The Narváez Expedition in Matagorda County

The Narváez Expedition in Matagorda County

Introduction

This article identifies the presence of survivors of the Narváez Expedition in Matagorda County.

Five parties of the Narváez Expedition, including some 97 survivors, passed through Matagorda County at some point between 1528 and 1533. As best as can be determined, all of them followed the same route: northeast to southwest along the coast of the long Matagorda Peninsula. Only two deaths from the expedition were recorded in Matagorda County. One man may have returned here to live after the rest of the survivors moved on.

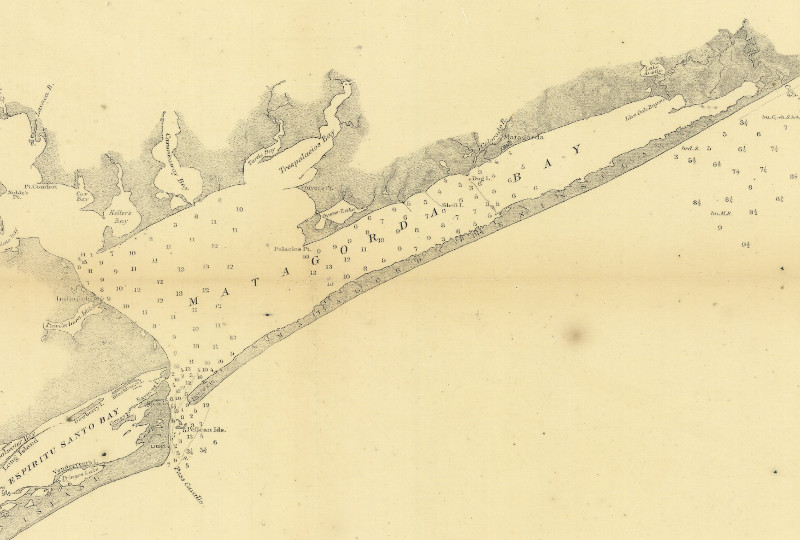

Map of the Coast of Matagorda County

[-]Collapse Map [+]Expand MapCaney Creek

The first stream in Matagorda County that the Narváez Expedition survivors would have encountered is Caney Creek. Like Oyster Creek and the San Bernard River, Caney Creek discharged directly into the Gulf of Mexico before the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway was built, but now it discharges into the waterway instead. Its mouth used to be about 12 miles, or 3½ leagues, from the mouth of the San Bernard River.

Order your copy of Children of the Sun: Following in the Footsteps of Narváez and Cabeza de Vaca, by David Carson of TexasCounties.net, available in E-book and paperback formats.

Geography

Both records of the Narváez Expedition - Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca's La Relación and the Joint Report, which was based on the testimony of Cabeza de Vaca and two other survivors - state that two of the parties of survivors crossed four rivers before coming to a large bay. As explained in the previous article, "The Narváez Expedition in Brazoria County," The texts give enough information to allow us to conclude that the second river was the Brazos. With that being the case, the third river had to have been the San Bernard. The Joint Report states, "they continued another five or six leagues to another great river."1 Many Cabeza de Vaca route interpreters believe that Caney Creek was the fourth river. Brownie Ponton and Bates McFarland found this river to be Caney Creek in their pivotal 1898 study. Harbert Davenport and James B. Wells agreed, as did Alex D. Krieger. So have most others. The only two problems with this interpretation is that Caney Creek is neither five or six leagues from the San Bernard, nor is it a great river.

