Charles Despallier, aka Carlos Espalier

Charles Despallier, aka Carlos Espalier

- A Gallant Hero of the Alamo

- Biography of Charles Despallier

- Analysis

- Carlos Espalier

- Texas Land Grants Overview

- Luzgarda Grande's Petition

- "A Mistake"

- The July 1856 Affidavits

- Historians Weigh In

- "A Young Mexican Boy of San Antonio"

- "They Were At Least First Cousins"

- A Summary of the Evidence

- Conclusion

A Gallant Hero of the Alamo

On February 25, 1836, the Texians inside the Alamo were in the third day of the Mexican army's siege. Morale was high. Even though the Mexicans caught them by surprise two days earlier, and the scramble to get inside the Alamo's walls had been chaotic, the men who had families in San Antonio de Bexar managed to get them inside. The Texians' months-long project of turning the old Spanish mission into a proper fort had not been completed, but all of the cannons in Bexar had been brought inside, and many of them had been mounted on top of the walls. Perhaps most importantly, the Texians managed to wrangle a herd of cattle on their way in. If nothing else, they would not starve. Even though cannon fire and gunfire had been traded back and forth for two days, the Texians had suffered no casualties. Thanks to the superior range of the Texians' long rifles, and the Texians' proficiency with them, the Mexicans had been unable to get close enough to the walls to do any damage with their muskets and light artillery. Although they were severly outnumbered, the Texians knew that they could hold out for a few more days, until help arrived from Golaid and Gonzales, at which time the Mexicans would have a different kind of fight on their hands.

The impatient Mexican commander, Generalissimo Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, did not want to waste time with a lengthy siege. He had hoped that his cavalry brigade would rush into town so quickly as to cut the Texians off from the Alamo and keep them from holing up in it. He blamed his cavalry commander, General Sesma, for the failure of that plan. It was time for a new plan. At 10:00 a.m. on the 25th, Santa Anna ordered an assault. A battalion of two to three hundred soldiers crossed the San Antonio River, which separated the Alamo from the town of Bexar. Between the river and the Alamo was a little village of wooden huts, or jacales. Taking cover in the huts, the Mexicans opened fire. If they could hold that position, they could set up a battery there and begin doing some damage to the Alamo's walls. The Texians answered the advance with brutal discharges of grapeshot from their cannons, punctuated with accurate rifle fire. After a two-hour struggle, the Mexicans retreated, dragging their dead and wounded with them back across the river. The Texians collected a few scratches from shards of rock that broke off the walls, but were otherwise uninjured.

The Texians' commander, Lt. Colonel William Barret Travis, wrote a letter about his victory to Sam Houston, the commander-in-chief of the Texas army. As any good commander would, he praised the soldiers who were under his command that day, which numbered about 150. While admitting that it was unjust to leave anyone out, he nevertheless commended six of his men by name. One of those six was 20-year-old Charles Despallier. Of him, Travis wrote:

Charles Despallier and Robert Brown gallantly sallied out and set fire to the houses which afforded the enemy shelter, in the face of the enemy's fire.

Excerpt from William B. Travis, letter to Sam Houston, 2/25/1836 (Hansen, doc. 1.1.5)Charles Despallier was not one of the most well-known men at the Alamo, by any standard. He was not nationally famous, like David Crockett, nor was he a local legend, like James Bowie. He was not frequently mentioned in the news, like Travis, nor was he a respected officer in the Texas militia, like Juan Seguin and Albert Martin. He was not even a longtime resident, like Almeron Dickinson. He had been in Texas for at most four months. The only way people might have known of him is through his brother or father, who had also spent brief periods in Texas, or through his friendship with Bowie. But when the first rumors that the Alamo had fallen began to trickle into Gonzales between March 11 and March 13, Despallier's name was mentioned along with Travis, Bowie, Crockett, and Dickinson. The rumor at the time was that many of the Alamo defenders committed suicide. Here is what Sam Houston wrote about it:

Our friend Bowie, as is now understood, unable to get out of bed, shot himself, as the soldiers approached it. Despalier, Parker, and others, when all hope was lossed [sic] followed his example. Travis, tis said, rather than fall into the hands of the enemy, stabbed himself.

Excerpt from Sam Houston, letter to Henry Raguet, 3/13/1836 (Hansen, doc. 3.5.5)Charles Despallier has the distinction of being one of only two Alamo defenders to be mentioned in writing after the beginning of the Alamo siege by both William Barret Travis and Sam Houston (the other being Dickinson). He also has another distinction: most 20th and 21st-century lists of Alamo defenders, including the one on the official Alamo web site, include him twice—first as Charles Despallier, and again as the Spanish version of his name, Carlos Espalier.1 This article presents a biography of Charles Despallier and explains how his alter-ego, Carlos Espalier, came into being.

Biography of Charles Despallier

Charles Despallier was born in December 1815 into a family of Texas revolutionaries. His father was Bernard Martin Despallier, a Frenchman who settled in Louisiana when it was under Spanish control. Bernard had a career as an officer in the Spanish army in Rapides Parish that came to an end when Louisiana passed back into French, and then American, hands. As a loyal Spaniard, he emigrated to Spanish Texas. There, he married a Tejana, Maria Candida Grande. A general mistrust of immigrants from the east worked against him in his short-lived military service as well as his business dealings. His position worsened in 1808, when Spain and France went to war. Forced to leave Texas simply because of his French origins, he moved back to Louisiana. Disillusioned, he joined Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara and Augustus Magee in their filibustering expedition, which was intended to separate Texas from the Spanish Empire.

After the Gutierrez-Magee Expedition entered Texas, Bernardo de Espalier, as he was known west of the Sabine, enlisted the aid of his father-in-law, Louis Grande, in distributing propaganda pamphlets to the Tejanos of San Antonio de Bexar. Grande was caught and, most likely, executed. Espalier stayed with the expedition up to its victory over the royalists at the Presidio la Bahia in Goliad. He then went home to Louisiana, for unknown reasons. The insurgents were then decisively defeated at the Battle of Medina on August 18, 1813, ending that particular Texas independence movement.

Bernard Despallier, as he was once again known, settled in Rapides Parish with his wife and family. In December 1815, they had their fourth son, Joseph Charles Martin Despallier. Their first son, Jose, died at the age of seven. As of the 1820 U.S. Census, the family consisted of Bernard, 46; Maria Candida, 29; Blaz, 10; Victor, 7; and Charles, 4.

