David Wilson

Introduction

David Wilson is not one of the Alamo defenders who historians tell stories about. He did not play bagpipes while David Crockett fiddled, he was not the first Texian soldier to cross Colonel Travis's line in the sand, he did not rouse the rest of the garrison out of bed the morning of the Mexicans' attack, and he was not killed while attempting to blow up the gunpowder storeroom. While he may have done thousands of interesting things during his life, including during the 13-day siege of the Alamo and the battle that took place on March 6, 1836, no one made any record of any of them that has survived. All we know is that he fought and died for Texas on that fateful day. A true, accurate, biography of Alamo defender David Wilson is, perhaps unfairly, sparse:

David Wilson

David Wilson arrived in Nacogdoches on or before May 2, 1835. Nothing is known of his parents, his birth, or his origin. If he had a wife or family, he did not bring them with him to Texas.

Wilson was in debt when he left Nacogdoches to join the Texas Revolution. He was in Bexar as of February 1, 1836 and voted in the Texian garrison's election that day for delegates to the upcoming General Convention on Washington-on-the-Brazos. He entered the Alamo on February 23 and died in the battle on March 6.

The above biography of David Wilson is accurate, but it is not the biography one will find in any book, article, or web site. Those all tell a different story—a story that is almost entirely false. These falsehoods are not ordinary mistakes, either; some are lies that were told deliberately. A person who was uninterested in history, motivated entirely by greed, told bald-faced lies for the purpose of committing fraud. They knew what they were doing, and they had help. Their lies became the foundation of David Wilson's biography.

The perpetrators of the David Wilson fraud ended up getting thousands of acres of public land that they were not entitled to. This land was unclaimed, and would have remained unclaimed had they not acted, so no particular private party lost out because of them. Their victims were the government of Texas and the public it serves and represents. Due to the passage of time and the number of times the land has changed hands since then, restitution is irrelevant. The statute of limitations expired long ago, and no remedy is possible. The David Wilson fraud is no longer a matter of any legal importance. It should still matter to Alamo historians, though, because the false information inserted into his biography by these fraudsters is still there. The opportunity to honor David Wilson's sacrifice at the Alamo by awarding land to his estate is long gone. The least we can do is strip away the misinformation and give an accurate biography of him. That is what this article intends to do.

David L. Wilson, Age 29, From Scotland

The Alamo's official web site is www.thealamo.org. This is where the public goes to learn who the men who died at the Alamo were. Yes, their names have been carved on monuments of bronze, granite, and marble—as well they should—but there are two drawbacks to using monuments as an official Alamo defender list. First, one must go look at the monument to see it, or rely on photographs. Second, mistakes are difficult to fix. A web site, on the other hand, is easy to change and can be seen by anyone in the world on a device at his or her fingertips. Therefore, if there is any one place one ought to expect to find accurate, up-to-date information on the Alamo heroes, thealamo.org is it. Here is how David Wilson's bio currently reads on thealamo.org:

Wilson, David L.

Age: 29

Rank: Garrison Member

From: Scotland

David L. Wilson, Alamo defender, son of James and Susanna (Wesley) Wilson, was born in Scotland in 1807. In Texas he lived in Nacogdoches with his wife, Ophelia. Wilson was probably one of the volunteers who accompanied Capt. Philip Dimmitt to Bexar and the Alamo in the early months of 1836. He remained at the Alamo after Dimmitt left on the first day of the siege. Wilson died in the battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836.1

In the corner of this brief biography on the Alamo's web site is the image of a Scottish flag. Spend much time researching Wilson on the internet, and you will find that groups that celebrate Scottish heritage and culture proudly claim David Wilson as one of theirs.

Unfortunately, this biography has more mistakes in it than it has accurate facts. Wilson's age and year of birth are unknown. If he had a middle initial, he did not use it, and we do not know what it was. We do not know where he was from, but there is no evidence that he was born overseas. James and Susanna Wilson were not his parents. It is correct that he lived in Nacogdoches, but he was unmarried. There is no record of Ophelia Wilson, who was unrelated to him, ever being in Nacogdoches. The notion that he went to Bexar with Philip Dimittt2 is highly speculative and probably incorrect. Wilson did die in the Battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836.

The next place many researchers would go to find information about Alamo defenders is The Handbook of Texas, by the Texas State Historical Association. This resource contains tens of thousands of articles on Texas history written by professors, published authors, and other experts. In the past, the Handbook was a print resource, and it is still available that way (as a very large, heavy volume, larger than its name would imply), but it is also online at the association's web site, tshaonline.org. Here is how Wilson's entry reads there:

By: Bill Groneman

Published: September 1, 1995

Wilson, David L. (1807-1836). David L. Wilson, Alamo defender, son of James and Susanna (Wesley) Wilson, was born in Scotland in 1807. In Texas he lived in Nacogdoches with his wife, Ophelia. Wilson was probably one of the volunteers who accompanied Capt. Philip Dimmitt to Bexar and the Alamo in the early months of 1836. He remained at the Alamo after Dimmitt left on the first day of the siege. Wilson died in the battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836.3

Now we know where The Alamo got its biography for David L. Wilson; it used the Handbook of Texas's entry for Wilson word-for-word, letter-for-letter. That is not necessarily a bad thing; in fact, it makes perfect sense that the curators of the Alamo web site would use the Handbook in this way. After all, what better authority is there?

The Handbook's entry on David Wilson was written by Bill Groneman. The author of several books on the Alamo, Groneman's most important work is Alamo Defenders, which he produced in 1990. This book contains biographies on everyone Groneman believed died at the Alamo, plus some messengers who were sent out during the siege, women and children who survived the battle, and other people who were thought to have been in the Alamo at some point during the siege. Of the countless number of books written about the Alamo, Alamo Defenders remains, to this day, the most oft-cited book in publication on the topic of Alamo biographies. Groneman's entry on David Wilson, found on page 121 of Alamo Defenders, reads:

WILSON, DAVID L. (1807-3/6/1836)

Age: 29 years

Born: Scotland

Residence: Nacogdoches, Texas

Rank: Private (rifleman, possibly Captain Dimitt's company)

KIB

David L. Wilson was the son of James and Susanna Wesley Wilson. His wife, Ophelia, was the administrator of his estate. Ophelia later married Albert Henning.