Let us first look at the problem of distance. Past Caney Creek, the Texas coast turns into a series of long, thin peninsulas and islands. Historically, there were no rivers or creeks of any kind between Caney Creek and the Rio Grande - only some bays, inlets, and saltwater bayous separating the barrier islands. So, if the expedition survivors followed the coastline, and the Brazos River was their second river and the San Bernard the third, then Caney Creek, as the only stream left on the coast, had to have been the fourth. Some route interpreters, however, have thought that instead of following the coastline, the travelers went inland and followed the north shore of Matagorda Bay. There are quite a few problems with this interpretation, one of them being that it does not solve the problem of the fourth river at all. These theories propose that the fourth river was the Colorado, which, at 33 miles or 9½ leagues from the San Bernard, makes the distance issue worse, not better. There is a stream, Live Oak Bayou, between Caney Creek and the Colorado, about six leagues from the San Bernard, but it is even smaller than Caney Creek. And, even if Live Oak Bayou was the fourth river, then what of the Colorado? Everyone on the expedition would have had to have crossed it, if they were following the shoreline of Matagorda Bay, but both the Joint Report and La Relación state that there were four rivers, not five. The most practical solution to this problem is to conclude that the survivors stayed on the coast, the fourth river was Caney Creek, and the Joint Report got the distance a little wrong.

The question of whether Caney Creek could have been a "great river" has a more satisfactory, and interesting, answer. There is significant geological evidence that Caney Creek was once the original channel of the Colorado River. According to a 1974 report authored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture:

Caney Creek occupies a former course of the Colorado River...Recently, within the past several hundred to several thousand years, the Colorado River has been diverted from its old Caney Creek course to its present course along the south wall of the alluvial valley and in the narrow alluvial belt south of Wharton. The course south of Wharton most likely occupies the much enlarged channel of a minor stream that is headed in the direction of the larger alluvial plain. The diversion may be related to faulting and regional tilting in the Eagle Lake area to the north where Caney Creek originates.

The headwaters of Caney Creek are in Wharton County. The channel - largely dry, but spotted with many small ponds - can be traced on satellite photos and topographic maps to the little town of Glen Flora, about six miles northwest of Wharton. (This location can be viewed on the map in Figure 1 by panning up or zooming out.) It stops about a quarter of a mile short of the Colorado River. Once the Colorado cut through to its new channel, the banks of the old channel would have gradually eroded. Sediment runoff from the drainage area would have collected on the bottom because there would be less water flowing through to push it downstream and out into the Gulf. This process would have taken a long time, however. In the 1800s, vessels weighing up to 150 tons navigated 30 to 40 miles up Caney Creek. During the Civil War, the Confederate Army built fortifications at the mouth of Caney Creek to keep Union ships from entering it. The wreck of a paddlewheel steamboat still lies beneath the waters of Caney Creek a few miles outside of Bay City, 25 miles from the coastline. If Caney Creek was still large enough in the 1800s to be a major shipping artery, one can only imagine how big it would have been in the 1500s.

The Narváez Expedition Survivors

In November 1528, five boats carrying survivors of the Narváez Expedition landed at various placed along the Texas coast. The boat commanded by Comptroller Alonso Enríquez, the third-highest-ranking officer on the expedition, capsized at the mouth of the San Bernard River in Brazoria County. Enríquez and his men left their boat at the river and began walking southwest along the coast, possibly after taking a day or two to recuperate from a week-long ordeal of being lost at sea. They most likely crossed Caney Creek on their first day of walking, which may have been around November 9.

Enríquez and his men did not know it at the time, but they were being followed by two other parties of survivors. Governor Narváez was not far behind, skimming the Gulf coast in his still-seaworthy boat. Using the estimated travel speeds presented in previous articles on this topic, Narváez and his men probably crossed Caney Creek on or around November 11.

The expedition chronicles inform us that two of the other boats had a combined total of about 80 survivors when they landed. Assuming that the survival rate on Enríquez's and Narváez's boats was about the same, then each of their parties had about 40 men in them when they crossed Caney Creek.