In 1824, a land grant fraudster named James Bowie moved to Alexandria, the seat of Rapides Parish. Bowie always needed accomplices to buy or sell his fictitious land grants, to create a paper trail and give them an appearance of legitimacy. In Rapides Parish, Bowie found a partner in Bernard Despallier. Eventually, the whole Despallier clan became involved with Bowie. After Bernard died, Victor Despallier took over as Bowie's land agent in Rapides Parish. In 1834, Blaz joined Bowie on a journey to Monclova, Coahuila, where Bowie hoped to capitalize on the land speculation fever swirling around the state capitol. While they were there, President Santa Anna sent General Martin Perfecto de Cos to crack down on the federalist Monclova Congress. Bowie and Blaz Despallier were found in the company of the deposed governor, Agustin Viesca, and were arrested. They escaped together from a Matamoros jail on June 12, 1835 and made their way back through Texas to Louisiana. In a letter Bowie wrote during a stop when Blaz was sick, Bowie called him his "traveling companion."2

The date of Charles Despallier's arrival in Texas is unknown, as is his relationship with Bowie. Given Bernard, Blaz, and Victor's documented associations with him, one must assume that Charles knew him from an early age. It is possible that he left Louisiana with Bowie in late September or October 1835. Bowie went to Goliad in the first week of December. Charles Despallier is documented to have been in Goliad on December 20, when he joined ninety other men in signing a declaration of independence from Mexico more than two months prior to the formal declaration issued at Washington-on-the-Brazos. In January, both men were in Bexar. There, Despallier was known as a companion or aide to Bowie, and was even heard to call him "Uncle" on at least one occasion. It would not be going out on a limb to speculate that he traveled with Bowie from Goliad and arrived with him in Bexar on January 19.

Charles Despallier's brother, Blaz, also fought in the Texas Revolution. Prior to his sojourn to Monclova with Bowie, Blaz had owned a newspaper in which he had published an editorial supporting the U.S. annexation of Texas. On November 1, 1835, he joined Captain Thomas H. Breece's company of the New Orleans Greys as it marched through Natchitoches. He arrived outside Bexar on November 26, 1835, the same day as the Grass Fight. He fought in the Battle of Bexar, which lasted from December 5 to December 10, 1835. A few days later, he became ill and was discharged. He then went home to Louisiana. Blaz sold his land grants from the Texas Revolution to Justin Costanie for 550 dollars cash. He died of an illness in 1839.

Charles Despallier may have gone to San Felipe and returned to Bexar with Lt. Colonel Travis in early February. He was in Bexar when the Mexican army arrived on February 23, and he entered the Alamo with the other Texians.

The Alamo battle for which Travis praised Despallier's bravery took place on February 25. He may have left the Alamo shortly after this event. If he did, he returned with the Gonzales relief force on March 1. He was killed in the battle on March 6. In addition to his death being reported by Sam Houston, his name appeared on all three early Alamo casualty lists—the one made out by William Fairfax Gray on March 20, 1836, the one printed in the March 24 issue of the Telegraph and Texas Register, and the one maintained by the Texas adjutant general, which the Texas General Land Office used to validate land claims. Two of those lists referred to him as an aide to Travis; the other gave him the rank of lieutenant.

Bernard Despallier's remaining son, Victor, died in the 1840s.3 His son, Blaz Philipe Despallier II, went to live with his grandmother and Charles's mother, Maria Candida Grande Despallier. She filed for Charles's Texas Revolution benefits in 1851. In that year, she was awarded a first-class headright grant, a donation grant, and a certificate for sixty dollars in payment for Charles's service to the Texas army from October 1, 1835 until his death in the Alamo battle on March 6, 1836. Maria Candida died in 1852, leaving ten-year-old Blaz Philipe II as Charles's only surviving heir. The estate was awarded a bounty grant in 1854. The patents for Charles's land grants were issued to Blaz in 1855.

In 1855, Luzgarda Grande of San Antonio petitioned the Texas legislature for the benefits due, as the only surviving heir of her nephew, Carlos Espalier, for his death in the Alamo battle. The legislature passed a special act recognizing Carlos Espalier as an Alamo defender and awarding him headright, bounty, and donation grants. Governor Elisha M. Pease signed the act, but immediately noticed that grants had already been issued to Charles Despallier. Believing them to be the same person, Pease asked the legislature to reconsider the matter. After Mrs. Grande submitted more evidence, she was allowed to keep her grants. Alamo historians for the next 75 years, however, did not accept Carlos Espalier as a valid Alamo defender. This changed in the early 1900s, after researcher Amelia Williams misread the affidavits in the Carlos Espalier file as saying that he was a "young Mexican boy of San Antonio" and concluded that he and Charles Despallier were two different people. This mistake has been repeated and perpetuated ever since, even after Despallier biographer Rasmus Dahlqvist presented conclusive evidence in 2013 that Charles's mother, Maria Candida Grande, and Carlos's aunt, Luzgarda Grande, were sisters.

Analysis

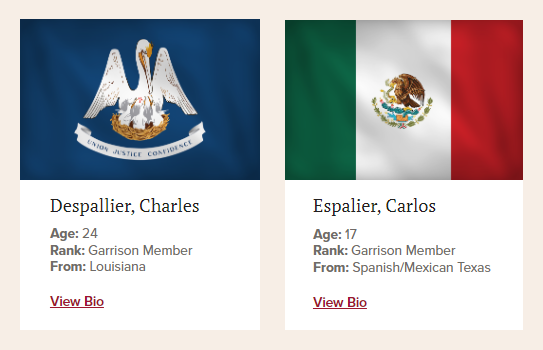

As shown in Figure 1, above, Charles Despallier's age as of the date of the Alamo battle is usually given as 24. This was the age that Amelia Williams pulled out of thin air in her 1931 doctoral thesis, "A Critical Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of Its Defenders." Subsequent Alamo historians, having no documentation to go by, have used Williams's guesswork age by default. In his 2013 biography of the Despallier family, From Martin to Despallier, Rasmus Dahlqvist used baptismal records of St. Francis Catholic Church in Natchitoches, Louisiana to build an accurate biographical profile of Bernard Martin Despallier's whole family. According to his baptismal certificate from in April 1816, Joseph Charles Despallier was born in Rapides in December 1815. This would make him 20 on the day of the Alamo battle.

Dahlqvist notes that Charles Despallier could possibly have visited Texas with James Bowie in 1831. In the fall of that year, Bowie, his brother, Rezin, and a group consisting of eight men and a boy named Charles went out from Bexar to look for the lost San Saba silver mines. They were attacked by natives. One of the men was killed. The rest of the party returned to Bexar on December 6. Charles would have been turning 16 at about that time, so it is conceivable for him to have been the boy Bowie referred to. On the other hand, historian James T. De Shields, under the assumption that anyone in 19th-century Texas who was referred to only by his or her first name was black, wrote that the Charles on this trip was a Negro servant. Whether he was, in fact, Charles Despallier, a black servant, or someone else is pure speculation.

Even though Charles Despallier's first confirmed appearance in Texas is his signature on the Goliad Declaration of Independence, dated December 20, 1835, there are signs that he had been in Texas for over two months by then and that he had previously been to Bexar. His bounty grant indicates that his service to the Texas army began on October 1, 1835. This could have been an approximation or guess; the certificate had a blank for a date for a date to be filled in, and so a date was filled in. Alternatively, that date could have been supplied by the applicant, Maria Candida Despallier, referring to the date Charles left home. It so happens that Bowie left Louisiana at about the same time.4 There are two sources that place Charles and Blaz Despallier together in Bexar. Justin Costanie, who bought Blaz's land grants, wrote in 1856 that he met Blaz while he was on his way back home to Natchitoches in January 1836 and Blaz told him "he left [Charles] in the army at San Antonio."5 French painter Theodore Gentilz wrote that the Bexar woman known as Madam Candelaria told him that she cooked for "two French brothers from Nacogdoches, the brothers Despallier."6 Both Costanie and Gentilz's statements are hearsay, so caution is advised in using them for analysis, but they may contain some truth. The documents show that Blaz arrived at Bexar on November 26 and was discharged on December 13, while Charles was apparently not in Bexar as of December 5 and was in Goliad on December 20. That gives us about a week of possible overlap in late November and early December. Coincidentally—or perhaps not—Bowie was in Bexar on November 26 but left for Goliad before December 5. Most of the pieces of Charles Despallier's itinerary fall into place if we assume that he was a traveling companion of Bowie in 1835, just as his brother had been a year earlier.