David may have been one of the volunteers who accompanied Philip Dimitt to Bexar and the Alamo.4

This is substantially the same as Groneman's biography for Wilson in the Handbook of Texas. There are two differences: the omission of Ophelia's remarriage, and Groneman's change from his original wording, "may have been one of the volunteers..." to "was probably one of the volunteers..." for the Handbook. This change between "may have been" to "was probably" is subtle, but important. Very little in history can be proven beyond any doubt. Even when historians write about events without giving any qualifiers or indicators of uncertainty, there usually is some. For example, there is no ironclad proof that David Wilson was from Nacogdoches, but there is good evidence that he was, and no evidence that he was not. Any reasonable examiner of the evidence would conclude that he was from Nacogdoches with no worry about being contradicted by another examiner of the evidence. That is why we can write things like, "David Wilson was from Nacogdoches," without any qualifiers, even when we cannot prove it. When a historian does use a qualifier like "probably," then, it means there is real doubt. It is that historian's opinion or conclusion that something probably happened, but other historians looking at the same evidence might disagree. When a historian uses a qualifier like "possibly" or "may have," though, that shows a severe drop in his or her confidence level. It generally means that there is enough evidence to justify proposing that there was a connection between two things, but not enough to make any sort of reasonable conclusion. Groneman's original belief that Wilson "may have" gone to Bexar with Dimitt is technically feasible—many things "may have" happened—but he did not, by any reasonable standard of interpretation, "probably" go to Bexar with Dimitt. This will be discussed again later in this article.

We see above that the biography for David Wilson that Groneman published in 1990 is still used today by the internet's two leading authorities on the topic of Alamo defenders. It is also the biography used by virtually everyone else. At the time this article was posted, a scan of search engine results for "david wilson alamo" returned page after page of Groneman's biography of David Wilson—many on sites devoted to Scottish or Celtic topics—with no other view or commentary offered. A biography written by one historian over thirty years ago has become not just the leading interpretation of the evidence, but is the only interpretation available, even though the only things it states accurately are "lived in Nacogdoches" and "died at the Alamo."

David Wilson, Private, Nacogdoches

The reason that we know, or have a basis to conclude, that a man named David Wilson died at the Alamo is because his name appears on three early Alamo casualty lists. (For an explanation of when these casualty lists were made, by whom, and of their importance in Alamo personnel research, see our article, "Alamo Personnel - Contemporary Casualty Lists.") On all three lists, his name is written as David Wilson, and all three lists indicate that he was from Nacogdoches. All three lists indicate that he was a private, either by putting the word "private" next to his name or including him in a group of soldiers under the heading, "Privates." Given that these casualty lists lack first names and origins for many Alamo defenders, and that some of the information they give about the same man often varies from one list to the next, the uniformity of the three lists in identifying this man as "David Wilson, Private, Nacogdoches" gives us a level of confidence about him that we often lack for other Alamo defenders.

There is another contemporary document that supports the casualty lists' assertion that a David Wilson died at the Alamo. On February 1, 1836, the Texian soldiers in Bexar held an election for delegates to the upcoming General Convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos. It was not a secret ballot; each man's vote was recorded. The 82nd name on the voting roll reads, "D. Wilson." From this, we know that there was a Texian soldier named D. Wilson in Bexar three weeks before the Alamo siege began. That does not prove that he was still in Bexar three weeks later, but between this voting roll and the three casualty lists, we have good reason to believe, and no reason to doubt, that a man named David Wilson died in the Battle of the Alamo, that he was a private, and that he was from Nacogdoches.

The first appearance of the name David Wilson in any Texas document is in a certificate of character presented in Nacogdoches on August 9, 1835. This document is filed in the Texas General Land Office as Character Certificate SC 70:63. It is written in Spanish and reads as follows:

El ciud. Radford Berry, alcadle unico constitucional de esta municipalidad.

Certifico que el Estranyero David Wilson es un hombre de muy buena moralidad y costumbres, amante a la constitucion y leyes del pais y de la religion cristiana de estado casado con familia; todo lo espresado arriba ha sido probado por un testigo y a pedimento verbal de la parte de doy la [illegible] en la villa de Nacogdoches a dia 9th Aug[illegible] de 1835

Radford Berry

[rubric]

Translated to English, this reads:

The citizen Radford Berry, the only constitutional alcadle of this municipality.

I certify that the Foreigner David Wilson is a man of very good morals and customs, lover of the constitution and laws of the country and of the christian religion of status married with family; everything expressed above has been confirmed by a witness and a verbal motion on the part of I give the [illegible] in the town of Nacogdoches on the 9th day of August 1835

Radford Berry

[rubric]

At first glance, this document appears to tell us that David Wilson arrived in Nacogdoches on or before August 9, 1835 and that he was a family man. But there are several reasons why we ought to take a second or third glance at this document. Most striking is the clumsy way that the phrase "of status married with family" is worked in. Radford Berry's Spanish was imperfect, to be sure, but this phrase is just sort of jammed into the middle of an otherwise fundamentally sound sentence, without any regard for grammar or syntax. Was Berry stating that Wilson was married and had a family, or was the phrase there for some other, poorly expressed, reason? Furthermore, it is unusually vague for a document such as this. Most documents of this type would say something like "brings with him one woman and one child, three persons total," not "of status married with family." Many men did not bring their families with them to Texas; quite often, a man would come to Texas alone, or with another man, such as a brother or friend, get settled, and then bring or send for their families to come join them. In such cases, they were only able to claim a single-man's colonist grant at first, then they could apply for an augmentation after their families arrived. Did David Wilson have his family with him, in Nacogdoches, on that date? It was necessary to know this when issuing a colonist grant. There is no way to tell for sure, but our instincts as researchers tell us he did not, or the document would have more clearly said he brought his family with him, and how many persons there were in total.