The next party from the expedition to cross Caney Creek was a group of four men named Álvaro Fernández, Méndez, Figueroa, and Astudillo. They were from the combined parties of two boats that landed on Follet's Island in Brazoria County. When attempts to repair and relaunch the boats ended in failure, these four men, who were considered the strongest of the castaways, and were also good swimmers, began walking down the coast in hopes of reaching Pánuco in New Spain (near present-day Tampico, Mexico) while the rest of the castaways remained on Follet's Island for the winter. One of the natives of Follet's Island went with them as their guide. Our best estimate of when this party crossed Caney Creek is November 12 - three days behind Enríquez's party and one day behind Narváez.

The texts do not describe any of these three parties' journeys in this area, but one must wonder whether Narvaez's men or the small group walking from Follet's Island saw trails, campfires, or other signs left by Enríquez's group as they followed in their footsteps.

On April 1, 1529, with winter past and no rescue ship in sight, Andrés Dorantes gathered together all of the Europeans who survived the winter on and around Follet's Island and who were able to walk and led them on a march toward Pánuco. There were eleven men in this party by the time they reached Matagorda County and Caney Creek. This was probably on the fourth day of their journey, or April 4. They had seen Enríquez's boat on the San Bernard River and had, no doubt, been looking for signs of the people from it while walking down the coast, but by then, the trail was five months old, so they may not have found any.

The Joint Report states that when this group reached Caney Creek, they encountered some natives on both sides of it. This is the first mention of natives on the Texas coast by any of the expedition parties since leaving Follet's Island. The natives on the east bank ran from them. Those on the west side crossed over to meet them. They had seen both Enríquez's and Narváez's parties pass through five months earlier. They took the Europeans across the river and gave them some food. The travelers spent the night there. The Joint Report does not mention the names of any of the native tribes that the survivors encountered, but based on information given in La Relación, these natives were most likely the ones Cabeza de Vaca called Deaguanes.

The expedition chronicles state that Cabeza de Vaca was too ill to join Dorantes's party, but that after that group left, he recovered. He then did a lot of traveling for the next four years. His travels supposedly took him as far as Matagorda Bay then back to Galveston Bay, twice. In the spring of 1533, he picked up Lope de Oviedo, another man who had been too ill to join Dorantes's party, and they left Follet's Island together. If so, then when these two men crossed Caney Creek in 1533, it would have been Cabeza de Vaca's third time to cross it and Oviedo's first.

Modern History

The first settlers came into the Caney Creek area in the early 1830s as part of Stephen F. Austin's colony. George Sargent, an Englishman, purchased some bottomland on the east bank of the creek near the Gulf coast in 1834 and built a house there. The area around his homestead has been settled continuously up to the present, but hurricane after hurricane deterred the community's growth for decades. Sargent himself died in a hurricane in 1875. In 1925, the town of Sargent had a population of 23. By 1940, it had 80 residents, a school, and a few businesses. In the second half of the 20th century, Sargent grew into a fishing and leisure community. As of 2000, it had a few hundred residents, two churches, some stores, and a motel.

Order your copy of The Account of Cabeza de Vaca: A Literal Translation with Analysis and Commentary, translated by David Carson of TexasCounties.net, available in E-book and paperback formats.

Matagorda Peninsula

The Matagorda Peninsula, which shelters Matagorda Bay from the Gulf of Mexico, makes up most of the southern boundary of Matagorda County. It begins just west of Caney Creek and extends southwest for 51 miles. It is about 1 mile wide.

Today, this "peninsula" is technically a chain of islets, not one solid landmass. An opening at the east end of Matagorda Bay called Mitchell's Cut separates the peninsula from the mainland, but this cut is shallow and has had to be dredged to keep it open, so it may have closed and reopened more than once over the centuries. The main natural entrance to Matagorda Bay is Cavallo Pass, at the west end of the peninsula. A manmade ship channel has been cut about 4 miles east of there. Another manmade channel is at the Colorado River. Other small, natural cuts exist in places where the peninsula is narrow. These cuts have no doubt been closed at other times, and other small cuts no doubt once existed in other places where they are now closed. Figure 4, above, is a map of Matagorda Bay and Matagorda Peninsula from 1867. For reasons which will be explained in this section, it is a better representation of this area at the time of the Narváez Expedition than recent maps or satellite photos would be.