Charles Despallier is usually included among the "Immortal 32" men who reinforced the Alamo on March 1, 1836. The basis for his inclusion in this group is an article published in the Texas Historical Association Quarterly in 1899. In the article, which is about the Battle of Gonzales, Miles S. Bennet recalls the names of 26 men who "went from Gonzales" to the Alamo, and includes Despallier in that list. Bennet does not claim that all 26 of these men rode in with the March 1 relief effort, however, and in fact, two of them—Almeron Dickinson and Amos Pollard—certainly did not. Still, Bennet had to have included Despallier for some reason, and since Despallier, unlike Dickinson and Pollard, was not from Gonzales and had no other known connection to the town, it is hard to think of any reason for including him unless he went with the Gonzales relief force. Williams is much less tentative about the issue, declaring, "he entered the Alamo on March 1 with the famous thirty-two from Gonzales. Conclusive documents state this fact." In reality, the one source we have, Bennet's article, is not only inconclusive; it isn't even a document.

The most likely date of the Gonzales men's departure from Gonzales is February 27. Since Despallier was involved in the action at the Alamo on February 25, the earliest he could have been in Gonzales is February 26, meaning he spent only one day there. Perhaps when he "sallied out" of the Alamo to burn the huts, he did not return back inside, but instead rode on to Gonzales. If so, his news of the Texians' victory that day, and his excited description of the part he played in it, might have given some of the men the motivation they needed to join the group. The impression he made during his short time in town may explain why Houston wrote about him from Gonzales on March 13 and why Miles Bennet recalled his name 63 years later.

Because he may have left the Alamo and returned, Alamo historians and references usually refer to Despallier as a "courier," which means the purpose of his departure was to carry a message or item. This is speculative. We do not even know for certain that Despallier left the Alamo, much less the circumstances or reason.

Carlos Espalier

Charles Despallier's aunt, Luzgarda Grande, filed a petition with the Texas legislature in October 1855, stating as follows:

County of Bexar

Personally came and appeared before me the undersigned authority Maria Lus Guarde Grande who after being duly sworn from her oath says that she is the only living heir of her nephew Carlos Espalier who fell as a Texan Soldier while defending the Alamo together with Bowie and Crockett and that the said Carlos Espalier has never obtained any Land or pay from the Government of Texas nor has she ever obtained any as heir of the said Espalier nor has any other person for the said Espalier or her as heir.

Lus Guarde Grande

[notarized on October 5, 1855]

Lus Guarde Grande sworn statement, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.Texas Land Grants Overview

Before examining Grande's petition, it is appropriate to explain the three different kinds of land grants that were available to fallen Alamo defenders. The first kind, the first-class headright, was promised by the Texas Constitution as follows:

All persons (Africans, the descendants of Africans, and Indians excepted,) who were residing in Texas on the day of the declaration of independence, shall be considered citizens of the republic, and entitled to all the privileges of such. All citizens now living in Texas, who have not received their portion of land, in like manner as colonists, shall be entitled to their land in the following proportion and manner: Every head of a family shall be entitled to one league and labor of land; and every single man of the age of seventeen and upwards, shall be entitled to the third part of one league of land.

Constitution of the Republic of Texas, General Provisions, sec. 10 (Gammel, Laws of Texas, vol. 1, pp. 1079-1080).The Texas Declaration of Independence was signed on March 2, 1836. Since all fallen Alamo defenders were in the Alamo by March 1 and none were black or Indian, all those who were at least seventeen by March 2 were eligible for this grant.7

The other two kinds of grants were bounty grants and donation grants, which were rewards for military service. Bounty grants were issued based on a man's length of service in the Texian army. The size of the grant depended on how many months the man served, up to the maximum of 1,280 acres. Often, but not always, a man who died in battle was granted the full 1,280 acres, and in many Alamo claims, a 640-acre "adjustment" was added, making a total of 1,920 acres. Donation grants of 640 acres were issued for participation in specific battles of the Texas Revolution, the Alamo being one of them. All fallen Alamo soldiers were eligible for both bounty and donation grants. Those who had not already received a headright grant prior to their deaths were eligible for all three grants.

The procedure for applying for a land grant was different than it would be today. Instead of filling out a form and attaching documentation to support their claims, applicants went before a notary public and made a sworn statement, affirming that their claim met the requirements of the law. If the applicant had any witnesses who could vouch for them, they made their own sworn statements. In the vast majority of Alamo claims, this was all the evidence claimants had. Most land grants were submitted for approval to either a local board of land commissioners or the state Court of Claims, but Luzgarda Grande submitted her petition during a period when claimants had to go directly to the Texas legislature.

If the reviewing body found that a claim appeared to meet the legal requirements, the General Land Office had to confirm that no grants had previously been issued on behalf of the same claimant. After everything was found to be in order, a grant certificate was issued. This certificate was actually just an authorization for the grantee to have a survey made in a particular county. It generally took several years for the survey to be completed, any disputes or issues to be resolved, and for the grant to be patented, at which point it was official and final. Many grantees were uninterested in becoming settlers or farmers and simply wanted cash, so it was common for grantees to sell the grants before they were patented.

Luzgarda Grande's Petition

Grande was illiterate. Her paperwork was prepared by her son-in-law, Malcolm G. Anderson, who married her daughter, Trinidad Garcia, in 1854. Grande submitted five affidavits with her petition. The first two were from Francisco Antonio Ruiz, a person well-known to Alamo history buffs as the alcalde of Bexar at the time of the Alamo siege and battle. His statements read:

County of Bexar

Before me the undersigned authority, personally appeared Francisco A. Ruiz who on his oath says, that Carlos Espalier, who was to this affiant well known, fell fighting in the Alamo with Bowie and Travis and under their command, that he was killed by the Mexican Soldiers while fighting by the side of Bowie for the liberties of Texas, and his remains were buried among those of the Texians and as a Texian: that said Carlos Espalier was known to the affiant before the storming of the Alamo, and that he was Engaged on the Side of Texas and was one of the defenders of the Alamo.

Fran. A. Ruiz

[notarized on October 22, 1855]

Francisco Ruiz sworn statement (1st of 2), Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.County of Bexar

Personally came and appeared before me the undersigned authority, Francisco A Ruiz who after being duly sworn, according to law, upon his oath says, that Carlos Espalier was a resident citizen of the Republic of Texas before the 2d of March AD 1836, the day of the date of the declaration of Independence. Affiant further states, that the said Espalier was upwards of Seventeen years of age at the said date of the Declaration of Independence, that the said Espalier was a Single man, and did not leave the Country to avoid a participation in the Struggle for the independence of the Same.