The above document does not say where David Wilson immigrated from, or when. This is not necessarily a red flag about the document itself, for sometimes this information was not given in a character certificate. What is more problematic is that there is no record of a land grant being associated with it. Men did not submit certificates of character for no reason; they did it to get a colonist grant. Why did Wilson not get one? Was he denied? Was his application held up? Was it over confusion about what "of status married with family" meant? Did he fail to take some other required next step? We can only speculate.

The above document shows us that there was a David Wilson in Nacogdoches in 1835 who was at least interested in getting a colonist grant. He may or may not have had a family. If he did, it did not appear to have been with him. As for whether this man was the Alamo defender, we must set this document to the side for now and move on to the next one.

One of the first acts taken by the new Republic of Texas was to grant land to its citizens. Every white or Hispanic man who immigrated before Texas' declaration of independence on March 2, 1836 and who had not already received a colonist grant was entitled to a "first-class headright" grant.5 Single men who were at least 17 years old were entitled to third of a league of land, while heads of household were entitled to one league and one labor. Additionally, all soldiers who served in the Texas Revolution were entitled to "bounty" grants. These grants varied in size according to the soldier's term of service, but soldiers who died in battle were usually given the maximum-size grant. Participants in certain battles or engagements designated by the Republic Congress were further entitled to "donation" grants. If the grantee was dead, his heirs were entitled to the grants. Every soldier who died at the Alamo was entitled to a bounty grant and a donation grant, and those who had not previously received a colonist grant were also entitled to a first-class headright grant. The process of applying for these grants and having them approved generated a lot of paperwork. This grant-related documentation is the best resource there is for learning about most of the men who died at the Alamo, including David Wilson. Everything we know about Private David Wilson of Nacogdoches, except for the casualty lists and voting roll mentioned above, is from land grant documentation.

The process for obtaining a headright grant in the Republic of Texas began with the potential grantee, or his heirs or administrators in the case of a deceased person, to apply to a local board of land commissioners. The applicant stated why they were entitled to a grant, and they brought witnesses to testify to whatever facts they knew. If the board decided that the applicant met the requirements of the law, it issued a certificate that approved him to have a survey made of a certain size. It was then up to the applicant to continue the process by getting the survey made and making the other required filings with the General Land Office, which actually issued the grant.

In the archives of early Nacogdoches County, there is a motion filed on January 31, 1838 in the local probate court wherein George Pollitt, through his attorney, requested to be appointed the administrator of the estate of the late David Wilson. According to Pollitt, Wilson "departed this life on or about" March 6, 1836. He died intestate, that is, without a will. He possessed little to no property, but left debts to certain people, including Pollitt. Pollitt stated that Wilson was entitled to land as a citizen of Texas and to other compensation for his service in the Texas army. Because no other persons had come forward to claim administration of David Wilson's estate, he requested that appointment.6

Pollitt's claims that the late David Wilson served in the Texas army and died on or about March 6, 1836 allude to him dying at the Alamo. Pollitt's statement that Wilson did not leave a will and that no one else had filed for administration of his estate implies that he had no known heirs in Texas.