The channel of the Colorado River that cuts across the peninsula about halfway down its length, seen on the Google map in Figure 1 at the top of this page, is a recent development. Historically, the Colorado River emptied into Matagorda Bay at the present-day town of Matagorda, as indicated on Figure 4. In 1690, Alonso de León, the first Spanish explorer to see the Colorado River, described an enormous "raft" of logs, trees, and brush that had accumulated in the river, preventing navigation further than about a dozen miles upstream. The raft was still there when settlers arrived in the early 1800s. It spread out over a distance of five miles between Bay City and Wharton, and was estimated to be growing at the rate of 500 feet per year. Not only did it impede navigation, but it also caused flooding. State and local authorities formed several commissions and plans to deal with the raft every few years, but nothing effective was ever done. In order to carry goods from Columbus and La Grange down to the port at Matagorda, teams had to unload vessels upstream of the raft, haul the cargo around it, and load it on vessels downriver. In the 1850s, a canal was dug to bypass the raft, and ships did successfully navigate the Colorado for the first time, but the canal quickly filled up with new material. In 1925, engineers began digging a channel through the raft, rather than around it. This project was completed in 1928, by which time the raft was fourteen miles long. The following year, a huge flood came and flushed the entire raft into Matagorda Bay. Within a few years, the town of Matagorda, once a major Texas seaport, was completely landlocked. By 1935, the Colorado River delta reached all the way across Matagorda Bay, dividing it into East Matagorda Bay and West Matagorda Bay. A channel was cut that year to allow the river to empty into the Gulf. In 1990, a second channel was cut to divert the river into West Matagorda Bay. The Gulf channel still exists, but it has been engineered so as not to carry any of the flow from the river, making it a saltwater pass.

Somewhere between the San Bernard River and Cavallo Pass, Governor Narváez and his group caught up with Comptroller Enríquez and his group. According to Cabeza de Vaca, Narváez and his boat continued sailing past Enríquez's party. After he crossed a wide inlet, Narváez dropped his people off and came back to collect Enríquez's party, taking them across the pass next. If this is what happened, then the place where the two groups met would have been somewhere between the fourth river and the wide inlet; i.e. between Caney Creek and Cavallo Pass. The fact that Narváez, in his boat, happened to find Enríquez's group walking on land supports the theory that they were walking down the Matagorda Peninsula, not along the north shore of Matagorda Bay.

The Joint Report describes the meeting between Narváez's party and Enríquez's party differently. It states that Narváez put his people ashore with Enríquez's "so they all could be together on the coast" and because "they were weary of the sea, and they were not carrying anything to eat." Narváez also wanted to make his boat lighter, which hints that it may have been wearing out or in need of repair. He remained in the boat and took it down the coast, in view of the party on land, "in case there was a bay or river to cross."2 When they reached a large bay, Narváez took everyone across in the boat. Even though the Joint Report describes the encounter differently, neither it nor La Relación mention his boat ferrying the combined groups across more than one body of water, so Enríquez must have been past Caney Creek and on the Matagorda Peninsula when Narváez found him. In all likelihood, they were not that far from Cavallo Pass. Neither of the texts mention Narváez camping or spending the night after meeting Enríquez until all of the men had crossed the pass, leaving the impression that they met and crossed the pass together on the same day. If this impression is correct, this encounter probably happened around November 12.

The four strong European swimmers and one native walking from Follet's Island would have been able to travel faster than Enríquez's group of forty. They could have been two days behind Enríquez's party by the time they reached the end of the peninsula and were probably well aware that there was a group walking ahead of them.

