution, vol. 2, docs. 731, 813, 819, 821, 890, 943, 1064, 1308, 1450.

12Jenkins, vol. 2, doc. 1472.

13Hansen, doc. 3.5.2

14In Texas and the Texans (1841), historian Henry Stuart Foote wrote that Francis DeSauque was the bearer of Houston's express to Fannin. This claim was repeated by Henderson K. Yoakum in 1855. It is doubtful. The first reports of the fall of the Alamo included Desauque as a casualty. If Desauque had been in Gonzales on March 11, it is unlikely that he would have been reported as an Alamo victim.

15Republic donation voucher 380.

16Jenkins, vol. 3, doc. 2319, 2320.

17The documents read "J. L. Sutton," but they refer to John Schuyler Sutton. Copyists often mistook the cursive capital letter S for L, as they looked similar when written by some hands.

18"Notes and Fragments," Texas Historical Quarterly, April 1902, p. 355.

19Williams, p. 246.

- Hansen, Todd (editor), The Alamo Reader, doc. 1.7.6.2, Benjamin Highsmith depositions, 4/2/1900; doc. 3.5.2, letter from Sam Houston to James W. Fannin, 3/11/1836.

- Jenkins, John H. (ed.), Papers of the Texas Revolution.

- Kemp, L. W., "Highsmith, Ahijah M.," Veterans of San Jacinto.

- Smith, Loran, "Remembering the Alamo, and our Bill," Athens Banner-Herald (Georgia), accessed on 2/6/2024.

- Sowell, Andrew J., "Uncle Ben Highsmith," Galveston Daily News, April 8, 1897, p. 8.

- Williams, Amelia, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and the Personnel of its Defenders," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, April 1934.

- Austin's Register of Families.

- "District Court," The Weekly Herald (Weatherford), 4/18/1901, p. 1.

- "List of men who have this day volunteered to remain before Bexar," 11/14/1835.

- Land grant Fannin 2nd-class 154.

- Land grant SC 8:34.

- "The News Briefed", Galveston Tribune, 12/2/1905.

- "Notes and Fragments," Texas Historical Quarterly, April 1902.

- Republic claims file 71086, "Pension Claim Application File: Highsmith, Benjamin F."

- Republic claims file 150795, public debt claim 1291, pp. 1, 66-70.

- Republic donation voucher 380, Kent, David B.

- Republic donation voucher 958, Benjamin F. Highsmith.

- Republic donation voucher 1405, B. F. Highsmith.

- "Texas Revolution Veteran," The Weekly Herald (Weatherford), 4/18/1901, p. 4.

- U.S. Census, 1850, Bastrop County, Texas.

- U.S. Census, 1880, Bastrop County, Texas.

- United States Mexican War Index and Service Records, 1846-1848.

- "The USGenWeb Archives Pension Project."