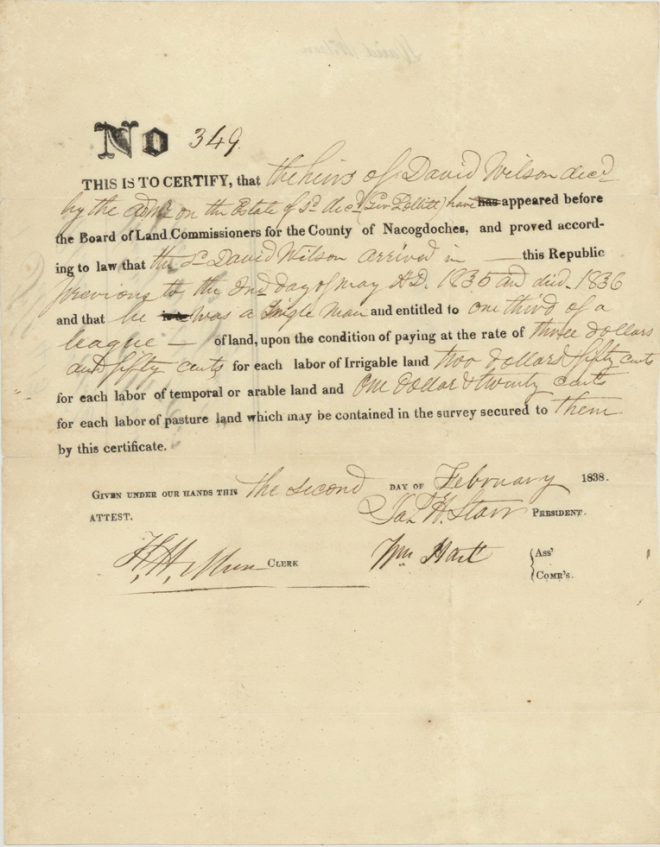

Pollitt's request to be appointed David Wilson's administrator was granted. He then presented his application for Wilson's first-class headright grant to the Nacogdoches County Board of Land Commissioners. He brought three witnesses. The record gives their names and the secretary's brief synopsis of their testimonies, not the testimonies themselves. The secretary wrote that the first witness, William R. Luce, said he "Knew him before the 2d May 1835, lived in this county,went to the Army, knew him on his way to the Army." The testimony of the second witness, David Cook, was not recorded at all. The third witness, Lewis Rose, testified that he "Knew him before the 2nd May 1835, was in the Alamo when taken." May 2, 1835 was a standard date used by the Nacogdoches County Board of Land Commissioners when considering headright claims, and thus has no particular significance to David Wilson's biography. In other words, we should not assume he did anything special or relevant on that date. These testimonies are sufficient to show that Wilson qualified for a first-class headright grant.7 The board agreed and issued a certificate entitling Pollitt to receive a single-man's grant of one third of a league.8 Pollitt had a survey made in Robertson County. The grant, filed as Robertson 1st-Class 413, was patented, or issued to the new owner, in 1848. It was common for approved land grants to take years to become patented, which is why grantees frequently sold the unpatented grants for cash, especially if they did not have any desire for the land itself. Pollitt's last documented involvement with the grant was in 1840; he may well have sold his certificate and survey to pay off his claims against Wilson's estate, as well as the claims of any other creditors. No actual heirs of Wilson's were ever identified.

Taken together, the Bexar garrison voting roll, the three casualty lists, and the above headright grant constitute strong evidence that a Private David Wilson of Nacogdoches died at the Alamo. He was in Nacogdoches on or before May 2, 1835. He was apparently either single or had a family outside of Texas who had no contact with his estate or his administrator after his death. He may have been the same David Wilson who presented a certificate of character in Nacogdoches in August 1835.

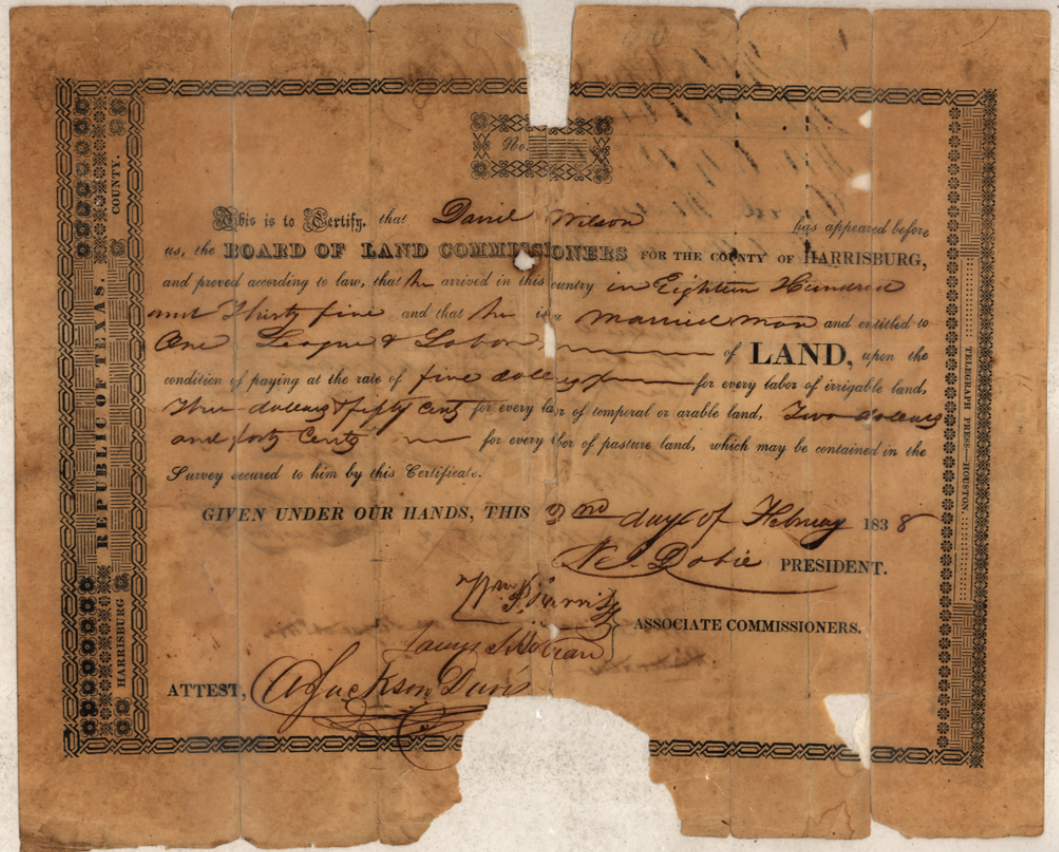

David and Ophelia Wilson of Houston

On the same day that George Pollitt was in Nacogdoches obtaining David Wilson's headright, another man named David Wilson was applying for a headright in Houston. That David Wilson married Ophelia P. Morrell on October 9, 1830 in Vincennes, Indiana. They emigrated to Texas in 1835. They settled in Houston. On February 2, 1838, this David Wilson appeared before the Harrisburg County Board of Land Commissioners in person to claim his head-of-household grant of one league and one labor. His first witness, William Birch, swore that he knew David Wilson and his family when they arrived in Velasco in 1835. Birch further swore that he saw Wilson in Velasco in the spring of 1836 and understood that he was in the army. Wilson's second witness, Daniel Summers, swore that he saw Wilson and his family at Matagorda on November 19, 1835. The copyist of the records had trouble reading the next part of Summers' testimony. He rendered it as "in the same [service?] of the Country," i.e., in the army.9 The Board of Land Commissioners issued Wilson headright certificate number 251.

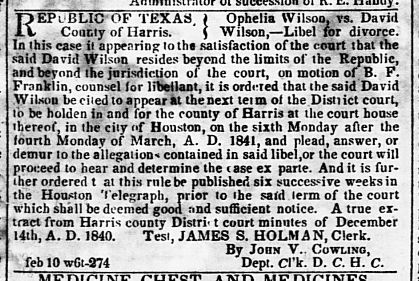

This David Wilson did not proceed with the next step in the grant process, which was to have a survey made. Instead, he abandoned his family, leaving his wife and son for parts unknown. On December 14, 1840, his estranged wife, Ophelia Wilson, filed for divorce. Advertisements posted in the Houston Telegraph and Texas Register gave public notice that a Harris County court would hear Ophelia's divorce filing on May 3, 1841 with or without David.10 The outcome of that case is unknown, but the evidence suggests that David and Ophelia at least remained permanently estranged. As of David's death in 1847 or earlier, he had still done nothing to complete his headright grant.