Fran. A. Ruiz

[notarized on October 22, 1855]

Francisco Ruiz sworn statement (2nd of 2), Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.The first affidavit satisfies the requirements of Espalier's bounty and donation grant claims. Its emphasis on Espalier fighting on the Texian side is unusual—perhaps even unique—among Alamo defender grant applications. At that time, no Tejano or Spanish-surnamed Alamo defenders had been identified, even though it was common knowledge that Tejanos fought in the Texas Revolution. Obviously, Grande and Anderson wanted to make it clear to the legislature that Carlos Espalier fought on the side of Texas, not Mexico. The second statement pertains to Espalier's headright claim. It is mostly a boilerplate repetition of the law's requirements and Ruiz's affirmation that they were met.

The next two sworn affidavits in Grande's petition were from Juana Navarro, another person who is well-known to Alamo history buffs. Navarro was the adopted sister of James Bowie's late wife, Ursula Veramendi, making her Bowie's sister-in-law. She was also known to be one of the few noncombatant survivors of the Alamo battle, meaning she was inside the Alamo walls during the entire thirteen-day siege. Her affidavits read virtually identically to those sworn by Ruiz. The word-for-word match between Ruiz's and Navarro's statements indicates that they did not compose them themselves, but were given statements to sign that were prepared in advance by Anderson or someone else. This was an entirely normal and acceptable practice, for it was the best way for claimants to get the exactly evidence they needed—no more, no less, and no surprises.

With the legal requirements of Espalier's land grant claims attested to by two reputable witnesses, Grande still needed to prove one more thing, which was that she had the right to file the petition on behalf of the late Espalier as his legal heir. Here, she supplied the affidavit of Gertrudes Rivas, whose relationship to Grande and the Alamo is unknown:8

County of Bexar

Personally came and appeared before me the undersigned authority, Doña Gertrudes Rivas who after being sworn upon her oath says that Carlos Espalier was to her well known and she farther [sic] says that the said Espalier was the nephew of Señora Lus Guarde Grande of the City of San Antonio. affiant further states that to the best of her knowledge and belief Señora Lus Guarde Grande is the only living heir of the said Carlos Espalier deceased.

Gertrudes Rivas

[notarized on October 25, 1855]

Gertrudes Rivas sworn statement, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.Anderson knew that the legislature would check with the General Land Office to see whether any land grants had been issued to Carlos Espalier, so he did his own due diligence prior to submitting Grande's petition and received a statement from the land office commissioner confirming that none had. With everything in order, he presented the petition to the legislature. On July 16, 1856, the legislature passed the special act below, which Governor Elisha M. Pease signed into law the next day:

Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Texas, That the Commissioner of the General Land Office be, and he is hereby required to issue to the heirs and legal representatives of Carlos Espalier, who was killed at the Alamo, a certificate for one-third league headright, nineteen hundred and twenty acres bounty, and six hundred and forty acres donation lands, amounting to four thousand and thirty-six acres; which said certificate, or certificates, to be located, surveyed, and patented according to law. And that this act take effect and be in force from and after its passage.

Approved July 16th, 1856.

Special Laws of the Sixth Texas Legislature, Chapter 86 (Gammel, vol. 4, p. 549).

"A Mistake"

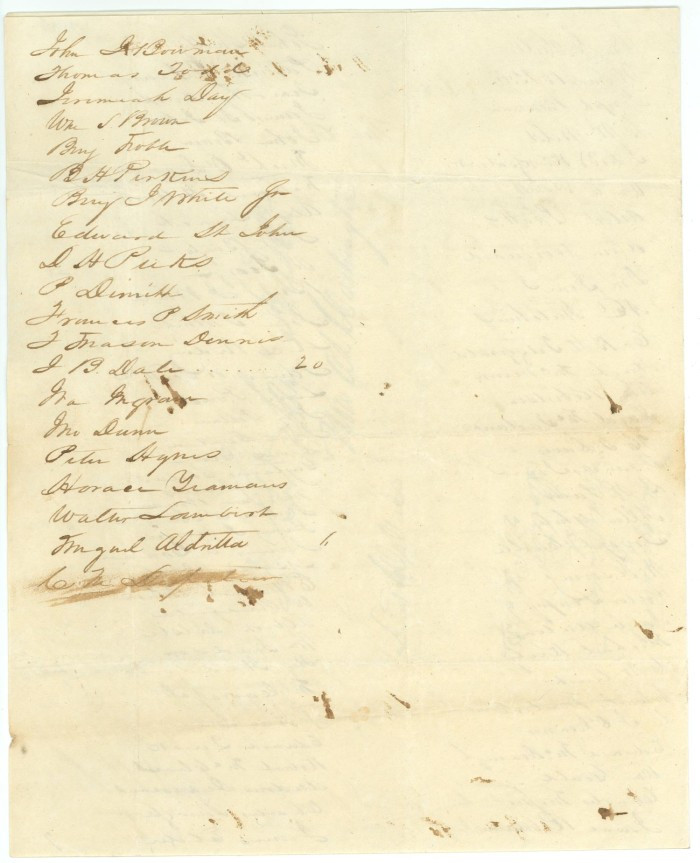

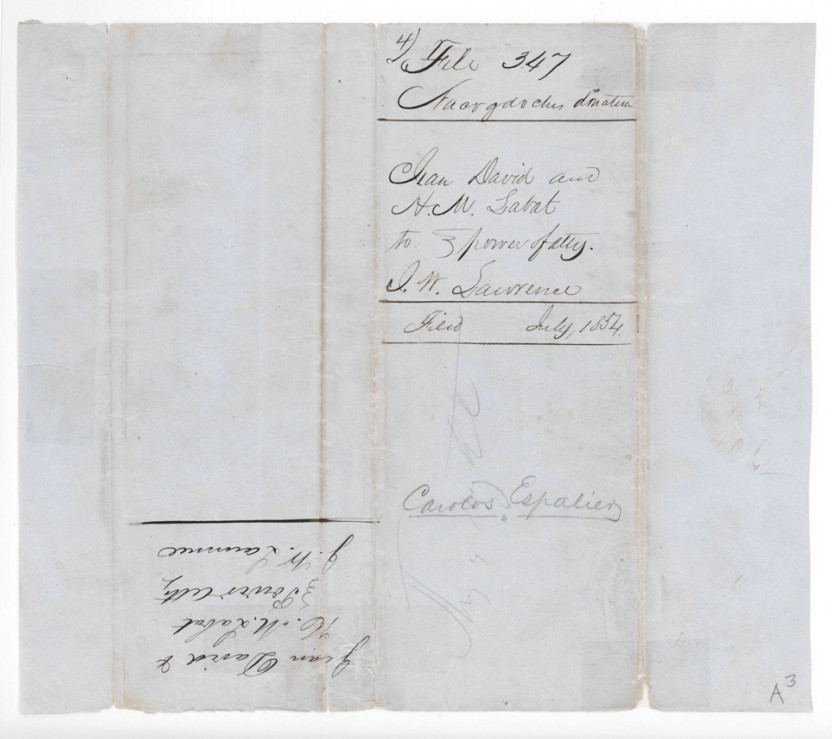

There was a problem with Grande's grants immediately. In July 1854, Jean David and H. M. Labat, representatives of Blaz Despallier II, the minor heir of Charles Despallier, sent a letter to their Austin attorney about Charles's donation grant, which had been approved, but not yet patented. The letter was filed at the General Land Office under the name Carlos Espalier and placed into Charles's file for Nacogdoches Donation 347. This occurred a year before Grande and Armstrong began working on their petition to the legislature and two years before the special act was passed. So, it turned out that when an inquiry was made for grants issued to Carlos Espalier, the employees at the land office missed this document, probably because they did not think to look in Charles Despallier's files. If they had, they would have found that a grant had already been made to Carlos Espalier.