The Joint Report states that Dorantes's party camped on the west bank of the fourth river, or Caney Creek, then continued their journey the next day. This is the first mention of any passage of time in the description of Dorantes's journey down the coast, but Caney Creek is 37 miles from the start of the journey - a distance that is impossible to cover on foot in one day, especially considering the four substantial rivers they had to cross, two of which involved making rafts on site. The group reached the other end of the Matagorda Peninsula "on the fourth day." This has to be the fourth day after crossing Caney Creek, not the fourth day after leaving Follet's Island. This means that the group traveled down a 50-mile stretch of level land, with no large streams or other obstructions, at an average rate of between 12½ and 17 miles per day. If their journey from Follet's Island began on April 1, 1529, they probably camped at Caney Creek on the night of April 4. They began walking down the Matagorda Peninsula on April 5 and reached the end of it on April 8. Sometime during this leg of the journey, two people died "from hunger and fatigue."3 We do not know exactly who they were, but their names were among this list of six: Estrada, Tostado, Chaves, Gutiérrez, Benítez, and Francisco de León.

Dorantes's party's only means of getting across the inlet was a damaged canoe they found. The Joint Report does not say whether all nine of them could fit in the canoe, or whether they had to make multiple trips across the pass; it says only that they were at the pass for two days.

Cabeza de Vaca and Lope De Oviedo traveled down the Matagorda Peninsula in the spring of 1533 as they made their way down the coast from Follet's Island. Cabeza de Vaca wrote that one night when he was staying with the Deaguanes, they were attacked by the neighboring Quevenes, and three of the Deaguanes were killed. The Deaguanes launched a retaliatory attack later the same night, killing five Quevenes. He did not state whether this occurred in 1533, when Oviedo was with him, or in one of his two earlier visits to the area. He also did not specifically state where it occurred, but Matagorda Bay was the Deaguanes' territory, while the Quevenes lived across Cavallo Pass.

We do know that the Deaguanes took Cabeza de Vaca and Lope de Oviedo across Cavallo Pass in 1533. Perhaps the two Spaniards encountered them on the Matagorda Peninsula, or perhaps they found them further east, such as at Caney Creek. If the latter, the natives more than likely gave the Spaniards a ride in their canoes all the way down the north side of the peninsula.

The first settler on the Matagorda Peninsula was Thomas DeCrow, who built a farm on the western tip, which was called Decros Point. Samuel A. Maverick and his wife came in 1844 and raised cattle there. In the 1840s and 1850s, there was a town with a post office and schools. The settlement was vacated during the Civil War. It was then obliterated by a hurricane in 1875 and was never rebuilt. Because of several factors which are explained in the next article, Cavallo Pass began to fill in with sand in the 20th century. A sandy beach about 1.5 miles long now extends into the pass beyond Decros Point.

The U.S. Army operated an airfield on the Matagorda Peninsula during World War II, but otherwise, it has been mostly uninhabited in recent times. It has no roads and can only be accessed by air or water.

Summary

| County | Castaways Who Visited | Dates | Castaways Who Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matagorda | Five parties including about 97 people | From about Nov. 9 to Nov. 15, 1528, April 4 to April 10, 1529, and spring of 1533 | Two members of Dorantes's party - of "hunger and fatigue" on the Matagorda Peninsula |

By David Carson

Page last updated: March 27, 2017

1Joint Report, Chapter 3

2Joint Report, Chapter 3

3Joint Report, Chapter 3

- Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar Núñez - La Relación. Translated to English by David Carson, 2016

- "The Joint Report Recorded by Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes," translated to English by Gerald Theisen, published in The Narrative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca by The Imprint Society, 1972

- Clay, Comer - "The Colorado River Raft", published in The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 52, 1949

- Hedrick, David, "The Investigation of the Caney Creek Shipwreck Archeological Site 41MG32" (master's thesis), 1998

- Krieger, Alex D. - We Came Naked and Barefoot, University of Texas Press

- Texas State Historical Association - The Handbook of Texas Online

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service - "Soil Survey of Wharton County, Texas," 1974