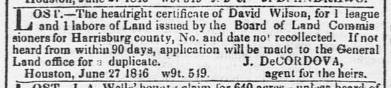

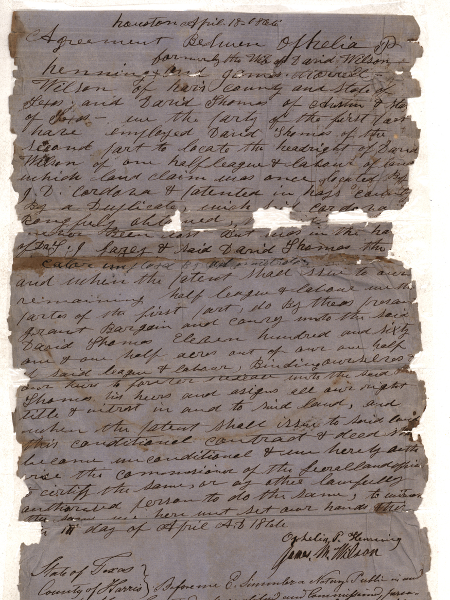

Jacob de Cordova immigrated to Texas in 1839, settling first in Galveston, then Houston. He became one of the largest Texas landowners of his day. Some of his success presumably came from good decisions and hard work, but much of it came by unscrupulous means. One of his known techniques for obtaining large amounts of land at little to no cost was to find Texas Revolution soldiers and immigrants whose heirs never filed for their full benefits and submit applications to become the administrator of their estates without the heirs' knowledge. Wealthy and well connected, De Cordova had contacts in various state and local agencies who alerted him to potential opportunities and abetted his acquisitions. Somehow, in 1846 he learned about David Wilson's neglected land grant. Posing as "agent for the heirs," he filed a request for a duplicate certificate from the General Land Office, claiming that the original certificate issued by the county board was lost. After he received the duplicate certificate, De Cordova swiftly completed the survey and got the grant patented to himself in 1847. There are gaps in the chain of events that happened next that make firm conclusions impossible, but it would seem that after David died, someone determined that Ophelia was his only living heir and forwarded the headright certificate he had possessed since 1838 to her. She then used that certificate to successfully assert her rightful ownership of the land. The GLO file for this grant, Travis 1st-Class 60, is a rarity in that it includes both an original grant certificate issued by a county board and a duplicate certificate that the land office issued to replace a lost original. The only way this makes sense if the original was presented after the duplicate was issued.

Men and women of all classes—not just the wealthy—are susceptible to the sin of greed, and while the politically powerful may have an edge in committing fraud, the potential for it exists whenever someone has something that a dishonest person covets. Perhaps Ophelia got the idea to commit land fraud by seeing how easy it was for Jacob de Cordova to almost get away with it against her. Or, perhaps it came to her naturally, needing no inspiration or instruction from anyone. In either case, she followed De Cordova's method of operations. The same Republic that issued headright grants to immigrants also issued bounty and donation grants to Texas Revolution soldiers. Ophelia's husband's participation in the Revolution was apparently minimal. He may have been eligible for a small bounty grant, but there was no documentation, such as muster rolls or discharge slips, to substantiate such a claim, and he would not have been eligible for the extra benefit paid to a soldier who died in battle, nor was he eligible for a donation grant. On the other hand, there was another David Wilson who was on the Alamo defender rolls, who was due a donation grant and a maximum-size bounty grant, which no one had ever claimed. Perhaps Ophelia had known about him all along, as she and her husband, in their brief time together in Houston, casually conversed about how a man with the same name as his died at the Alamo. If not, she probably learned about him in the 1840s, when sorting out her husband's headright grant with the land office. Perhaps someone at the GLO even pointed out to her that bounty and donation grant applications had not been filed for the other David Wilson. However she learned about it, in 1851, Ophelia Wilson of Houston applied for duplicate bounty and donation grant certificates for David Wilson of Nacogdoches, the fallen Alamo soldier, as his widow. She claimed that the originals had been lost.

The Republic of Texas's original system of using local boards to approve land grant claims became more centralized over time. In 1840, a Republic commissioner of claims was appointed to oversee the process. In 1856, the state of Texas created a Court of Claims to assist the commissioner. The Court of Claims did some due diligence in reviewing Ophelia Wilson's bounty and donation grants. The court confirmed that the David Wilson who died at the Alamo was a different individual from one David J. Wilson from Brooklyn, New York, who served in the Texas army in late 1836. In 1861, it obtained a deposition signed jointly by Ophelia, now living in New Orleans with her new husband, Albert Henning, stating that they were the heirs of "David Wilson, deceased, who lost his life in the Texan War of Independence at the Alamo, in the year 1836." Additionally, A. C. Smith and Hiram May of New Orleans swore that they had known Ophelia Wilson Henning "for the last twenty seven years and that she is the widow of David Wilson deceased who lost his life in the Texan War of Independence at the Alamo in the year one thousand eight hundred and thirty Six."11 The Court of Claims approved Ophelia's claims, which were filed as Milam Bounty 788 and Milam Donation 781.