Whether this evidence was brought to Governor Pease's attention, or whether for other reasons, two days after he signed the special act into law, he wrote the legislature:

Executive Office

Austin Texas

19th July 1856

Gentlemen of the Senate

and House of Representatives

on the 17th instant an Act from for the relief of the heirs of Carlos Espalier, which had previously passed both houses of the Legislature, was approved by me. By this Act Four Thousand and thirty six acres of land were granted to the heirs of said Carlos Espalier, for his Head right, bounty and donation land in consideration of his having been Killed at the Alamo under the command of Travis.

Since this Act was passed I have learned that a like quantity of land had been previously obtained from the State, by the heirs of Charles Despalier, for his Head right, bounty and donation land, as one of those who fell at the Alamo under the command of Travis.

Facts have come to my Knowledge that induce me to believe that Carlos Espalier and Charles Despalier were one and the same person, the former being the name by which he was called by the Mexicans and the latter by the Americans.

I am also induced to believe that the party who applied for and obtained this last grant to the Heirs of Carlos Espalier, was acting under a mistake in regard to her being the heir of Carlos Espalier, and also in supposing that no land had been previously obtained for his services.

...

I am well satisfied that the applicants for both of these grants were claiming as heirs of the same person, and that the last grant has been improperly issued.

I respectfully recommend that you cause this matter to be investigated, and if the facts here stated are found to be true, that An Act be passed repealing the last grant, and cancelling the certificates issued under it.

E M Pease

Letter from Elisha M. Pease to the legislature, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.Texas newspapers picked up the story, calling it "one among many instances of past sessions, where unworthy claims have been passed."9

An embarrassed M. G. Anderson wrote a letter to the legislature assuring the members that he did not intend to mislead anyone. He explained that before submitting Grande's petition, he obtained a certificate from the commissioner of the General Land Office that Carlos Espalier had not previously been issued land. Even so, he did not concede that his mother-in-law's claim was invalid. "I do not deny that Charles Despalier is entitled to land," he wrote, "but... Carlos Espalier is also entitled to land."10 He then began obtaining a new set of affidavits in an attempt to salvage Grande's claims.

The July 1856 Affidavits

Anderson's letter to the Texas House indicates that his initial reaction to governor's letter was that Charles Despallier and Carlos Espalier were not the same person: Carlos Espalier died at the Alamo and was entitled to land, and if there was also a Charles Despallier who died at the Alamo and was entitled to land, then so be it, but that did not change the validity of Espalier's claim. Anderson's next strategy was to offer evidence that Despallier and Espalier were not, as Pease asserted, the American and Mexican name for the same man, but that they were two different people. To that end, he used the services of a San Antonio attorney named A. H. Davidson, who obtained affidavits from four men—Agustin Berrera, Francisco Granada, Juan A. Urutia, and Cayetano Rivas.11 The facts these men swore to are as follows:

- All four men swore that they were well-acquainted with Carlos Espalier, who fell at the battle of the Alamo, that he was a companion of James Bowie, and that he was not known as Charles Despallier.

- Berrera and Rivas additionally swore that Luzgarda Grande was Espalier's aunt—specifically, his mother's sister—and sole heir.

- Berrera additionally swore that he "went in Company with the Priest to the Alamo and there saw the dead body of the said Carlos Espalier."12

- Rivas additionally swore that Espalier "remained some time" at his home in San Antonio before the fall of the Alamo and that he knew him "as well as he did one of his own children."13

The above statements covered the required elements that Grande and Anderson were looking for, but there was a potential problem in that none of the affiants would have been recognized by the members of the legislature. When Davidson sent the affidavits to Anderson, he wrote that if someone needed to vouch for the affiants, "Mr. Maverick"—Samuel A. Maverick, a former mayor of San Antonio who resided there in early 1836—could do so. Davidson also advised Anderson that another potential affiant, Jose Antonio Menchaca, was in Austin at that time. Menchaca was another resident of San Antonio in 1836, another former mayor of San Antonio, and an honored veteran of the Battle of San Jacinto. The legislators would know him, or at least know who he was. Getting his testimony would give Grande's petition substantial credibility.

Menchaca did give a statement on Grande's behalf. It is quite different from all of the other testimonies in the Espalier file. It is not a prepared statement that he signed; it is his own story, in his own words. It reads:

Statement of Antonio Menchaca in the matter of the issuance of the certificate to the heirs of Carlos Espalier.

In the month of January 1836 ^in San Antonio^, I was with James Bowie when Carlos Espalier came into ^the [illegible] room^ and said to Jim Bowie, ^“uncle,^ come and let us go to supper.” I went with them to the house of Luz Garde Grande while there Carlos Espalier addressed her as Mother I asked him why he called this old Woman Mother He replied ask her yourself why. I addressed the question to the old woman—she answered why not, He is the son of my own sister Mariana Grande—Luz Guarde Grande and her sister Mariana Grande were daughters of Louis Grande of Nacogdoches. I continued to be acquainted with Carlos Espalier to the 17th of Feby 1836 when at the coming of San Anna with his invading army, I left with my family to take them to take to a place of safety—and I know positively that Carlos Espalier went in with others to the Alamo and was killed there in the fall of that place.— I knew all the men were in the Alamo with the Travis but cannot now recollect all their names—There was no such man there as Charles Despalier—or Carlos Despalier—Carlos Espalier was the aid of Bowie. I never had any talk with Bowie in regard to him. From conversations with Carlos Espalier I learned that some of his relations were living in Louisiana in the Parish of Rapide or Altarapa[?], which I am not certain—

I do not know whether at that time the mother of Carlos Espalier was living or not—I never heard Carlos Espalier say anything about his mother—who she was or where she lived—or whether she was living or dead except what has been before stated in the conversation herein first alluded to—The only relations of said Carlos Espalier known to me were Luz Garda Grande, and her son and daughter Mariana Garcia and her daughter Trinidad Garcia, the present wife of M G Anderson—I heard always heard him called Carlos Espalier and by no other name—Has seen him frequently sign his name Carlos Espalier in Castilian.

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this 28th day of July 1856 Antonio Menchaca

M L [illegible]

Sworn statement of Antonio Menchaca, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856. Text that appears ^in between carats^ was inserted between the lines of the main text.

Menchaca made numerous assertions in this statement that are not found in any of the others, including that Espalier referred to as Luzgarda Grande as "Mother" and Bowie as "Uncle," that Grande was an old woman, that Espalier's mother's name was Mariana Grande, that Luzgarda and Mariana were the daughters of Louis Grande of Nacogdoches, and that some of Espalier's relatives (although not necessarily his mother) lived in Louisiana, possibly in Rapides Parish. From what we now know about Charles Despallier's biography, it is obvious that he and Carlos Espalier were the same person. The connections to Rapides Parish and Louis Grande—Charles Despallier's maternal grandfather—are the most obvious ones. Charles's father, Bernard, died sometime around 1825,14 when Charles was ten, and given how closely his brothers were associated with Bowie, calling him "Uncle" would be understandable. The only real discrepancy between Menchaca's biography of Espalier and the known biography of Despallier is that Despallier's mother's name was Maria Candida, not Mariana. Perhaps Luzgarda called her Mariana as a nickname, or perhaps Menchaca confused Luzgarda's sister's name with that of her daughter, Mariana. Menchaca admitted he did not know much about Espalier's mother. He may have only heard her name mentioned one time, so the mistake could easily have been his.