Anyone who reads the documents in the Texas GLO archives for Travis 1st-Class 60, which Ophelia Henning obtained legitimately, and Milam Bounty 788 and Milam Donation 781, which she obtained by fraud, will recognize that she told two different, conflicting stories and that the David Wilson in the headright grant could not have died at the Alamo, while the David Wilson in the bounty and donation grants could not have been her husband. Henning's two witnesses, A. C. Smith and Hiram May, swore to the effect that they had known her since 1834. Perhaps that part was true; perhaps David and Ophelia Wilson lived in New Orleans for a time during their migration from Indiana to Texas, or perhaps Smith and May knew her from Indiana. How much they actually knew about what happened to David Wilson is unknown. Perhaps they knew he had died and assumed he died in Texas, or perhaps they only knew that Ophelia was now married to another man. They could not have had personal knowledge that her husband died at the Alamo in 1836, because he didn't. Witnesses who gave sworn statements in official proceedings were supposed to state what they knew, not repeat hearsay they were told by the applicant. These two men swore that their statement reflected their personal knowledge. That was a lie.

Smith and May's deposition also stated, "David Wilson was the only child of James and Susan Wilson who were natives of Scotland." The purpose of this statement was to show that David Wilson had no siblings, nephews, or nieces who could claim to be his heirs. Smith and May did not explain how they knew this to be true—did they know his parents? Is that something David told them? Is it something Ophelia told them? The Hennings' deposition did not give any information about Wilson's family, other than to say Ophelia was his only heir.

Historical Assessment

Given the clear, irrefutable evidence in the land grant files that the David Wilson who was married to Ophelia Wilson was alive in 1838, lived in Houston, and did not die in the Alamo, how did we get to the current state of affairs, where everything in this Alamo defender's biography is wrong? The first person to blame is Amelia Williams, a Ph.D. student at the University of Texas who wrote her doctoral dissertation, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of Its Defenders," in 1931. About half of this 500-page thesis focuses on identifying the men who fought at the Alamo, those who left during the siege, the women and children who survived, etc. Very much like Bill Groneman's Alamo Defenders, "A Critical Study" contains short biographies on each Alamo defender giving his full name, age, place of origin, and other details. The main thing that distinguishes "A Critical Study" from Alamo Defenders is that the latter book is intended for a general audience, while "A Critical Study" is meant to be an academic study, heavy on analysis, citations, and footnotes, versus on just telling the story. A trimmed-down, edited version of Williams's "A Critical Study" was published as a series in four issues of the Southwestern Historical Quarterly in 1933 and 1934. Her "Annotated List of Defenders," which is her most lasting legacy, was published in April 1934.

Any historian who tries to use Williams's "A Critical Study" for Alamo research is immediately confronted by how bad it is. Williams provides multiple citations to go with each Alamo defender biography, but many of them are to non-existent documents, or documents that do not pertain in any way to the person whose biography they are cited in or, for that matter, to anyone at the Alamo. She may give three or four citations that are actually just multiple instances of the same source. A great deal of information Williams provides is unsourced, and a great many of her citations do not support her assertions in any way. She misquotes her sources. Her typescripts of handwritten documents and other sources contain glaring errors on nearly every line. For example, her "Exact Copy of the Roll on the Alamo Monument"—her attempt to duplicate a list of 186 names— has 42 mistakes, including 9 complete omissions. Her conclusions are baffling and illogical. While there is some good information in "A Critical Study," it is mostly rubbish. Her biography of David Wilson is no more or less flawed than any of her other biographies. It reads:

WILSON, DAVID L: Age, 29; rank, private; native of Scotland, resident of Nacogdoches. Sources: Milam, 781, 788; Nacogdoches, 662, 640, 641; I Robertson, 413; Muster Rolls, pp. 2, 29; Telegraph and Texas Register, March 24, 1836; Court of Claims Vouchers, No. 893, File (S-Z). This man's widow married Albert Henning. She acted as administrator of his estate.12

Here is how each of the ten sources Williams cited contributed to this biography:

- Milam Donation 781 - this file contains the two depositions—the first by Ophelia and Albert Henning and the second by A. C. Smith and Hiram May—which claim that Ophelia Henning was the widow of David Wilson who died at the Alamo in 1836. It also contains the statement, "David Wilson was the only child of James and Susan Wilson who were natives of Scotland."

- Milam Bounty 788 - this file has the duplicate certificate issued in 1851 approving 1920 acres to the heirs of David Wilson for his having "fallen with Travis in the Alamo." It includes remarks about the survey made by Ophelia Henning of New Orleans, formerly Ophelia Wilson.

- Nacogdoches Donation 662 - this file contains a duplicate certificate to replace a donation certificate originally issued to the heirs of David Wilson in 1857. The recipient of the duplicate certificate, and the person who completed the grant, was Samuel D. Gibbs. Nowhere in this 51-page file is the Alamo, the Texas Revolution, or Ophelia Wilson Henning mentioned, and it contains no information about David Wilson. There is no reason to believe this grant is relevant to the Alamo defender.

- Nacogdoches Bounty 640 - this file contains a duplicate certificate to replace a bounty certificate originally issued to the heirs of David Wilson in 1862. The duplicate was issued in 1869. Its recipient is not named. There is no reason to believe this grant is relevant to the Alamo defender.

- "Nacogdoches 641" - this document is non-existent. There is another Nacogdoches grant, Nacogdoches Bounty 678, which is apparently related to the above two. Like them, there no reason to believe it is relevant to the Alamo defender.

- Robertson 1st-Class 413 - this is the single-man's headright grant obtained by George Pollitt in 1838. It states that he appeared before the Nacogdoches Board of Land Commissioners and proved that "the L David Wilson"—meaning, "the late David Wilson"—arrived in Texas previous to May 2, 1835, died in 1836, and was a single man. Williams's misunderstanding of the meaning of "the L David Wilson" is apparently where she got the middle initial, L., for the name "David L. Wilson" is not found in any document pertaining to him or anyone else in the General Land Office's land grant archives. To put it simply, Amelia Williams made the name "David L. Wilson" up.

- Muster Roll 2 - this is GLO's Alamo casualty list, which reads "David Wilson, Private, Nacogdoches."

- Muster Roll 29 - this is a muster roll from the Battle of San Jacinto. It has nothing to do with the Alamo and does not contain a soldier named Wilson.