Menchaca does seem to have made a mistake in calling Luzgarda Grande an "old woman." She was about 46 when this conversation took place.15 Menchaca was 36. Certainly, this would not be the first time that a person in his or her forties was described as old by someone in his thirties, but this apparent slip-up does cause one to wonder how much of this interaction Menchaca remembered correctly.

A more glaring error with Menchaca's statement is where he declared that he knew all of the men in the Alamo and "there was no such man there" as Charles Despallier. Menchaca's statement here that he left Bexar on February 17 corresponds roughly with a story he later told of first hearing about the arrival of the Mexican army about six days after he left.16 Even if we give him the benefit of the doubt that he knew all of Colonels Neill, Bowie, and Travis's men, would he really have known all of the fresh arrivals from Tennessee and Kentucky who arrived with David Crockett on February 9, and all of the Gonzales men who arrived on March 1? And, of course, there was a Charles Despallier at the Alamo. Travis and Houston both mentioned him. M. G. Anderson told the Texas legislature he was not arguing that Charles Despallier did not die at the Alamo, but now his star witness swore to exactly that. This is why land grant claimants usually gave their witnesses prepared statements to sign instead of letting them write their own testimonies.

When Governor Pease and the newspapers voiced their objections to Grande's Carlos Espalier claims, they gave her the benefit of the doubt that she had no intention of committing fraud; she had made an innocent mistake. It is hard to extend that gracious interpretation to Grande and Anderson's subsequent actions, however. Menchaca said that Carlos Espalier had relatives in Louisiana; had anyone made any effort to contact them or to find out who they were, to confirm whether Luzgarda truly was Espalier's only surviving heir? Apparently not. And why did Grande and Anderson need new witnesses to swear that Carlos Espalier did not go by the name Charles Despallier? Where were their reputable witnesses, Francisco Ruiz and Juana Navarro, who testified nine months earlier? As Bowie's sister-in-law, Navarro probably knew Espalier better than any of the witnesses. Did, perchance, Grande and Anderson ask Ruiz and her whether Espalier went by Despallier, and they did not give them the answer they wanted, which is why five new witnesses had to be brought into the case?

Grande and Anderson took a big risk by submitting Menchaca's affidavit along with their petition, because it contained a statement that was obviously false, and that no one would believe—that an Alamo defender named Charles Despallier did not exist. Fortunately for Grande, there was no harm done. There are no more documents in the record about the legislature's inquiry into the Carlos Espalier matter, but in the end, the special act was not repealed, so the grants issued to Grande remained in force. Upon receipt, she promptly sold them to Anderson, who resold them to a third party.

Historians Weigh In

The Texas legislature may have passed a law in 1856 finding that Carlos Espalier died defending the Alamo, but the people who kept lists of Alamo defenders did not go along with that finding. The 1860 edition of the Texas Almanac published a list of Alamo defenders that included Charles Despallier, but not Carlos Espalier. Truthfully, that list had quite a few surprising omissions, including James B. Bonham and Amos Pollard, and it contained no Spanish surnames at all, so perhaps we should not read anything into Espalier's omission from it. More significant is the list that Elisha Pease, who made keeping an Alamo defender list a personal project of his well after leaving the governor's mansion, promulgated in 1876. By today's standards, Pease's list was neither very complete nor accurate, but it was the best list to date, and, significantly, it included the names of seven Tejano Alamo defenders. Unsurprisingly, Carlos Espalier was not one of them. Historian John J. Linn published a list in 1883 that kept the seven Tejanos added by Pease. The granite "Heroes of the Alamo" monument that was constructed in 1891 and stands on the grounds of the Texas state capitol today kept two of the Tejano names Pease added, subtracted the other five, and added three more, but still left Espalier off. These are only some of the Alamo lists that were published and promulgated. In short, every Alamo defender list published for the first 75 years after the legislature's special act omitted Carlos Espalier.

"A Young Mexican Boy of San Antonio"

The modern view of Carlos Espalier is shaped by the stunningly inaccurate synopsis of Luzgarda Grande's claim file made by Amelia Williams in her 1931 doctoral thesis. This thesis was published, with minor alterations, in segments in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly in 1933 and 1934. Williams's summary is as follows:

But in the archives of the Texas Department of State, Memorial, No. 20, File 25, there are a number of affidavits, made by reputable Mexicans of San Antonio, October 1855, affirming that Charles Despallier and Carlos Espalier were one and the same person. They say, at least, that they had never heard of a Charles Despallier and that they believe these names to be variants of the same name.17

This could not be more wrong. The affidavits presented in October 1855 do not mention Charles Despallier at all. The affidavits presented in July 1856 do mention Despallier, but none of them claim that Despallier and Espalier "were one and the same person" or that the affiants believed them to be variants of the same name. That was Governor Pease's conclusion, not the claims of the "reputable Mexicans of San Antonio." The first four 1856 affiants—how "reputable" they were is unknown— stated that Carlos Espalier was not known as Charles Despallier. The fifth 1856 affiant, Menchaca, stated that there was no such man as Charles Despallier at the Alamo.

Williams continues, "They testify that Carlos Espalier was a young Mexican boy of San Antonio, seventeen years old, and a protege of James Bowie." No, no, no, no, no, and yes. He was a protege of Bowie, but none of the affidavits from either 1855 or 1856 state that Espalier was young, Mexican, a boy, that he was from San Antonio, or that he was seventeen years old. The statements by Ruiz and Navarro affirm that he was "upwards of seventeen" as of the date that Texas declared independence from Mexico. This was what the law for first-class headright grants required. The law did not require claimants to give their age or date of birth; it simply required them to affirm that they were "seventeen and upwards." When affiants were given a testimony to sign, as Ruiz and Navarro were, the testimony simply repeated the required language, without elaboration. It is the same as someone today checking a box to affirm that he or she is at least eighteen to access adult content or to register to vote. There is no way that Williams did not know this. In her research for her thesis, she probably read hundreds of first-class headright claims and the testimonies that were attached to them. She had to have read this phrase, "upwards of seventeen," countless times. For her to interpret it, as she did in only this one case, that the claimant was exactly seventeen is indefensible.