- Telegraph and Texas Register, 3/24/1836 - this is the Telegraph casualty list, which includes "David Wilson, Nacogdoches" among the privates.

- Court of Claims 893 - this is the Court of Claims' inquiry into Ophelia Wilson's bounty and donation grant claims.13 It shows that David J. Wilson of Brooklyn, New York fought in the Texas Revolution and then went back to Brooklyn, where he died. It contains no information about Ophelia Wilson or her husband and no information about the fallen Alamo defender.

To summarize, of the ten sources Williams cites, one does not exist (#5). One exists but has nothing to do with anything (#8). Four give no information except that David Wilson was from Nacogdoches (#3, #4, #7, #9), and only two of those appear to have been about the Alamo defender (#7, #9). One source was definitely not about the Alamo defender (#10). Out of the three sources that are left, one shows that a David Wilson of Nacogdoches who died in 1836 was single (#6). That document was Williams's only source for the name David L. Wilson, even though that name does not appear in it. Two state that the Alamo defender's widow was Ophelia Henning (#1, #2). This claim is disproven by Travis 1st-Class 60, which Williams does not cite. None of Williams's sources say anything about Wilson's origin except that his parents were Scottish. None give his age or year of birth.

The next several generations of historians who came after Williams focused mostly on whether her Alamo defenders list has the correct people on it (which it doesn't). They did not go into details of their biographies, such as middle initials, ages, families, and places of origin. Since there never has been any question that a David Wilson died at the Alamo, historians had no interest in either verifying or challenging the biographical claims Williams made about him, as long as his name was on her list. In that respect, Bill Groneman was a different kind of historian. "The people who were caught up in the battle of the Alamo were more than simply names on a list," Groneman writes in the preface to Alamo Defenders. "To add a background, a description, or a human face to some of these names will, it is hoped, help in the appreciation of the Alamo as a human tragedy and a national event."14

Groneman's premise was great, but he made a serious mistake: he used the biographies Amelia Williams wrote in "A Critical Study" as his starting point. Nearly every Alamo defender biography in Alamo Defenders is a Groneman edit or rewrite of Williams's extremely flawed research. When we compare Groneman's biography of David Wilson with Williams's, we see only two differences: Groneman included Wilson's parents' names— that is, the parents of David Wilson of Houston, not the Alamo defender—and he added that Wilson "may have been one of the volunteers who accompanied Philip Dimitt to Bexar and the Alamo." He preserves all of Williams's mistakes: the made-up middle initial, the made-up age, the claim that he was born in Scotland, and the claim that Ophelia Henning was his wife.

Groneman's assertion that Wilson may have gone to Bexar with Captain Dimitt is based on a document that has not been discussed yet: the so-called "Goliad Declaration of Independence." On December 20, 1835, the population of Goliad issued a statement declaring Texas' independence from Mexico. This controversial pronouncement was not ratified by the provisional government. Independence did not officially become the goal of the Texas Revolution until March 2, 1836. Philip Dimitt, who is among the document's 91 signers, was the captain of the Texian volunteers at Goliad and was a strong supporter of the declaration. His hardcore advocacy for Texas independence alienated him from other political and military leaders who were more cautious or indecisive. He resigned his command at Goliad in protest in January and subsequently went to Bexar. Groneman supposes that because one of the Goliad declaration's signers was named David Wilson, the David Wilson who died at the Alamo may have accompanied Dimitt to Bexar. There are two reasons why this supposition is weak. First, the evidence has shown that there were several men in Texas named David Wilson during the Texas Revolution. Ophelia Wilson's husband was seen at Matagorda on November 19, 1835 and was said to have been in the army at that time. The Texian garrison at Goliad included a company of soldiers who had come from Matagorda in October, and overall, there was more travel and communication between Goliad and Matagorda than there was between Goliad and Nacogdoches. If one had to assume, it would make more sense to assume that the Goliad declaration signer was Ophelia's husband, not the Alamo defender.15 Furthermore, while Dimitt did go to Bexar after resigning, there is no evidence that he brought a company of soldiers with him.16 If David Wilson did go from Goliad to Bexar, he probably went with James Bowie, not Philip Dimitt. Even then, that is a supposition, not a conclusion, and it does not belong in a brief biography of Wilson because we do not even know whether he and the Goliad declaration signer were the same person.

While there have been many books written about the Alamo since Alamo Defenders, surprisingly little original research has been done on the biographies of Alamo personnel. There have been some biographies written about specific men who died at the Alamo, either because the subject was a famous historical figure, such as David Crockett, or because the writer had a particular interest in the subject, usually because the writer was related to him. There has not been a comprehensive compilation of Alamo defender biographies since Alamo Defenders. As a result, the biographies some of the defenders such as David Wilson, who was not famous and whose lineage is utterly undocumented, have not been updated since 1990.

One of the more significant Alamo authors since Groneman is Thomas Ricks Lindley. His book, Alamo Traces (2003), is not entirely about Alamo personnel biographies, but he does give them considerable attention, and he devotes an entire chapter to criticizing Williams. "Time and space does not allow for a litany of every error, probable fabrication, and unfounded conclusion thus far discovered by this writer," Lindley writes.17 In exposing Williams's historical malpractice, Lindley told a truth out loud that had been a dirty secret among Alamo historians for decades, and for that, he deserves applause. Many of the corrections he made to Williams's biographies are spot on and should have been made a half-century earlier.

Unfortunately, Lindley's own particular agendas about the Alamo often get in the way of his findings, and David Wilson is a case in point. Lindley's big problem with Wilson was that one of the witnesses in George Pollitt's hearing before the Nacogdoches County Board of Land Commissioners in 1838 was Lewis Rose. If that name sounds familiar to you, yes, it is that Lewis Rose: the man, also known as Moses Rose, who claimed that on March 3, 1836, Colonel Travis drew a line in the sand and challenged his men to either cross the line and stay with him in a fight to the death, or to attempt to escape from the Alamo and possibly save his life. To Lindley, everything Rose said was a lie—not just everything he said about Travis's line in the sand and his escape from the Alamo, but everything about everything. That means that if Rose said David Wilson of Nacogdoches died at the Alamo, then he did not really die at the Alamo. Lindley's theory is that the Alamo defender named David Wilson, if there even was one, was the man who signed the Goliad Declaration of Independence, who "most likely entered the Alamo with James Bowie."18 Where was he from? Lindley does not know, does not offer any ideas, and does not seem to care. He only knows that he could not have been from Nacogdoches, because that would mean Rose told the truth about something. As for the Telegraph's announcement of a fallen Alamo defender named David Wilson from Nacogdoches, "the newspaper list might have been wrong about Wilson's origin," Lindley asserts. It is one thing, when two sources disagree, to choose one over the other; to evaluate them and conclude which one is wrong and which one is right. It is something else, though, to do as Lindley does here, which is to declare that two sources that agree with each other are both wrong, without making any sort of case for what the issue is. For that reason, Lindley's theories about David Wilson cannot be taken seriously. "One thing, however, is certain," he adds, though. "If a man named David Wilson died at the Alamo, he was not the husband of Ophelia P. Wilson."

Conclusion

There was a man named David Wilson who died in the Battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836. The man who the Alamo honors and whose biography is in the Handbook of Texas, in dozens of history books, and on hundreds of web sites, is not the man who gave his life for Texas independence. Even the details given about that other man—his middle initial, his age, his place of origin—are wrong. These errors were born of fraud, memorialized and multiplied in 1931 by one very bad historian, and republished by a very influential historian in 1990. The purpose of this article is not just to correct the record about David Wilson, but to show that anyone doing research on Alamo personnel must be extra cautious when quoting the conclusions of others, no matter how reputable the source seems to be. The problems with David Wilson that this article highlights are not an anomaly in Alamo defender biographies; they are the norm. Take any random Alamo defender biography found on thealamo.org, the Handbook of Texas, Wikipedia, or anywhere else, and it is probably going to be written or heavily influenced by Bill Groneman, whose work was heavily influenced by Amelia Williams, who usually got more things wrong than she got right. Researchers must take the extra time to follow the citations and examine the source documents for themselves.

1"Wilson, David L.", The Alamo, accessed on 6/27/20025.

2Historians disagree on whether Dimitt's surname was spelled with one m or two. TexasCounties.net's standard is to spell his name the way he signed it, which is Dimitt, with one m. When we are quoting from a document or authority that uses another spelling, we use the quoted author's spelling.

3Groneman, Bill, "David L. Wilson", The Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed on 6/27/2025.

4Groneman, Alamo Defenders, p. 121.

5Literally, the law entitled "All persons (Africans, the descendants of Africans, and Indians excepted)." It was understood that the benefit only applied to men.

6Blake, vol. 27, pp. 70-72.

7The reason for the Nacogdoches County Board of Land Commissioners' consistent use of May 2, 1835 in evaluating headright claims eludes this researcher. The Texas headright law required applicants for first-class headrights to have immigrated prior to March 2, 1836. Applicants who immigrated after that date could apply for smaller second-class or third-class headrights. May 2, 1835 had no significance in the headright law. Technically, Pollitt and his witnesses should have proven that Wilson was at least 17 years old when he immigrated, but the Nacogdoches land commissioners apparently overlooked this requirement, as did their counterparts in many other counties, for the testimonies often lacked this information.

8Blake, vol. 27, pp. 70-72.

9White, p. 39.

10Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston), 2/10/1841, p. 3.

11Milam Donation 781.

12Williams, p. 285.

13This document is now filed in the GLO archives as Court of Claims 8880.

14Groneman, p. xii.

15Document AU-588 in the Republic Claims data base shows that a David Wilson served in Captain William S. Fisher's company at Dimitt's Point, which was between Matagorda and Goliad, from June to September 1836. This could be the same man as Ophelia Wilson's husband and the Goliad declaration signer, or they could all be different.

16The assertion that Dimitt brought a company of "about thirty" men to reinforce the Alamo has been made by Groneman and others many times, but they have never cited any documentary evidence for it. A letter written by Dimitt hints that he brought his lieutenant, Benjamin F. Nobles, with him, but it does not mention anyone else. The evidence against Dimitt bringing a group of any significant size is that none of the letters or memoirs written by Texian officers, soldiers, or any other witnesses in Bexar mention his arrival, and our knowledge about the number of men who were killed at the Alamo, and how they arrived there, simply does not allow for an extra thirty men from Goliad.

17Lindley, p. 42

18Lindley, p. 223.

- Blake, Robert Bruce, Research collection.

- Democratic Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston), 7/1/1846.

- General Land Office, Certificate of Character SC 70:63.

- General Land Office, Robertson 1st-Class 413.

- General Land Office, Travis 1st-Class 60.

- General Land Office, Court of Claims file 8880.

- General Land Office, Milam Bounty 788.

- General Land Office, Milam Donation 781.

- Groneman, Bill, "David L. Wilson", The Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association, accessed on 6/27/2025.

- Groneman, Bill, Alamo Defenders, Eakin Press, 1990.

- Jenkins, John H., editor, Papers of the Texas Revolution, Presidial Press, 1973, vol. 4, doc. 1561, Goliad declaration of independence, 12/20/1835.

- Lindley, Thomas Ricks, Alamo Traces, Republic of Texas Press, 2003.

- Telegraph and Texas Register (Houston), 2/10/1841.

- White, Gifford E. (typist), Board of Land Commissioners Harris County, vol. 1, 1980.

- Williams, Amelia, "A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of Its Defenders," Southwestern Historical Quarterly, April 1934.

- "Wilson, David L.", The Alamo, accessed on 6/27/20025.