Williams's declaration that the affidavits portray Espalier as a Mexican of San Antonio is not quite as blatantly wrong, but is still wrong, because that is merely her interpretation of some very nebulous statements. Charles Despallier was French-Spanish-American on his father's side and Tejano on his mother's side. He obviously spoke Spanish and was well-known to the Tejanos of Bexar. That makes sense, especially if he was a close companion of James "Santiago" Bowie, who had been married to a Tejana and who lived with his Tejana sisters-in-law. Outwardly, Despallier must have looked more European than Mexican, so that even after hearing him speak Spanish and seeing him circulate among Tejanos with "Uncle" Bowie, Menchaca was slightly taken aback to hear him call Luzgarda Grande, "Mother." The one bit of testimony that might support Williams's interpretation that Espalier was a local is Cayetano Rivas's statement that he knew Carlos Espalier "as well as he did one of his own children." Rivas's statement obviously contains some amount of puffing, but even so, it cannot be entirely disregarded. Then again, Menchaca's statement that Espalier's grandfather resided in Nacogdoches and his other relatives lived in Louisiana is a strong clue that whatever roots Espalier had in San Antonio were shallow. In summary, Williams was wrong to declare that the affidavits portray Carlos Espalier as a Mexican of San Antonio; that is merely the impression she got from them. Her statement that they portray him as seventeen is blatantly wrong. There is nothing in any of the affidavits that exclude Carlos Espalier from being a 20-year-old half-Creole, half Tejano from Louisiana.

After demonstrating such a terrible grasp of what the documents state, it should be no surprise that Williams concludes:

The evidence produced by these Mexicans seems sufficient and conclusive proof that the young Espalier did die at the Alamo, but it is not sufficient to prove that Espalier and Despallier were the same man. In fact, a similarity of name is the only strong point they had for such a conclusion.

Williams's point about the rejection of Espalier being based on "similarity of name" is another figment of her imagination. None of the evidence presented by the Mexicans referred to the similarity of names. Once again, none of the 1855 affiants used the name Despallier at all, four of the 1856 affiants declared that Espalier was not Despallier, and the last one declared that there was no Despallier. The only other person to give any input was Pease, who noted the similarity in names, but did not give it as his reason for finding that they were the same man. No one did. No one has ever based their case for Charles Despallier and Carlos Espalier being the same person only on the similarity of their names.

In 1936, the Alamo cenotaph monument was constructed outside the Alamo. Williams's opinion about Carlos Espalier was literally carved into granite; both Charles Despallier and Carlos Espalier's names are on it. Since then, many researchers, including Walter Lord (A Time to Stand, 1961), Thomas Lloyd Miller (Texana, Spring 1964), and Bill Groneman (Alamo Defenders, 1990), have examined the Alamo defenders list and made their own additions, removals, and changes to Williams's. One constant among them has been keeping Carlos Espalier and Charles Despallier as two different men. Groneman's entry for Espalier in Alamo Defenders reads:

ESPALIER, CARLOS (1819-3/6/1836)

Age: 17 years

Born: San Antonio de Bexar, Texas

Residence: Same

Rank: Private (rifleman)

KIB

Carlos Espalier was said to be a protegé of James Bowie.

His aunt, Doña Guardia de Luz, was his heir. She was granted lands for Espalier's service.

Allegations have been made in the past that Carlos Espalier and Alamo defender Charles Despallier were one and the same. This seems to have arisen merely due to the similarities in their names. No conclusive evidence has ever been put forth to indicate that they were not two distinct people.18

Groneman writes as if the historian's job is to interpret evidence and then place the burden on others to prove his findings to be wrong. That is not how it works. The burden of proof is on the person making the claim to begin with. Williams never offered any proof that Carlos Espalier was a young Mexican boy of San Antonio; she simply claimed, falsely, that was what some documents stated.

Williams's successors' affirmation that Despallier and Espalier were different men does not come from wholesale deference to her, either. Lord and Miller both voiced substantial criticism of her tendency to misrepresent and misinterpret the contents of documents. No one has been more critical of Williams than Thomas Ricks Lindley, who, in Alamo Traces (2003), devotes an entire chapter to how bad her research was, and gives numerous examples of unfounded conclusions she made—but Carlos Espalier is not one of them.

"They Were At Least First Cousins"

One obvious question that Williams, Groneman and the other researchers who assert that Carlos Espalier was a seventeen-year-old Mexican of San Antonio never followed up on is, "who was his father?" This is not a rhetorical or trivial question, either; it is a very real problem for Williams's theory, for a simple reason: Espalier is not a Spanish surname, and there are no records of an Espalier family living in Bexar. The two closest censuses to Carlos Espalier's supposed lifespan of 1819 to 1836 are the 1830 census of San Antonio de Bexar and the 1850 U.S. Census of Bexar County. There are no Espaliers in either of them. For that matter, there are no Espaliers found anywhere in Spanish or Mexican Texas, with one exception: Charles Despallier's father, Bernardo de Espalier.

In 2013, Rasmus Dahlqvist published his biography of the family of Bernard Martin Despallier, named From Martin to Despallier. Using information obtained from archives in Bexar County, Nacogdoches County, Natchitoches, and elsewhere, Dahlqvist presents the following key findings that were not necessarily available to the Texas legislature in 1856 or to Amelia Williams in 1931:

- Charles Despallier's father, Bernard Martin Despallier, married Maria Candida Grande in Nacogdoches in 1806.

- Maria Candida Grande and Maria Luzgarda Grande were the daughters of Luis Grande and Trinidad Sanchez.

- Spanish speakers commonly referred to Bernard Despallier as Bernardo de Espalier or Bernardo Espalier.

- Bernard Despallier and his family lived in Rapides Parish.

- In addition to being Texas revolutionaries, the Despalliers were closely associated with Bowie.19

The above findings should have constituted the "conclusive evidence" that Williams and Groneman claimed was lacking to prove Despallier and Espalier were the same man. Their names did not just happen to sound similar, they were the English version and the Spanish version of the same name, exactly as Governor Pease had stated. Also, there was now documented proof that Carlos Espalier and Charles Despallier had the same maternal grandfather and the same aunt. No objective researcher, starting fresh, would conclude that these were two different men. The problem was that Dahlqvist was not starting fresh; he was working on top of eighty years of the same incorrect conclusion being repeated and defended by one researcher after another. He finds a way to reconcile his findings that does not require overturning eighty years of consensus: "They were at least first cousins."20 He then repeats the longstanding paradigm that the affidavits in the Carlos Espalier file depict him as a seventeen-year-old Mexican boy from San Antonio and that the proof is insufficient that he and Despallier were the same person. On the succeeding pages, he presents information about Maria Candida and Luzgarda Grande's family, which lacks any mention of a third sister—a requirement for Carlos and Charles to be cousins.

Dahlqvist does not explain why he is so bent on preserving the notion that Espalier and Despallier were two different men when his own research leaves no room for that conclusion. Reading the book, From Martin to Despallier in its entirety, however, makes one thing very obvious: Alamo history was not Dahlqvist's element. In the first two thirds of his book, where he lays out history of the Despallier family going back to Bernard's grandfather, Dahlqvist's excellent research skills are apparent. Every fact or piece of information he provides is backed up by one, or sometimes multiple documents, and his conclusions are sound in every instance. Once the calendar year turns over to 1836, though, his methodology and presentation change completely. Instead of presenting and commenting on documents, he merely repeats the assertions of historians such as Williams and Groneman. This is understandable. His family genealogy project, in which he was the first primary researcher, took a turn into the Alamo, the most famous event in Texas history, and a topic that historians had been writing about for nearly 200 years. Few people in his position would have had the boldness to declare that the last eighty years of scholarship in a topic where he had no credentials were wrong. Thus, "they were at least first cousins."

Despallier and Espalier were not first cousins, of course. Not only did Dahlqvist find no evidence that there was a third Grande sister, but his research makes the problem of Carlos Espalier's father even more difficult to answer. In 1819, when Carlos Espalier was supposedly born, the only Espalier or Despallier males known to history living in either Texas or Louisiana were Bernard, 45, and his sons, whose ages ranged from 9 to 3. This means that not only would there have to be an unknown Grande sister, but Carlos Espalier's father was either Bernard himself (making Carlos and Charles both cousins and half-brothers) or an unknown son. Or, possibly, both of Carlos's parents died and Bernard and Maria Candida adopted him, which would make Charles and him not just first cousins, but also adoptive brothers. The mental and logical gymnastics required to keep Carlos and Charles as separate men become ridiculous.

A Summary of the Evidence

The key points in the evidence presented above regarding Carlos Espalier and Charles Despallier are:

- Charles Despallier's father, Bernard Martin Despallier, was a French-Spanish-American whose spent some years in east Spanish Texas, where he was known as Bernardo de Espalier or Bernardo Espalier.

- Bernard Despallier/Bernardo Espalier married Maria Candida Grande, a daughter of Louis Grande of Nacogdoches. They had a son, Charles Despallier.

- Louis Grande had another daughter, Maria Luzgarda Grande. She was Charles's aunt.

- The Despallier clan lived in Rapides Parish, Louisiana. They were associates of James Bowie.

- There were no other known Despalliers or Espaliers in Spanish Texas or Louisiana.

- A document in Charles Despallier's land claim file dated July 1854 has the name Carlos Espalier written on it. Carlos Espalier is the Spanish form of Charles Despallier's name.

- Charles Despallier was in Bexar in January 1836. He was twenty years old.

- Luz Guarda Grande of San Antonio, the daughter of Luis Grande of Nacogdoches, had a nephew, Carlos Espalier. His relatives lived in Louisiana, possibly in Rapides Parish.

- Carlos Espalier was in Bexar in January 1836. He met a legal criteria of being "upwards of seventeen" years old on March 2. He was a companion or aid of Bowie, who he called "Uncle."

Any objective reading of the evidence would lead to the conclusion that Charles Despallier and Carlos Espalier were the same person. While there are some conceivable scenarios that begin with either adoption or a man having children with two sisters, where two closely-related men with the same name both go to Bexar and ultimately die in the Alamo side-by-side, no reasonable interpreter of the evidence would prefer one of those scenarios to the much simpler answer: they were the same man. The tired old rebuttal that the only thing they have in common is their similar-sounding names was untrue the day Amelia Williams wrote it, and it is even more untrue today, given how much additional evidence has been uncovered.

Conclusion

Charles Despallier, a half Creole, half Tejano from Rapides Parish, Louisiana, came to Texas in late 1835. He signed the Goliad Declaration of Independence on December 20. He then went to Bexar, quite possibly with James Bowie, in January. When the Mexican army arrived at Bexar, Despallier entered the Alamo with the rest of the Texians. During an attack on February 25, he exited the Alamo walls and burned some wooden huts that the Mexicans were using for cover. Colonel Travis praised his actions in a letter he wrote that day. Despallier may have left the Alamo after this battle; if he did, he returned with the Gonzales relief force on March 1. He died in the Alamo battle on March 6. In the 1850s, the state of Texas mistakenly issued land grants to both his mother in Rapides Parish and his aunt in San Antonio. The latter grants were issued in the name of Carlos Espalier, the Spanish pronunciation of his name. Historians in the 20th and 21st centuries have treated Despallier and Espalier as two different men, but they were the same man.

By David Carson

Page last updated: September 20, 2024

1Sadly, he is not the only Alamo defender to be duplicated on most lists. There are also James B. Bonham, aka "Jesse B. Bowman" and William Wells, aka "William Wills."

2Jenkins, vol. 2, doc. 283, James Bowie, letter to James B. Miller, 6/22/1835.

3Allegedly, he was murdered by the Rapides Parish Sheriff, James Madison Wells, who later became governor of Louisiana.

4Davis, p. 431

5Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Despalier, Charles

6Dahlqvist, p. 267.

7The age limitation applied only to single men, not heads of households. As there were only one or two fallen Alamo defenders who were under seventeen, and both of them were single, that distinction is irrelevant for our purposes.

8She is not to be confused with Juana Navarro's sister, Gertrudis Navarro.

9"A Mistake," State Gazette (Austin), 7/26/1856, p. 3.

10Letter from M. G. Anderson to the Texas House Judiciary Committee, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.

11The writer was unable to determine what relation, if any, Cayetano Rivas had with Gertrudes Rivas, one of Grande's 1855 affiants.

12Agustin Berrera sworn statement, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.

13Cayetano Rivas sworn statement, Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.

14See Dahlqvist, pp. 237, 287, 414. Bernard entered Bowie's circle in 1825. Dahlqvist writes that he "must have died around this time."

15Dahlqvist, pp. 311-313, finds her in various censuses that give her calculated age in January 1836 as 36, 44, 45, 47, and 48. Discarding the outlier of 36 and taking the median of the others gives up 46.

16Hansen, doc. 3.2.1, Antonio Menchaca, memoirs, 1937.

17Williams, p. 255

18Groneman, pp. 42-43.

19Dahlqvist, pp. 181, 217, 237, 245, 250-251, 257, 263, 312.

20Dahlqvist, p. 305-313.

- Bennet, Miles S., "The Battle of Gonzales, the 'Lexington' of the Texas Revolution,' Texas Historical Association Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 4, April 1899.

- Brown, John Henry, History of Texas From 1685 to 1892, vol. 1, L. E. Daniell, 1892.

- Davis, William C., Three Roads to the Alamo, HarperPerennial, 1998.

- De Shields, James T., Border Wars of Texas, The Herald Company, 1912.

- Dahlqvist, Rasmus, From Martin to Despallier: The Story of a French Colonial Family, self-published, 2013.

- Gammel, H. P. N., The Laws of Texas, 1822-1897, The Gammel Book Company, 1898.

- Groneman, Bill, Alamo Defenders, Eakin Press, 1990.

- Hansen, Todd (ed.), The Alamo Reader, Stackpole Books, 2003.

- Jenkins, John H. (ed.), Papers of the Texas Revolution, Presidial Press, 1973.

- Pease, Elisha M., "Muster Roll of the Alamo," Galveston Daily News, July 19, 1876.

- Williams, Amelia, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and the Personnel of its Defenders," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, April 1934.

- Texas General Land Office, "Categories of Land Grants in Texas," January 2015.

- Republic claims file 13765.

- Republic claims file 50815.

- Nacogdoches First-class 825, Charles Despallier Decd.

- Fannin Bounty 721, Charles Despallier.

- Nacogdoches Donation 347, Chaz Despallier.

- Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Despalier, Charles, 7/27/1856.

- Memorials and Petitions, 1834-1929, Espalier, Charles – Heirs of, July 1856.

- Bexar County marriage registers, vol. C, p. 202.

- "A Mistake," State Gazette (Austin), 7/26/1856, p. 3.

- Bexar First-class 1348, Carlos Espalier.

- Bexar Bounty 1337, Carlos Espalier.

- Bexar Donation 1271, Carlos Espalier.